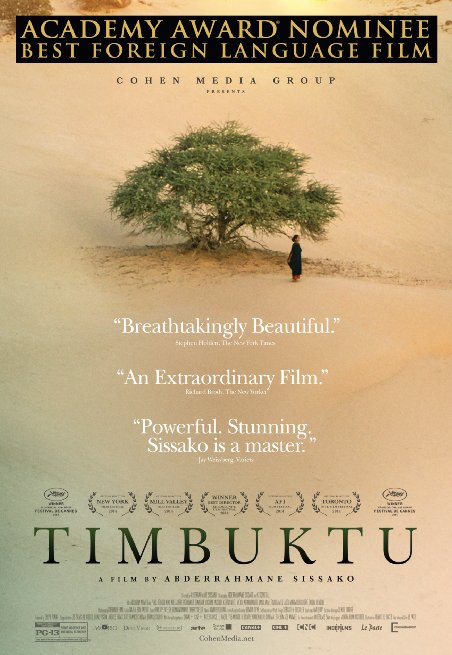

Timbuktu tells the story of a community living under the oppression of jihadi forces in the eponymous city in Mali. It takes a largely ensemble approach, following various plot strands in the lives of both the Islamist police and the civilians. This film has toured around various festivals where it has built a strong reputation and has had scattergun general release internationally. Having waited to see this for some time, I was not disappointed.

Having gone in with some preconceptions, I was surprised by Timbuktu. I was expecting a dour collage about a community fracturing with oppression and frustration – something along the lines of Matteo Garrone’s Italian criminal community anthology Gomorrah. It is quite a different entity though.

Having gone in with some preconceptions, I was surprised by Timbuktu. I was expecting a dour collage about a community fracturing with oppression and frustration – something along the lines of Matteo Garrone’s Italian criminal community anthology Gomorrah. It is quite a different entity though.

The biggest surprise for me was the strong element of humour

It might have a diffuse set of plots and incidents but most of them circle a main thread about the cattle herd Kidane living in the desert outside of the city who is eventually dragged into the oppressive regime he has sought to avoid. The film contrasts the initial idyll of his family’s life in their desert tents with the harassment and cruelty taking place in Timbuktu and then sets up the inevitable collision.

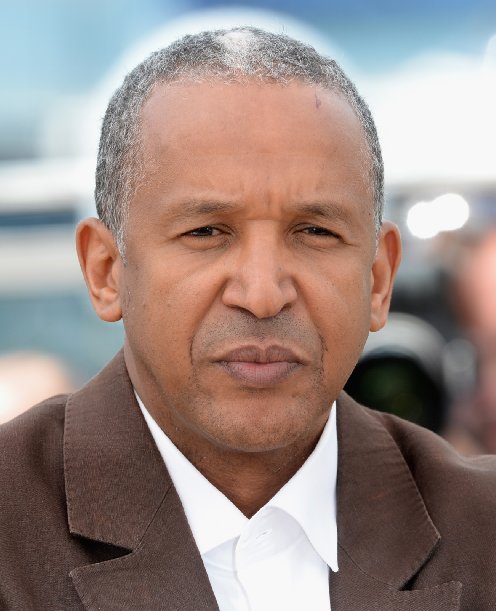

Perhaps the biggest surprise for me was the strong element of humour. The laws the jihadis enforce are patently ridiculous and director Abderrahmane Sissako finds this an ample source of mockery. Much is done with the simple administrative absurdity of imposing this repressive regime in the region. Many of the jihadis are called out on their atrocious attempts to speak Arabic, and the authority they seek is undermined by their constant need to filter dictates through several translators into local languages or French.

Vignettes of violence may be brief and sparing but their threat is hanging over the drama

Then there are the brilliant little acts of rebellion the locals organise. The best is the inventive method the youth adopt when football is banned – playing fully synchronised with an imaginary ball on a dusty pitch. Absurd, defiant and wonderful. This is compounded by the naked hypocrisy of the oppressors too. The men policing the football ban are at one point found arguing over their favourite teams and France’s performance in the World Cup. Music, cigarettes and sexual ‘impropriety’ are banned but we see Islamists variously expressing love of rap music, puffing or leching.

The humour does not, however, detract from the cruelty and suffering on display in the film. We are invited to laugh at the nonsense the Islamist police spew out but there is no question as to how horrible their regime is. Vignettes of violence may be brief and sparing but their threat is hanging over the drama throughout, and the film only restrains itself for so long. Things build steadily: a woman is reduced to tears and impotently wishes to leave after she is harassed out of selling fish; musicians and people disobeying the dress code are arrested; one boy is picked up for possessing a football. Eventually we see how they are punished. Perhaps one of the most awful scenes is simply of a young woman crying on a bed after she has been forced to marry a jihadi – sexual violence being the wretched implication.

Nor is this a film that skips over the distinctions between Islam and Islamism

I should stress this does not engage in demonisation. On the Islamist side, we see members being confused by and contradicting the cause they have joined. It doesn’t mean they aren’t culpable and it does not diminish their cruelty but we see a group of vicious, stupid, entitled, deluded, and sometimes conflicted people rather than inconceivable monsters. Nor is this a film that skips over the distinctions between Islam and Islamism. The faith of the civilians is not grounds for submission but the last tether on which some of them hang their dignity and which allows them to implement some sort of defiance. The Imam has several scenes where he delicately confronts the leader of jihadis in an effort to defend his community and disarm the jihadis of their rhetoric.

Timbuktu is not always an easy watch but it does not exploit its subject for gratuitous violence – Sissako uses ample restraint and when brutality is depicted it is contextualised and exhibited with a purpose. I think the best achievement here is showing a life that includes humour and dignity in spite of living under a regime determined to despoil and humiliate. Timbuktu well deserves its plaudits and reputation.

Verdict: I left Timbuktu feeling galvanised and indignant. Do go and see it if you can.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe