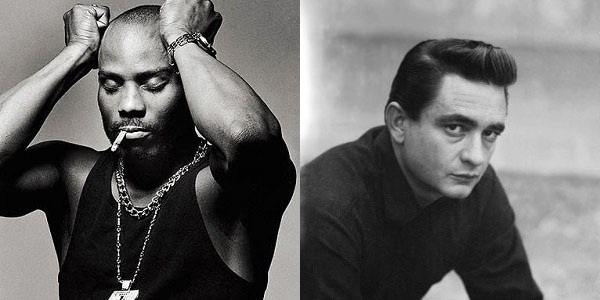

DMX is the hip hop Johnny Cash. Let me explain.

Johnny Cash is a legend of American music. Just a year into his recording career he was the most prolific of the pioneering Sun Records’ ‘Million Dollar Quartet’, alongside Carl Perkins, firebrand hellion Jerry Lee Lewis and the cultural phenomenon Elvis Aaron Presley.

In contrast, DMX hasn’t released a decent album in a decade, which makes it easy to forget the impact his arrival had. In an era of shiny suited, pop-sampling production from the then Puff Daddy, the claustrophobically close atmosphere of threat and murk of X’s appropriately titled ‘98 debut, It’s Dark and Hell is Hot, was a sulphurous blast of millennial fury, defining the opposition between authentic street rap and commercial pop in much the same way Cash came to do with the rise of outlaw country in the ‘70s in opposition to the saccharine ‘Nashville Sound’. X arrived as a fully formed, (literally) barking, larger than life figure of aggression. It’s Dark and Hell is Hot sold a quarter of a million records in its first week, entering the US chart at #1, as his second album did later that same year, and third, the year after that. In just 20 months, DMX released three albums that would collectively go platinum 12 times.

Cash himself didn’t have the most consistent career, much as his rehabilitated reputation denies it. Someone once pointed out to me there were only three real ages of Cash significance – with Sun Records in the ‘50s; around his prison live albums in the late ‘60s; and when bearded production sage Rick Rubin resurrected his fortunes with the American albums of the ‘90s and ‘00s. There are gems between those periods of course, but it’s an uneven path. Both Cash and DMX also suffered deprived childhoods – Cash picking cotton on his family’s post-Depression Arkansas farmstead, while X was raised on welfare, in roach-infested Yonkers, NY apartments, by his abusive single mother before being abandoned to a group home. The real similarities between them though are in the music, and in both men’s embodiment of the persona of wrong. We are after all talking here about a man who performed songs about cocaine abuse, meaningless violence, firearms, desperation and cold-blooded murder – but we’re also talking about DMX.

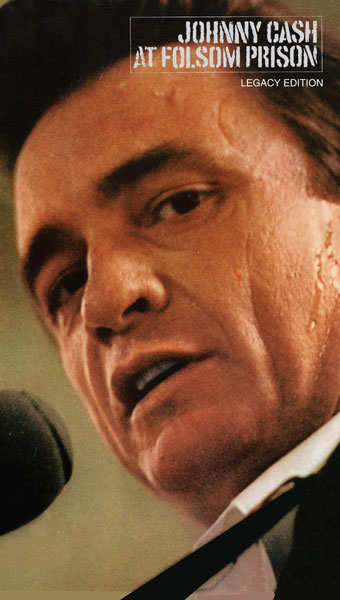

Cash’s subject matter was the darker facets of humanity, and those who fall outside of society – from poverty, guilt, heartache and sorrow to ‘25 Minutes To Go’’s death row executionee, the drug-crazed uxoricide of ‘Cocaine Blues’ and the incarcerated murderer of ‘Folsom Prison Blues’ – all delivered in simple language over the spare, driving ‘boom-chicka-boom’ rhythm devised by his Tennessee Three. That Cash didn’t write some of these songs is made irrelevant as Cash doesn’t sing about these outsiders, but as them – creating an understanding heard in the joyous screams of the prison audiences (a young Merle Haggard among them) on his Folsom and San Quentin live albums. Confronting the audience like this – giving social issues a human face and leaving the audience to draw their own conclusions – was a key thread in the creation and personification of gangsta rap by Ice-T and N.W.A. decades later, an approach taken still further with DMX’s arrival.

Cash’s subject matter was the darker facets of humanity, and those who fall outside of society – from poverty, guilt, heartache and sorrow to ‘25 Minutes To Go’’s death row executionee, the drug-crazed uxoricide of ‘Cocaine Blues’ and the incarcerated murderer of ‘Folsom Prison Blues’ – all delivered in simple language over the spare, driving ‘boom-chicka-boom’ rhythm devised by his Tennessee Three. That Cash didn’t write some of these songs is made irrelevant as Cash doesn’t sing about these outsiders, but as them – creating an understanding heard in the joyous screams of the prison audiences (a young Merle Haggard among them) on his Folsom and San Quentin live albums. Confronting the audience like this – giving social issues a human face and leaving the audience to draw their own conclusions – was a key thread in the creation and personification of gangsta rap by Ice-T and N.W.A. decades later, an approach taken still further with DMX’s arrival.

If Cash offers the reflections after the fact, the sentence given and the dust settled, X offers a mindset where crimes aren’t caught and you’re more likely to suffer them yourself; an elemental landscape of the fog between the light and dark, where murder, bloodshed, assault, violence, drugs and despair churn in an unending cycle. The despair is without context as, while money is made, rarely is even the possibility of escape visible, survival at others’ expense being the only feasible goal and how things are being simply how things are. This is not the entrepreneurial/criminal striving of most gangsta rap, but a world of brute survival, with the only moments of respite in praying.

And when I say praying, I don’t mean figuratively. I don’t mean ironically, or as a narrative device. The other striking similarity between ‘the man in black’ and ‘dark man X’ is their Christianity. I once had a particularly Christian flatmate who was sure he’d heard that DMX sacrificed animals in satanic rituals. Admittedly not so far-fetched given he’s on the cover of sophomore album Flesh of my Flesh, Blood of my Blood soaked head to toe in, yes, blood, but incongruous given that X does indeed pray, on record, to God. Each DMX album features an a cappella prayer, asking for forgiveness and searching for hope, and not only is God in the house (conversing with X, and voiced by him, in ‘The Convo’ and ‘Ready To Meet Him’) but so is the devil on the ‘Damien’ tracks, voiced by X in a nauseatingly high, insidious voice. While Cash’s beliefs and morals are front and centre in a lot of his catalogue, only occasionally are they foregrounded as more than implicit in the situations X confronts his listeners with.

Where the two do differ, is with regards to drugs. Not necessarily in their stance towards them, so much as their preferences and ability to do without. In the hard-touring days of the ‘50s and ‘60s, Cash became hooked on amphetamines and dexedrine, supposedly to maintain the pace, eventually being busted in El Paso in ’65 with a guitar case full of pills. DMX on the other hand, prior to his career in music, was hooked on cocaine, on which he would periodically fall back.

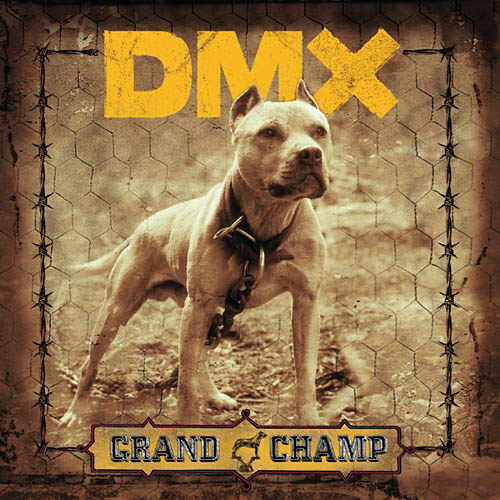

Both had their credentials in regards to their subject matter bolstered by their encounters with the law. Cash’s occasional arrests were known at the time, playing to his outlaw image and occasionally turning up in his songs, but rediscovering his faith and his marriage to June Carter led to his getting clean at the end of the sixties. Around the release of DMX’s fifth album (2003’s Grand Champ – his last to achieve platinum status or the #1 spot), he similarly announced he would be retiring from music (as Ma$e had done) to focus on bible study.

Both had their credentials in regards to their subject matter bolstered by their encounters with the law. Cash’s occasional arrests were known at the time, playing to his outlaw image and occasionally turning up in his songs, but rediscovering his faith and his marriage to June Carter led to his getting clean at the end of the sixties. Around the release of DMX’s fifth album (2003’s Grand Champ – his last to achieve platinum status or the #1 spot), he similarly announced he would be retiring from music (as Ma$e had done) to focus on bible study.

It didn’t quite work out like that though. Retirement in hip hop is never easy (ask Jay-Z) but coming back often isn’t problem-free either (Ma$e’s return having left him a punchline). In place of bible study what we actually got was a middling sixth album and latterly an increasingly bizarre string of rehab stints, courts appearances and arrests, on charges of everything from swearing, speeding and back taxes to drug and firearm possession, animal cruelty and impersonating an FBI agent. A lacklustre seventh album dropped last year, retreading old ground, and X has continued to insist he’s preparing to release a gospel album. There have been flickers of hope (a barnstorming BET Awards performance in 2011 reminded a lot of people how many great tracks DMX actually had) and signs to the contrary (the footage in VH1’s Behind The Music of X taking the stage hours late at a local club, doing a half-hearted, drunken performance like a former ‘90s popstar), but a new low was perhaps reached last month, in the latest of several reality tv appearances, with X seemingly erratic and deep in denial.

Johnny Cash showed it was possible to come back from addiction and maintain a standing as a revered figure in music, while continuing to address the dark themes he’d wrestled with before. His art grew and evolved through this process though, and as each DMX album now seems to offer the diminishing returns of repetition, and each sighting of him has a little more of the terrifying aspect Amy Winehouse’s last festival appearances had, the question of whether we’ll get the chance to see him attempt the same looms larger.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

The DMX story is a truely sad story on how the industry can really get the best out of entertainment artist and use them up until there is nothing left of them.