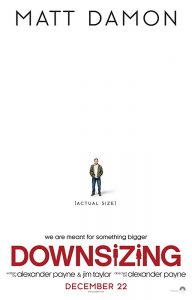

I am an established fan of Alexander Payne. His films usually deal with strong concepts. You engage with them through strong and funny character-driven stories. He also has an interest in middle America and people stuck in their tracks. There’s a rich theme of people trapped in cycles of underachievement and disappointment which Payne can really mine. Downsizing is his first outing with an actively surreal conceit and has much to recommend it but ultimately is one of his more middling films.

People can now get small. After a miniaturisation is pioneered by Scandinavian scientists, people can be shrunk to roughly 5 inches tall. Once downsized, people naturally consume a fraction of the resources to continue living. This has massive implications for reducing the impact of human life on the planet. By the time Paul and Audrey Safranek consider the process, the technology has been monetised. Downsized people can move into affluent gated communities catering to their size, where their more modest savings translate to staggering material wealth.

The best sections revolve around satirising the conceited ‘model’ community

This all serves, surprise surprise, as a microcosm of American society. It becomes apparent that the pampered retirement lifestyle benefitting cosy middle class and uber-wealthy Americans is built on the back of broken promises and economic exploitation. A technology designed to help rescue the planet for everyone is turned to the benefit of the people that were doing well anyway and are totally in it for themselves. Utopia is only a utopia for rich white folks, as usual.

This all serves, surprise surprise, as a microcosm of American society. It becomes apparent that the pampered retirement lifestyle benefitting cosy middle class and uber-wealthy Americans is built on the back of broken promises and economic exploitation. A technology designed to help rescue the planet for everyone is turned to the benefit of the people that were doing well anyway and are totally in it for themselves. Utopia is only a utopia for rich white folks, as usual.

The film succeeds best in the first half when we get to grips with the introduction and impact of this technology through the eyes of Paul Safranek (Matt Damon). He’s a normal guy with disappointed ambitions who wants to do better for himself and his wife. Whilst considering the change, we see all the immaculate air-brushed advertising for the lifestyle, the resentment building amongst the full-sized, and the abuses of power the technology enables in the third world. Through to about the halfway mark, Payne shows us how well-thought through the concept is.

Downsizing meanders through its later sections and trips up on some egregious clichés

Alas, focus is lost for the latter part of the film. Safranek, now divorced and on the economic bottom-end of shrunk community, indulges in a quest of self-discovery with Hong Chau’s Vietnamese immigrant Ngoc Lan Tran. Chau does give a good performance but her part is problematic. She is a stereotype. Now, the inclusion of an immigrant worker with poor English is not necessarily bad in and of itself. But when the disadvantaged but soulful and wise character is there to galvanise the spiritual and emotional development of our white protagonist, we are in unfortunately clichéd territory.

Alas, focus is lost for the latter part of the film. Safranek, now divorced and on the economic bottom-end of shrunk community, indulges in a quest of self-discovery with Hong Chau’s Vietnamese immigrant Ngoc Lan Tran. Chau does give a good performance but her part is problematic. She is a stereotype. Now, the inclusion of an immigrant worker with poor English is not necessarily bad in and of itself. But when the disadvantaged but soulful and wise character is there to galvanise the spiritual and emotional development of our white protagonist, we are in unfortunately clichéd territory.

This isn’t the only issue. As tight as the concept is the first half, the expanding scope gets less taut and insightful. Christopher Waltz and Udo Kier’s extravagant Eurotrash privateers are fun and underscore a point about underregulated commerce, but don’t serve a purpose after a point. They literally take the film sailing down a far more mawkish route by the close. Downsizing is funny, well-made and does have some good points to make, but the middle-to-end section is drier, flabbier and lacks polish. A genuinely interesting if not entirely successful outing.

Verdict: A great concept that outgrows its merits.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe