We have six major superhero films out this year. Believe it or not there was a time when this was not the case. The current glut of superhero films is of an era, and this era began with one film, a film that spawned sequels, prequels and spin-offs running to this year and beyond: X-Men. The X-Men franchise has carried on throughout this entire process, and I would argue that the franchise can tell us a lot about how this blockbuster culture has developed. X-Men may have begun this craze, but the film series has been shaped by the culture around these superhero movies more and more with each iteration.

X-Men, the 2000 film directed by Bryan Singer, did not emerge ex nihilo. The two major contexts that formed X-Men were the performance of comic book films in the 1990s and the bankruptcy of Marvel Comics. In the former case, the comics and superhero fare immediately prior to 2000 had been unremittingly campy. The ur-example is the franchise-killer Batman and Robin, a critical and commercial bomb that signified the culmination of a rather contemptuous approach to adapting comics. It relied on gimmicks and nostalgia for crass over-the-top goody antics that were out of step with the contemporary comics’ culture and the cinema-going public at large. This dismissal of engagement with the comics community (and by association, the content) was also shown in what projects were picked up. Studios were willing to green-light films based on strips familiar to the older generations behind production – such as 1930s strip Dick Tracy – but the idea that films could be spun out from properties popular in the present was laughable.

With lower nominal prospects, the production could break away from the previous model of superhero films

Latterly, Marvel’s bankruptcy in the mid-90s led them to hawk the film rights to a lot of the major properties to cover the money they were haemorrhaging. To retain such rights, you need to actually produce a film based on the property. So despite the fact that Warner Bros had lost millions on Batman and Robin and the superhero genre was considered dead to the film industry, Fox had picked up the rights to the X-Men comics at a bargain price so rolled out a modestly-funded blockbuster. Plenty of characters and concepts like Beast and the Danger Room would be cut for cost purposes but Fox wasn’t looking to break the bank on this. The slightly reserved expectations played in the film’s favour. With lower nominal prospects, the production could break away from the previous model of superhero films. It could experiment within the blockbuster formula. It could do something a little different.

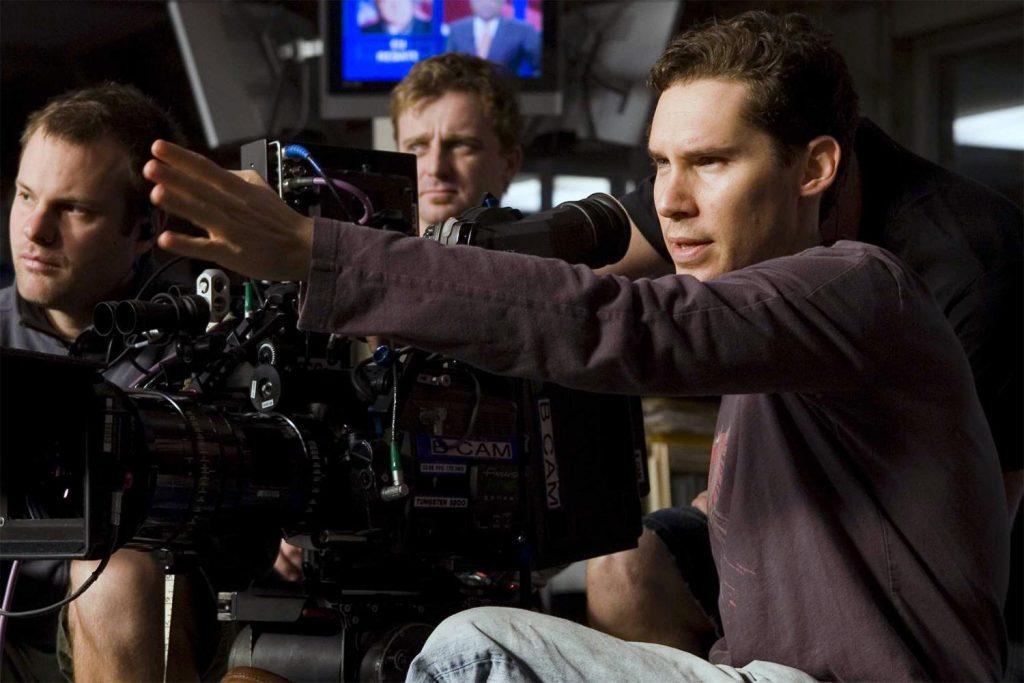

Enter Bryan Singer. A director with no experience in action films and with only a couple of acclaimed but rather high concept films under his belt from 1990s, Singer was an odd choice but his currency with The Usual Suspects got him the role. Not an obvious choice but a sound one who had tackled projects with ensemble casts before. Batting the concept around between director, producers and writers, the idea was to drop the silly tone of the 1990s and approach the content with a sense of maturity. No silly costumes, themes of exploring the persecutions of minorities, and an emphasis on more violent action – somewhat necessitated by Wolverine having one of the most non-PG-13 set of weapons imaginable for a mass market film.

The capacity for the big movie about men in capes to go serious and moody is grounded in Bryan Singer’s work

As an openly gay film-maker, Singer was keen to push the prejudice angle, something he and many others saw as an integral element of the comics. But indeed the approach also followed major trends in the film industry and the comics themselves. X-Men would come after the leather-bound cyberpunk of The Matrix and similarly had a pale palette with dark leather jumpsuits for its heroes. Comics running at the same time and continuing through the early 2000s like Grant Morrison’s run of New X-Men, where already shedding many of the goofy costumes in favour of the more ‘adult’ leather jacket look. Aesthetically, this all reinforced the ethos of ‘take me seriously’.

It is presently something of a fallacy that Christopher Nolan invented the ‘dark’ superhero film. His Dark Knight trilogy has indeed been hugely influential on the style and tone of its successors, but in truth, I think the origins go further back. Nolan’s Batman films were facilitated by X-Men. I mean not simply that without X-Men we wouldn’t have had the films to follow, though that is true, but the capacity for the big movie about men in capes to go serious and moody is grounded in Bryan Singer’s work. Batman Begins has shadows, blood, violent criminals, mind-altering drugs and disquieting imagery. X-Men starts with a sequence in Auschwitz. The former somewhat pales in comparison to the latter.

And here you have the genesis of the new era. Thanks to X-Men, superhero films are financially viable again, they can go dark, and they are willing to draw upon more recent material in the comics.

This is the first in a series of posts on the X-Men film franchise. Check back next week for the second installment.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe