The conclusion to our four-part series on the evolution of the X-Men film franchise. If you missed it, be sure to start from the beginning!

By the present year of 2016, the blockbuster subgenre that X-Men began has become a hulking and efficient industrial process dedicated to churning out its product. What began as a modestly funded franchise led by some auteur sensibilities is now a slavish sheep rather than innovative shepherd to the trend it started.

Hence we have Deadpool. The intricacies of Deadpool as a character and comic can be written about elsewhere, suffice to say that the character had a cult following with pre-established interest. No one had been satisfied with the treatment of Deadpool in his X-Men Origins: Wolverine cameo. The role of online support was particularly in evidence getting this new project off the ground. Movie stars had cottoned onto the fact that getting a recurring role in one of these super-franchises was a guaranteed sustained income and kept their faces in cinemas regularly. Money and profile enhancement being what they are, stars now mounted very public campaigns to secure these roles, taking full advantage of the pre-established fan bases and the online circus surrounding superhero properties. Whereas previously, negotiations may have occurred with producers and agents, now Ryan Reynolds was able to popularise the idea of him playing Merc-with-the-Mouth. Evidently it worked.

It is a bizarrely regimented courtship of pitching highly-prized corporate properties to an audience seeking to ascribe artistic depth to a movie conveyor belt

The degree to which the surrounding culture of superhero comics have been co-opted by the film industry is shown by the annual San Diego Comic Con. America’s largest event in the medium, it has gone from simply a geek haven to a mass publicity event for films. If a studio wants to generate buzz around a film, they make a big show at Comic Con. The format of the sales pitches for stars banking on superhero roles is very much set by now. Stars campaigning for or continuing to promote their roles will talk about staying ‘true to the roots of the character’, how they are relevant and important in some fashion or another, and how superheroes are the modern American mythology. It has all the variety of a Miss America acceptance speech. It is a bizarrely regimented courtship of pitching highly-prized corporate properties to an audience seeking to ascribe artistic depth to a movie conveyor belt. Reynolds was a dab hand at this having gone through a similar rigmarole with Green Lantern, where his dazzling of the fans at conventions and online was of much higher quality than the film that reached cinemas.

Now it is once again that we return to the legacy of Christopher Nolan. I have previously asserted that Nolan is incorrectly credited with inventing the dark superhero film, but his particular version of pervasive grimness was an entity unto itself. With his Dark Knight films wrapped, he took a backseat to produce the newest Superman reboot, Man of Steel. The extent of his trademark humourlessness was excessive in the extreme. Whereas Marvel films were bright and colourful, with quips and smug one-liners, not a smile was to be cracked in a DC film – even if the superhero was a space alien wearing a bright red and blue costume. Deadpool actively reacted against this, but also sought to outmanoeuvre the ‘accessible’ fun rival of Marvel: both were funny but Deadpool would be ADULT. In a crowded marketplace with several properties failing to now gain traction if they weren’t part of a super-franchise, diversifying and fulfilling niches has become essential.

Fox had to tie down and lay claim to big name characters with links across many properties

This was a particularly crucial battle for Fox. While they held the film rights from Marvel, but Marvel had proven aggressive in reclaiming and integrating properties that they sold off in desperation at the turn of the millennium. Fox had failed to green light a new Daredevil movie since the dud in 2003, so their rivals had leapt on the rights when they became available due to the property going unused. Similarly, with so much of the Marvel comics universe interlinked, Marvel was now more confident pressing for joint rights on characters that straddled properties nominally held by both Marvel and other studios.

Hence, Quicksilver (originally an X-Men character) was in Days of Future Past but Marvel had successfully gotten a ruling to include him in Avengers: Age of Ultron since the character was heavily associated with that team in the comics. Fox had to tie down and lay claim to big name characters with links across many properties, which Deadpool had in abundance, to stay in the game. Fox, therefore, brought Deadpool to cinemas this year and its huge success in spite of its adult content and thus higher certification is perhaps the last innovation we can expect from the Fox franchise. We will see a new glut of gorier films: Wolverine III promises to have just as graphic sensibilities if not more than its self-aware precursor.

Hence, Quicksilver (originally an X-Men character) was in Days of Future Past but Marvel had successfully gotten a ruling to include him in Avengers: Age of Ultron since the character was heavily associated with that team in the comics. Fox had to tie down and lay claim to big name characters with links across many properties, which Deadpool had in abundance, to stay in the game. Fox, therefore, brought Deadpool to cinemas this year and its huge success in spite of its adult content and thus higher certification is perhaps the last innovation we can expect from the Fox franchise. We will see a new glut of gorier films: Wolverine III promises to have just as graphic sensibilities if not more than its self-aware precursor.

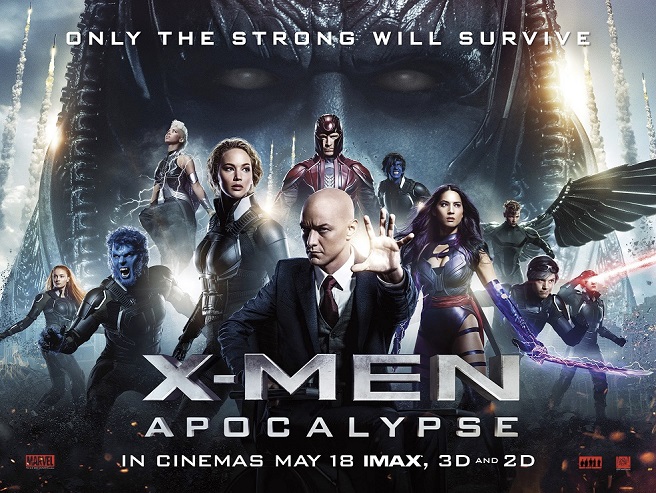

My observations on the creative stagnation of the franchise are not, however, epitomised by Deadpool for all that it was assembled as a precise marketing strike, seeking to outflank the Marvel cash cows. The second X-Men film of 2016 is not the quality nadir of the franchise (we are long past the worst films, thank god) but X-Men: Apocalypse does exhibit the derivative studio process that now defines this industry. Once again, we must return to Man of Steel. Nolan’s film has now become a codifier in its own right. Coupled with the ever escalating levels of destruction in each subsequent Marvel film, the annihilation porn of Man of Steel went beyond the scale of even New York being invaded by extraterrestrials. The superhero film, initially quite modest in the scale of its set pieces which usually devolved to two blokes fighting, now demanded giant blue beams to shoot from the sky and level major urban population centres. To an extent, Singer had avoided this in returning to the series. Big things happen but not on the scale of devastation as the Nolan-produced/Snyder-directed movies or the expanding destructive scope of the big Avengers team-ups. The middle fight scene of Days of Future Past was two mutants punching each other in a fountain, after all.

Apocalypse shows its DNA very clearly

Now we catch ourselves up fully and reach X-Men: Apocalypse, the film which solidifies the prevalent trends of the genre in a single entity. Establishing yet more branching continuity, tidying bits of the franchise here and there, building in new team members with each instalment, configured around presenting its recognisable stars no matter how irrelevant, and adhering to the industry standard of global mass destruction – Apocalypse shows its DNA very clearly. So many of its elements are not contingent on narrative or quality film-making but on the promotion and expansion of a financial asset that needs to be nurtured and grown so it can reap more revenue. Watch the first X-Men film and compare to this latest outing to see the inexorable forces of the superhero genre morph and contort the parent that spawned it.

The X-Men franchise is a big and sprawling beast at this point and as I hope I have shown one perfect for analysing the growth, maturation (and corruption) of one the defining features of our contemporary pop culture: the superhero film.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe