Part 2 of our 4 part series on the X-Men franchise and its impact on comics and the film industry.

X-Men came out in 2000. The following years saw an industry explosion of Marvel films produced by a variety of studios.

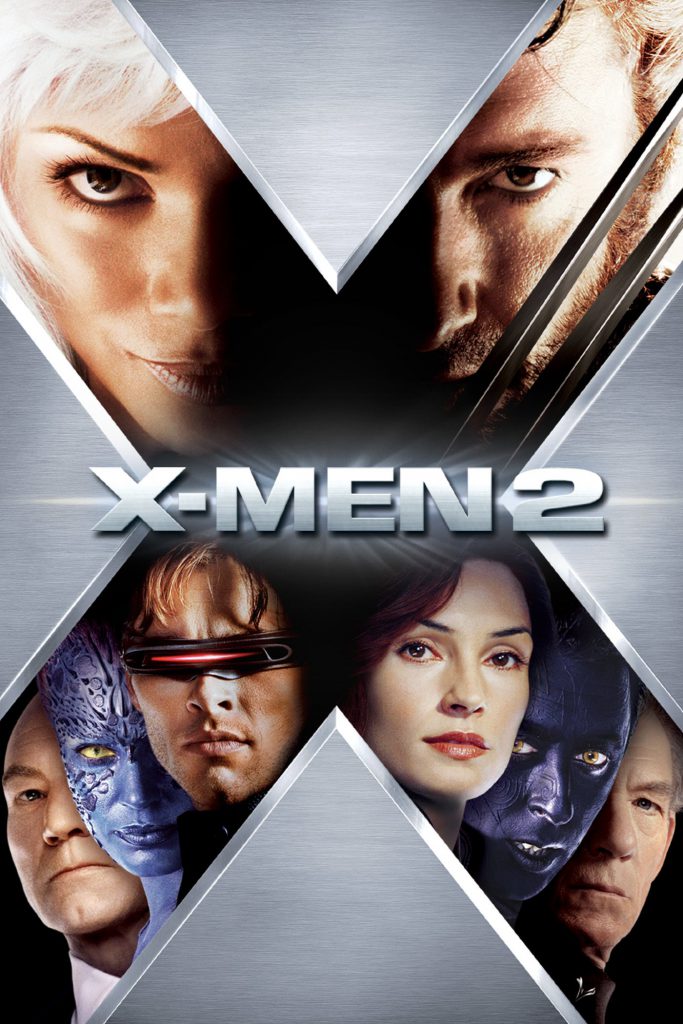

As a result of this market leader proving that superhero films were beyond viable but in fact highly profitable, the field diversifies and the X-Men franchise starts to be enthralled by the mania it has created. Warner Bros, the parent company of DC Comics, was still reeling from Batman and Robin and therefore unwilling to open the floor to films of its comics. In the mean time, the Marvel films cleaned up. The second outing for the X-Men in 2003 (depending on your region either X-Men 2 or X2: X-Men United) exhibits the ascendancy of the genre, with its bigger budget, scale, and production values. Investment was up and now there were rivals to fight off, particularly Sony’s slightly more child appropriate Spiderman films which were faring even better than Singer’s films. The early 2000s were in many ways the brief heyday, and the X-Men franchise, though not the market leader, was a safe cash cow.

But there were major sea changes in the blockbuster market as a result of the content explosion. By this point, a slew of properties were being released year upon year: X-Men, Spiderman, Fantastic Four, Blade, Daredevil, Hulk, Hellboy and of course Batman Begins. After fumbling horribly with Catwoman in 2004, Warner Bros decided to enter the field properly with the Christopher Nolan vehicle. And it didn’t do as well as you might expect or remember. The raving about the mature content and the enthusiasm for the ‘comic book movie aimed at adults’ did not really start until The Dark Knight, a film that tragically and cynically benefitted from the death of one of its stars. Back in 2005, Batman Begins did reasonably, but not great, in what was a poor year for film revenue. It is important more for showing that the studio with exclusive rights to DC material was willing to invest properly in big budget blockbusters. Of course, they had to, given the investment and returns for the rival outings of Sony and Fox. With Batman getting by, it was time to roll out the other big name…

Up to this point, the approach of the superhero franchises was to have direct sequels

Superman Returns directly impacted X-Men III: The Last Stand (again, some variation on the regional names) by sniping franchise helmsman Bryan Singer to direct. Studios needed big name directors to guard their investments. The property that spawned the hype would now be scarred by it. The demand for more and more of this type of content led a major artistic voice behind the franchise leave and be replaced by Brett Ratner – a director much less interested in the thematic intricacies that Singer had woven into his films. Ratner was incapable of, or at least unwilling to, match the serious tone, opting instead for crass campy humour. X-Men III does not simply act as a symbol of the harmful saturation of the blockbuster market that was already taking place. It was a victim of an increasingly ravenous industry but it was also hamstrung by a particular product that it would later be usurped by: the reboot.

Up to this point, the approach of the superhero franchises was to have direct sequels, and above all, the neat trilogy. But we were six years into the phenomenon and these trilogies were drawing to a close, and that meant no continued revenue. But Warner Bros don’t make Superman V (following on from the much older Christopher Reeves films) nor do they reboot the film series from scratch: Superman Returns retcons Superman III and Superman IV: The Quest for Peace and instead hops backward to presume that it immediately follows Superman II (a much better-regarded film than its sequels). This idea of non-sequential films that could hop about the timeline of the overall canon provided opportunities. And with the poor performance of X-Men III, Fox were eager to distance themselves from their last dud while still exploiting the property recognition of the franchise.

Suddenly the ability to mine comic history to source obscure but potentially lucrative characters was essential

Hence we get the next prospect, the subseries of the ‘X-Men Origins’ films. Going into production first was the prequel of the series protagonist Wolverine, and next up was to be the origin of main villain Magneto. But as these projects begin development, the next big year for the industry occurs: 2008. This is the year of The Dark Knight (which would go on to gross over $1 billion internationally) and Iron Man. As a result of the former’s epic box office performance, investment into superhero blockbusters goes into overdrive and the idea that upper film certifications will diminish revenue begins to hold less weight. Because Iron Man was able to out-perform all but Batman in its first outing, with initially limited brand recognition, suddenly the ability to mine comic history to source obscure but potentially lucrative characters was essential. If the new Marvel Studios could rival the established studios with their first film and they had the rights to EVERY single character they had never signed away in perpetuity, then they would prove a big threat. And then there was the internet.

The internet had, of course, been around and a major force before 2008, but it wasn’t until this period that the film industry understood what a force it could be within the comics fandom and how that could spin out into self-generating film publicity. Even X-Men (2000) had allusions to obscure or not immediately relevant content in the comic, but with Marvel Studios steadily gearing up for The Avengers, suddenly the internet became a tool to inspire hype as studios laid clues. Speculation would be rabid. Who would be appearing in the next film? If this character was present, did that mean they were doing that storyline? On top of the move towards non-linear series building, the internet community allowed accessibility and viability to increasingly complex branching narratives of films that reflected the, at times, rather impenetrable nature of the comics. With Marvel Studios actively exploiting this, with their mission statement at the end of Iron Man to make an Avengers film, Fox had lost the initiative. It was time to follow suit leading to the next era of the X-Men films.

You can read Part 1 of this series here. Check back next Friday for Part 3.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe