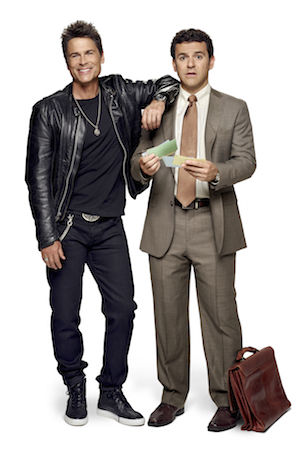

Watching – and thoroughly enjoying – The Grinder has prompted me to think about sitcoms and their use of ‘gimmicks’ as both a set-up for an entire series as well as for singular jokes. The Grinder is built around the gimmick of lampooning tropes of TV lawyers as well as scripted television more generally. It will take a particular trope of (bad) TV legal dramas and build out the episode’s narrative from there, usually opening with a scene from the fictional TV series (within the TV series) as an example. I get a kick out of the show, probably a result of all those years watching David E. Kelly shows (Ally McBeal, The Practice, Boston Legal), but I admit I’m worried about where the show will go from here. Won’t they run out of tropes to lampoon soon? How could this kind of gimmicky set-up possibly have any real staying power?

Then again, sitcoms themselves are always somewhat gimmicky and often face problems with becoming stale as the episodes and seasons drag on. Sitcoms, as a genre, center around a singular premise that encourages a circular format – change introduced for the course of an episode (or at most a few) that ultimately resolves and resets the ‘situation’. How could they not get old with a template the requires they always return to the status quo? Without change, finding new and interesting storylines can be extremely difficult. However, the lasting popularity of the sitcom formula suggests that a gimmicky set-up for comedy might just be sustainable for the long term.

The subgenres of sitcoms and their gimmick staples

Sitcoms have been around for a long time, first on radio before making the jump to television. I Love Lucy (1951-1957) is one of the earliest sitcoms and established the three-camera set-up that is still widely used today. The show followed husband and wife (in the show and real life) of Lucy and Ricky (Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz) and the zany antics Lucy would get up to in order to find a way into Ricky’s entertainment act. Many of the tropes we see in today’s sitcoms first appeared in I Love Lucy.

Under the heading of sitcom, a number of subgenres have been identified, boiling down to these tropes:

- Tortuous marriages

- General home life

- Cultural differences and specific comedy

- Fantastical settings

- For and starring children

- An unsuited pair – in either a platonic or romantic relationship

- Roommates/house shares

- The work environment

From the very beginning, many of these subgenres have worked together in the one series. For instance, in I Love Lucy is both a domestic sitcom (based in Lucy and Ricky’s home) as well as a work sitcom (with Lucy’s end goal usually involving Ricky’s act). The Grinder has continued this combination approach, by appropriating tropes from three subgenres: the odd couple, domestic, and work sitcoms.

From the very beginning, many of these subgenres have worked together in the one series. For instance, in I Love Lucy is both a domestic sitcom (based in Lucy and Ricky’s home) as well as a work sitcom (with Lucy’s end goal usually involving Ricky’s act). The Grinder has continued this combination approach, by appropriating tropes from three subgenres: the odd couple, domestic, and work sitcoms.

While the standard sitcom set-up and its subgenres don’t necessarily require gimmicks in the format, they do often appear. When I talk about sitcoms using gimmicks I mean something above and beyond just the premise of the show (usually). Instead, it is more about how episode narratives a built outside of the core set-up. A ‘gimmick’ is defined as: ‘an ingenious or novel device, scheme, or stratagem, especially one designed to attract attention or increase appeal.’ This is how sitcoms use them, to widen appeal with a unique device for comedy.

When it worked

Over the years, there have been some truly brilliant sitcoms, from M*A*S*H to Cheers, Seinfeld to The Golden Girls,The Vicar of Dibley to Parks and Recreation. Many of these did not rely on gimmicks for appeal or extra laughs, though some did. Take The Vicar of Dibley and its famous joke sequence at the end of every episode or Home Improvement’s use of neighbor Wilson, who liked to drop a bit of wisdom on the Taylor family while only ever showing the top half of his face from the other side of the fence. Kids TV has used it as well: Lizzy McGuire included animated versions of Lizzie appearing to provide emotional soliloquies for angsty middle school viewers. Even the more popular pseudo-documentarian style of shows like The Office, Modern Family, and Parks and Recreation could be considered a gimmicky set-up.

Over the years, there have been some truly brilliant sitcoms, from M*A*S*H to Cheers, Seinfeld to The Golden Girls,The Vicar of Dibley to Parks and Recreation. Many of these did not rely on gimmicks for appeal or extra laughs, though some did. Take The Vicar of Dibley and its famous joke sequence at the end of every episode or Home Improvement’s use of neighbor Wilson, who liked to drop a bit of wisdom on the Taylor family while only ever showing the top half of his face from the other side of the fence. Kids TV has used it as well: Lizzy McGuire included animated versions of Lizzie appearing to provide emotional soliloquies for angsty middle school viewers. Even the more popular pseudo-documentarian style of shows like The Office, Modern Family, and Parks and Recreation could be considered a gimmicky set-up.

One of my favourite sitcoms of the early 2000’s is the BBC’s Coupling. The show was a kind of British Friends with the innuendo factor turned up to 11. But re-watching the show recently, I realized it is quite gimmicky in the way it sets up the main joke of the episode. Jeff (the wonderful Richard Coyle, whose departure after 3rd season left a gaping hole) comes up with a bizarre theory of social interaction which he shares with Steve (Jack Davenport) and Patrick (Ben Miles) over beers at the local bar. This will often prompt divergent plots within the episode to derail in ridiculous and hilarious ways, a kind of inception version of sitcom humour.

One of my favourite sitcoms of the early 2000’s is the BBC’s Coupling. The show was a kind of British Friends with the innuendo factor turned up to 11. But re-watching the show recently, I realized it is quite gimmicky in the way it sets up the main joke of the episode. Jeff (the wonderful Richard Coyle, whose departure after 3rd season left a gaping hole) comes up with a bizarre theory of social interaction which he shares with Steve (Jack Davenport) and Patrick (Ben Miles) over beers at the local bar. This will often prompt divergent plots within the episode to derail in ridiculous and hilarious ways, a kind of inception version of sitcom humour.

Using tropes as a way to generate comedy is not something new – or unique – to The Grinder. It’s long been a staple of great humour in sitcoms, a fad that has only increased in popularity since the turn of the century. Back in 1999, Simon Pegg and Edgar Wright formed the beginning of a wonderful friendship with their series Spaced. The series made so many pop culture references through its episodes, the DVD release included an onscreen ‘Homage-o-meter’ as a special feature. For fans of films (particularly SF ad horror), comics, and video games, the show allowed us to revel in all our geeky loves. With meta-humour becoming all the rage, the US jumped on the bandwagon with Dan Harmon’s fan favourite, Community. Entire episodes of Community are structured around genre tropes, showing how ridiculously constructed they all are.

When it didn’t work – being penned in by the gimmick

With How I Met Your Mother, we were robbed of any real payoff for the series premise of recounting the story of a meet-cute to the product (children) of said union. And yet that isn’t really what the series is about at all. Instead, it becomes the tale of a will they/won’t they relationship. The titular ‘mother’ is an afterthought. When she does finally appear, she is the epitome of every stereotypical ‘perfect’ (aka unbelievably bland) screen woman. And if it weren’t bad enough to have her be utterly plastic and unoriginal, almost as soon as she’s introduced she is killed off. So what was the point of setting the premise up that way, just to give the audience certain expectations only to pull the rug out from underneath us? It was quite refreshing when I thought Ted and Robin would not end up together. But a set-up that had potential to throw a romcom type sitcom on its head was thrown out the window in favour of something far more ordinary and predictable.

With How I Met Your Mother, we were robbed of any real payoff for the series premise of recounting the story of a meet-cute to the product (children) of said union. And yet that isn’t really what the series is about at all. Instead, it becomes the tale of a will they/won’t they relationship. The titular ‘mother’ is an afterthought. When she does finally appear, she is the epitome of every stereotypical ‘perfect’ (aka unbelievably bland) screen woman. And if it weren’t bad enough to have her be utterly plastic and unoriginal, almost as soon as she’s introduced she is killed off. So what was the point of setting the premise up that way, just to give the audience certain expectations only to pull the rug out from underneath us? It was quite refreshing when I thought Ted and Robin would not end up together. But a set-up that had potential to throw a romcom type sitcom on its head was thrown out the window in favour of something far more ordinary and predictable.

Other sitcoms have found interesting gimmicks increase their initial appeal while necessarily limiting the story. The biggest example of this recently is The Last Man on Earth. Rather than sticking with the premise – which would have gotten old very quickly, the show turned into a fairly standard sitcom with a few close-knit neighbours navigating romantic perils. Only, they happened to be in a post-apocalyptic setting. Gimmicks in a sitcom’s premise can often put undue limitations on the possible storylines. Take Samantha Who – a sitcom based on the premise that a mean woman suffers amnesia and develops a different personality. Most of the comedy is thus born out of the incongruousness of her before and after life. But when she either settles into one or the other, where can that comedy go? With 2 Broke Girls, they will never be able to save enough money to get what they want, or the series would be over. Therefore, the writers are limited in that the girls can never be truly successful, while the viewer thinks ‘Why would anyone give them a business even if they do ever save enough money, they’re clearly bloody terrible at using their income responsibly.’ (I mean, come on, they are ‘broke’ but still have a horse. What?!)

Other sitcoms have found interesting gimmicks increase their initial appeal while necessarily limiting the story. The biggest example of this recently is The Last Man on Earth. Rather than sticking with the premise – which would have gotten old very quickly, the show turned into a fairly standard sitcom with a few close-knit neighbours navigating romantic perils. Only, they happened to be in a post-apocalyptic setting. Gimmicks in a sitcom’s premise can often put undue limitations on the possible storylines. Take Samantha Who – a sitcom based on the premise that a mean woman suffers amnesia and develops a different personality. Most of the comedy is thus born out of the incongruousness of her before and after life. But when she either settles into one or the other, where can that comedy go? With 2 Broke Girls, they will never be able to save enough money to get what they want, or the series would be over. Therefore, the writers are limited in that the girls can never be truly successful, while the viewer thinks ‘Why would anyone give them a business even if they do ever save enough money, they’re clearly bloody terrible at using their income responsibly.’ (I mean, come on, they are ‘broke’ but still have a horse. What?!)

Gimmicks and a circular format = staleness

Some series try to combat this staleness by introducing gimmicks part way through… Archer, for instance, changed up the entire premise for its fifth season, giving us Archer: Vice. From international spies to running a drug cartel, the show took the same characters and put them in a very different situation. The result? Disappointing.

Some series try to combat this staleness by introducing gimmicks part way through… Archer, for instance, changed up the entire premise for its fifth season, giving us Archer: Vice. From international spies to running a drug cartel, the show took the same characters and put them in a very different situation. The result? Disappointing.

While sitcoms and the gimmicks they employ are brilliant ways to create comedy, they come with expiration dates – ones that shows tend to ignore, continuing to run well after the premise has grown stale. The constant popularity of the genre, however, suggests that this set-up is a solid one, but that all sitcoms need to have an end-point in sight and stick to it. Trying to hold on beyond the limitations of the gimmicks they prescribe to only tarnishes what could have been remembered as a brilliant series that knew when to bow out.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe