An aged lord reflects on the legacy of his kingdom. He resolves to divide his realm between his three children expecting them to act harmoniously. Despite the protestations of his youngest that this is grossly unwise, the lord proceeds to sunder his realm. The storm of madness, vengeance, and bloodshed that follows can only be described as ‘chaos’. For that is the name of this tale: Ran. The last of the great samurai epics by Akira Kurosawa, its name means variously ‘anarchy’, ‘rebellion’, ‘revolt’, ‘confusion’, ‘disturbed’ and ‘chaos’.

Canny readers will, of course, recognise the plot from another source. This film is King Lear relocated to Japan in the Warring States period. The idea came from a kernel of historical legend. The tale goes that daimyo Mori Motonari admonished his sons with a demonstration of arrows, taking one and breaking it in two. He then took three and showed that they held together, the bundle could not be broken. His message was that they would be stronger together, but would surely be broken if they acted apart in an era of vicious warfare. Kurosawa took this seed and mapped out an alternate story based on the simple premise taken from King Lear: what if that lord’s children had been petty and self-interested?

Canny readers will, of course, recognise the plot from another source. This film is King Lear relocated to Japan in the Warring States period. The idea came from a kernel of historical legend. The tale goes that daimyo Mori Motonari admonished his sons with a demonstration of arrows, taking one and breaking it in two. He then took three and showed that they held together, the bundle could not be broken. His message was that they would be stronger together, but would surely be broken if they acted apart in an era of vicious warfare. Kurosawa took this seed and mapped out an alternate story based on the simple premise taken from King Lear: what if that lord’s children had been petty and self-interested?

The film that ensues is an interesting case of cultural translation. It is also a masterpiece of cinema in its own right. And at the time of writing, a 4K remaster is currently circulating in limited screenings around the UK.

Kurosawa storyboarded every shot of the film

Ran’s development was long (not atypical for a Kurosawa film), being penned in 1975, seven years before going into production and a decade before the film would see the light of day. As was normal for the auteur at the time, in spite of his reputation he had no luck drawing funds within Japan so had to seek support abroad. His admirers George Lucas and Steven Spielberg helped secure money for the director across numerous projects at the time. In that gestation period, Kurosawa storyboarded every shot of the film and shot the other of his late Sengoku jidaigeki (Warring States period drama): Kagemusha. Kurosawa later described this film as his dress rehearsal for the main show – and given the spectacle of Kagemusha, staging as it did a re-enactment of the Battle of Nagashino, that is no small statement.

Ran’s development was long (not atypical for a Kurosawa film), being penned in 1975, seven years before going into production and a decade before the film would see the light of day. As was normal for the auteur at the time, in spite of his reputation he had no luck drawing funds within Japan so had to seek support abroad. His admirers George Lucas and Steven Spielberg helped secure money for the director across numerous projects at the time. In that gestation period, Kurosawa storyboarded every shot of the film and shot the other of his late Sengoku jidaigeki (Warring States period drama): Kagemusha. Kurosawa later described this film as his dress rehearsal for the main show – and given the spectacle of Kagemusha, staging as it did a re-enactment of the Battle of Nagashino, that is no small statement.

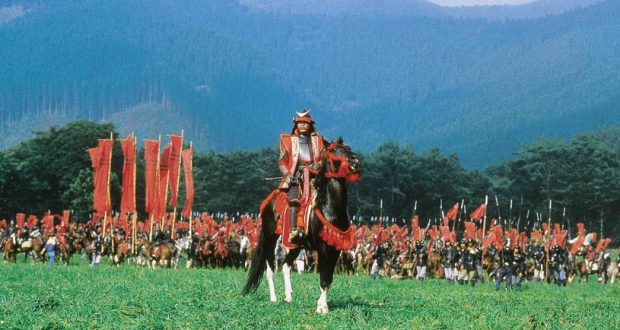

Ran is an immaculately coordinated sight. Regiments of samurai and ashigaru in vibrantly coloured armour clash across an array of astounding landscapes and sets. In desolate plains, period palaces, recreated medieval forts, and the slopes of the Japanese hills, the key players and their great armies enact the Shakespearean drama. And I can’t stress that in an era when we are used to the CG rendered hordes of Peter Jackson and his imitators, whole multitudes of infantry and cavalry all in the flesh is an impressive site.

She remains one of the most iconic screen villains

There are rich seams to be mined in Ran’s cultural translations, cinematography, and storytelling. Perhaps the biggest change it makes to the Shakespearean source material, aside from the setting, are the genders flips. Lear’s daughters are here Ichimonji Hidetora’s sons, and the brothers Edmund and Edgar are replaced by sisters-in-law Kaede and Sué. Though it might be disappointing to see prominent female characters rendered as male, it is largely for the cause of historical context and in particular Kaede’s agency within the story is more prominent than Edmund’s in Lear. The film also offers a repudiation of the sexist archetype of the evil feminising wife. As Kaede manipulates the court and seeks the destruction of the family which destroyed and usurped her own, her inspiration until the end is her personal quest for vengeance. She remains one of the most iconic screen villains for me.

There are rich seams to be mined in Ran’s cultural translations, cinematography, and storytelling. Perhaps the biggest change it makes to the Shakespearean source material, aside from the setting, are the genders flips. Lear’s daughters are here Ichimonji Hidetora’s sons, and the brothers Edmund and Edgar are replaced by sisters-in-law Kaede and Sué. Though it might be disappointing to see prominent female characters rendered as male, it is largely for the cause of historical context and in particular Kaede’s agency within the story is more prominent than Edmund’s in Lear. The film also offers a repudiation of the sexist archetype of the evil feminising wife. As Kaede manipulates the court and seeks the destruction of the family which destroyed and usurped her own, her inspiration until the end is her personal quest for vengeance. She remains one of the most iconic screen villains for me.

The themes of abandonment and the ambivalence (if not hostility) of the gods carry across from the source material but rather than existing in a speculated pagan Anglo-Saxon past, the context here is distinctly Japanese. Buddhist enlightenment fails to stem the cycle of violence which Hidetora set in motion years ago with his campaign of context. The mention of Shinto gods and spirits in Ran only ever refers to their callous behaviour or the mythical actions of the shape-shifting trouble-maker, the fox. Cosmologically, man is placed in a theatre of spiralling violence and all he can do is blaspheme against the gods who have exposed him to such bleak suffering.

The iconic tempest of madness of King Lear is retained in this version

Ran is, if it were not apparent, a rather bleak film. But the disparaging view of humanity never falls into the realm of angst. Its nihilistic philosophy is well-crafted as it emerges naturally from events and imagery. Brief shots of the culminating cloud formations intersperse the film to foreshadow the torment and ruin that has come. Escaping it is as likely as escaping the chaos. As with many Kurosawa films, the internal anguish of characters is externalised: the iconic tempest of madness of King Lear is retained in this version. Though people have agency, much of their efforts are simply spent trying to survive the hardship and violence of existence. The characters struggle to find purpose or meaning when all they can do is endure, but they strive nonetheless. Youngest son Saburo does what he can to fulfil the role of dutiful son and Tango that of dutiful retainer. It is simply the case that when all others abandon these principles, they are an insufficient bulwark to stem this moral decay.

Ran is, if it were not apparent, a rather bleak film. But the disparaging view of humanity never falls into the realm of angst. Its nihilistic philosophy is well-crafted as it emerges naturally from events and imagery. Brief shots of the culminating cloud formations intersperse the film to foreshadow the torment and ruin that has come. Escaping it is as likely as escaping the chaos. As with many Kurosawa films, the internal anguish of characters is externalised: the iconic tempest of madness of King Lear is retained in this version. Though people have agency, much of their efforts are simply spent trying to survive the hardship and violence of existence. The characters struggle to find purpose or meaning when all they can do is endure, but they strive nonetheless. Youngest son Saburo does what he can to fulfil the role of dutiful son and Tango that of dutiful retainer. It is simply the case that when all others abandon these principles, they are an insufficient bulwark to stem this moral decay.

The film has an innate appeal to fetishists of the samurai era (guilty), Kurosawa enthusiasts (also guilty), and Shakespeare fans (you get the idea). However, it shouldn’t be viewed as niche. The film is comprehensible and appreciable even if you have not read the Shakespeare play. One can imagine that in a day and age when audiences have an appetite for bloody political intrigue with medieval battles thrown in from a certain high profile tv show, Ran could certainly find a new swathe of fans.

It is an epic in the traditional sense of the word and guarantees the viewer a marvellous spectacle with rich plotting and characters. It really is a masterpiece.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe