Last year, I was honoured to interview the Queen of Cyberpunk herself, Pat Cadigan, at FantasyCon. During the course of the interview, she recounted an anecdote about a reader who told her she wanted to read Synners. While the book was one of the seminal founding-blocks of the cyberpunk genre, Cadigan warned this young reader that there wasn’t actually all that much fiction in the book’s science fiction… anymore. Her comments got me thinking – how much fiction is required to make it science fiction? How fictional does the science involved need to be? How scientific?

Future science

Most science fiction deals with ideas of the technological and scientific advancements we might make in the future (unless you’re George Lucas and confuse everyone with ‘A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…’). For instance, mobile phones were not ‘a thing’ back when the crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise were flipping open their communicators. The fact that we have now developed the technology to remotely communicate with each other does not make Star Trek: The Original Series any less science fiction. It was science fiction then and it is now.

Most science fiction deals with ideas of the technological and scientific advancements we might make in the future (unless you’re George Lucas and confuse everyone with ‘A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…’). For instance, mobile phones were not ‘a thing’ back when the crew of the U.S.S. Enterprise were flipping open their communicators. The fact that we have now developed the technology to remotely communicate with each other does not make Star Trek: The Original Series any less science fiction. It was science fiction then and it is now.

But what if communicators, tricorders, interstellar travel, and more were real at the time of the show’s production? Would these elements change its genre classification? Black Mirror has made its name extrapolating only slightly further ahead of where we are currently, and taking those extrapolations to terrifying (though often scarily realistic) places. As long as the implementation of the ‘science’ in question has some elements of futurism or ‘what if?’, the stories still fall firmly into the realms of science fiction.

Real science

Does the science in science fiction need to be realistic? When Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar was released, there was a lot of talk about the science behind the narrative. Great care was taken to have everything in the film be theoretically possible (even when it meant the director saying ‘I want to do X’ and the scientists having to make something up). But did the realistic element of the science make any real difference to the narrative? Did you care more about the characters or story of Interstellar than you did with science fiction stories with utterly ridiculous ‘science’ behind them?

Andy Weir writes science fiction based heavily on what is possible. His debut novel, The Martian, follows an astronaut who has to deal with being abandoned on Mars. All of the work Watney does to survive is based in real science. Weir uses a similar idea in his follow-up, Artemis. The lunar base works off current theories of how we could set up a colony on the moon. Not that the idea of using scientific theory of extra-planetary life is new. Robert Heinlein did something similar with The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, especially with his exploration of the toll living with less-gravity would take on one’s body (something that has actually been picked up by a lot of mainstream science fiction).

Andy Weir writes science fiction based heavily on what is possible. His debut novel, The Martian, follows an astronaut who has to deal with being abandoned on Mars. All of the work Watney does to survive is based in real science. Weir uses a similar idea in his follow-up, Artemis. The lunar base works off current theories of how we could set up a colony on the moon. Not that the idea of using scientific theory of extra-planetary life is new. Robert Heinlein did something similar with The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, especially with his exploration of the toll living with less-gravity would take on one’s body (something that has actually been picked up by a lot of mainstream science fiction).

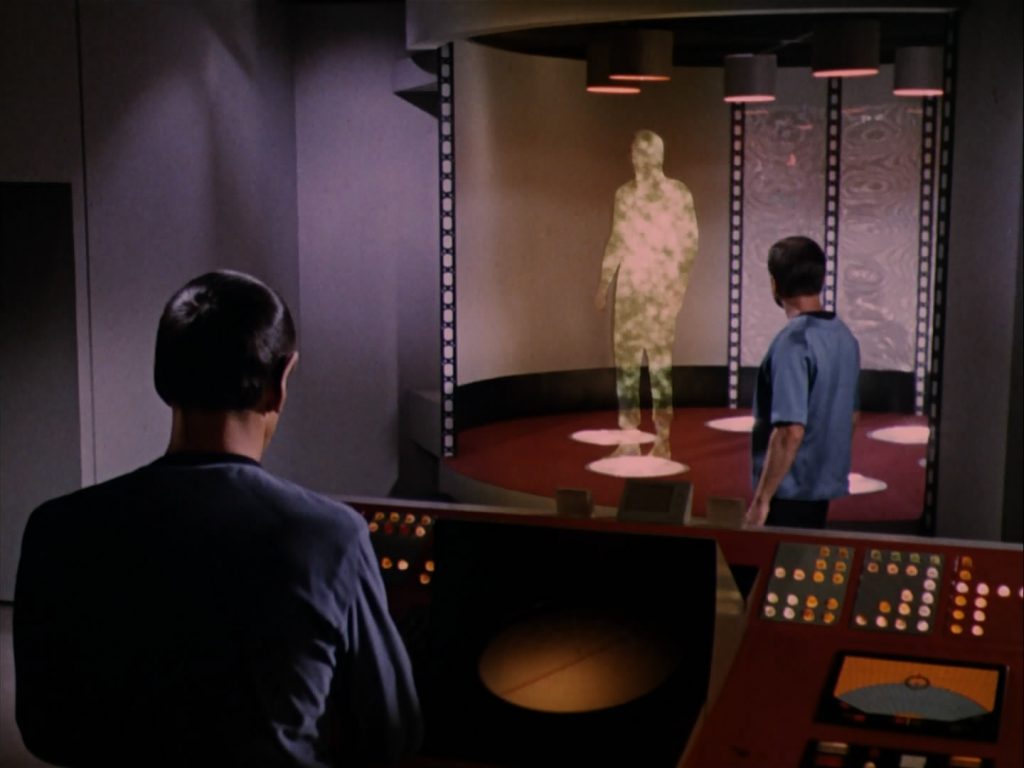

I’m a fan of the stupid ‘science’ of a lot of science fiction. The transporter makes no sense as a real scientific concept once you break it down – who would want to destroy themselves and create a new copy at their destination?! But it had genuine importance from a production standpoint (they couldn’t afford a shuttle, so this was a quick and easy way to get the crew from the ship to a planet). Similarly, most science fiction ignores relativity in faster than light travel. This makes for more interesting stories, where characters can travel across vast areas of space quickly and remain in the same relative time as everyone else around them. Sometimes ‘real’ science can hinder the fiction.

There’s no quota for how much science is in your science fiction, or even how fictional your science is. At the end of the day, as long as it’s a good story… who cares!

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe