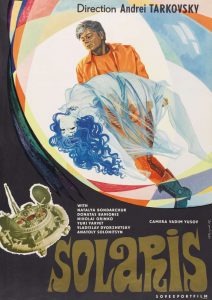

Few phrases intimidate both casual and auteur film-goers as the words ‘Russian cinema’. Renowned for its epic scope, long running times, and dense philosophical content, the classic films of Russia boast some unapologetically difficult viewing experiences. There are of course many masters of Russian cinema to laud: Eisenstein, Bondarchuk, Kosintsev. It is Tarkovsky, however, who can be attributed with one of the most influential science fiction films ever to be produced: 1972’s domineering Solaris.

Whether you have seen it or not, you know the plot, so ingrained is it in the wider popular consciousness. Kris Kelvin is dispatched to a space station orbiting the bizarre planet Solaris where strange goings on are afoot. He has to restore contact to the station and ascertain what is going on. Little does he know what he will have to confront when he arrives at Solaris station.

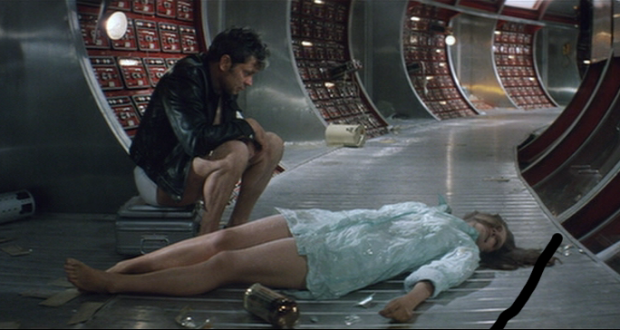

The film adapts the identically titled book by Stanislaw Lem, though ultimately Tarkovsky took a very different approach. To such an extent, in fact, that Lem was rather dismissive of the final result. The plot remained broadly the same. Kelvin arrives to find one of the three scientists on the station dead and soon comes face to face with one of the apparitions that have been haranguing the inhabitants of the station. In his case, he comes face-to-face with his dead wife.

Lem accused Tarkovsky of essentially adapting Crime & Punishment rather than his own novel

Whereas the book is primarily framed around the limitations of human communication with entities of an entirely disparate nature – the mysterious and possibly sentient planet Solaris, in this case – the film is concerned overwhelming with the intimate connection between Kelvin and Hari. It’s a messy take on love which is a force of revelation and truth but is, in the cheery manner of the film, basically doomed. Kelvin’s reunion with his dead wife sees him lose purpose, sliding into a slobby, depressive state. Furthermore, each visitor, a fragment of one’s past made real again by Solaris, confronts the individual with some prevailing truth about their subconscious. In Kelvin’s case, his dead wife Hari represents his guilt at not loving her when she lived and his emotional isolation.

Whereas the book is primarily framed around the limitations of human communication with entities of an entirely disparate nature – the mysterious and possibly sentient planet Solaris, in this case – the film is concerned overwhelming with the intimate connection between Kelvin and Hari. It’s a messy take on love which is a force of revelation and truth but is, in the cheery manner of the film, basically doomed. Kelvin’s reunion with his dead wife sees him lose purpose, sliding into a slobby, depressive state. Furthermore, each visitor, a fragment of one’s past made real again by Solaris, confronts the individual with some prevailing truth about their subconscious. In Kelvin’s case, his dead wife Hari represents his guilt at not loving her when she lived and his emotional isolation.

That is not to imply that Hari, played by Natalya Bondarchuk who Tarkovsky thought gave the best performance in the film, is a passive figure for Kelvin to simply project his emotional crisis onto. Ultimately the point of love is that it defines and limits each of the pair. Complicating the picture further, Hari is forced to confront her existence as a constructed entity. As she becomes more self-aware and less bound by the foundation of Kelvin’s memory from which she is built, she becomes increasingly hopeless about the nature of existence. She can only live within range of Solaris and, unlike Kelvin, can never return to the vibrant and busy earth. Kelvin can indeed choose love but if he does he chooses to stay with her on this decrepit station. To return home is to become enmeshed in the distractions of life, a vibrant smoke-screen that inures the individual to the truth being. It offers movement and development but is a Platonic illusion with no inherent value.

Brainy as the film is, Solaris is obsessed with bodies: feverish, aging, sexually-yearning bodies

As with so much good science fiction, the journey outward into space is an opportunity to travel inward. After the initial (more exposition-oriented) prologue, the majority of the film simply follows the characters around the cloistered structure of the station that overlooks the swirling surface of Solaris. The two remaining scientists on the station, Snaut and Sartorius, respond to the visitations of their barely-glimpsed guests with semi-drunken resignation and fearful clinical detachment, respectively. These characters effectively spend their time staring into a cosmic abyss or their navels. The station is the perfect metaphor for the film’s conception of humanity. You can look out onto an alien entity desiring to make contact but be trapped within the confines of your own flawed humanity. The harder these people try to reach Solaris, the more they are pushed back to confront themselves. The outlook is ultimately summed up by Snaut when he opines ‘We don’t need other worlds. We need mirrors’.

As with so much good science fiction, the journey outward into space is an opportunity to travel inward. After the initial (more exposition-oriented) prologue, the majority of the film simply follows the characters around the cloistered structure of the station that overlooks the swirling surface of Solaris. The two remaining scientists on the station, Snaut and Sartorius, respond to the visitations of their barely-glimpsed guests with semi-drunken resignation and fearful clinical detachment, respectively. These characters effectively spend their time staring into a cosmic abyss or their navels. The station is the perfect metaphor for the film’s conception of humanity. You can look out onto an alien entity desiring to make contact but be trapped within the confines of your own flawed humanity. The harder these people try to reach Solaris, the more they are pushed back to confront themselves. The outlook is ultimately summed up by Snaut when he opines ‘We don’t need other worlds. We need mirrors’.

The film is almost dismissive of the actual scientific endeavours at Solaris Station. In fact, the resolution is an almost nonchalant dismissal of the paranormal goings-on at the station, which leaves the inhabitants free of their troubling visitors. It’s not a film prefigured around its narrative developments though. Solaris doesn’t hinge on twists or turns. It simply plods along and concludes on its philosophical apotheosis. And I could be barking entirely up the wrong tree with my interpretation. It’s a film that does not make it easy to derive meaning, though you can be sure that the film and its themes were crafted with rigorous intent. I puzzle over individual scenes, and each one is pregnant with meaning. You could easily be led up an erroneous thematic tangent by not giving due emphasis to a shot or line of dialogue. Or perhaps I am missing the point entirely because I am trying to apply an inadequate rational interpretation that masks emotional truth, just like the characters in the film…

The film is almost dismissive of the actual scientific endeavours at Solaris Station. In fact, the resolution is an almost nonchalant dismissal of the paranormal goings-on at the station, which leaves the inhabitants free of their troubling visitors. It’s not a film prefigured around its narrative developments though. Solaris doesn’t hinge on twists or turns. It simply plods along and concludes on its philosophical apotheosis. And I could be barking entirely up the wrong tree with my interpretation. It’s a film that does not make it easy to derive meaning, though you can be sure that the film and its themes were crafted with rigorous intent. I puzzle over individual scenes, and each one is pregnant with meaning. You could easily be led up an erroneous thematic tangent by not giving due emphasis to a shot or line of dialogue. Or perhaps I am missing the point entirely because I am trying to apply an inadequate rational interpretation that masks emotional truth, just like the characters in the film…

Did I mention this film was Russian?

In fact, such is the success of the film in its technical and thematic craftsmanship that I went to see it intent on pulling apart and analysing Tarkovsky’s cinematic style. In fairly short order, that went out the window. The film demands attention for its human drama. As slow and pensive as it is, Solaris is bizarrely enrapturing and defies the viewer not to be swept up in its simple tale of love and self-discovery.

Is it an easy or action-packed watch? Lord, no. It’s a film designed explicitly to elevate science fiction and cinema beyond the lower endeavours of pulp traditions. But there’s a reason that Solaris and Tarkovsky’s influence pervades film at large. If you can capture someone’s attention for a three-hour-long, story-light, philosophising, borderline-nihilistic, science fiction psychological romantic drama, you’ve made a masterpiece of cinema.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe