The distinction between past, present, and future is only an illusion, however persistent.

Albert Einstein

When I was young, I had a lot of trouble sleeping. My parents tried everything – from soothing music to almost meditation techniques, I was never very good at nodding off. One of my favourite things was listening to stories. I enjoyed being read to as well as told interesting tales – made up or mundane stories of my parents’ days at work.

There was one particular story that always stuck with me. My father has never been a big reader, but he has always been a fan of science fiction. I remember him paraphrasing Ray Bradbury’s ‘A Sound of Thunder’ as one of my bedtime stories. The idea that life as I knew it could be destroyed by someone simply stepping on a butterfly when they shouldn’t have, was an astonishing idea. There began a lifelong love of time travel stories.

What is time?

Time is primarily perception. Humans measure their lives and experiences in terms of the past, present, and future. This is considered the ‘realist’ view, as put forward by Sir Isaac Newton. His theory is that time is a dimension of the universe (and therefore an important part of all physics) and that time is linear and measurable. This view – that time exists irrespective of our experience of it – is the basis of the standard physics view. But it isn’t the only view.

Time is primarily perception. Humans measure their lives and experiences in terms of the past, present, and future. This is considered the ‘realist’ view, as put forward by Sir Isaac Newton. His theory is that time is a dimension of the universe (and therefore an important part of all physics) and that time is linear and measurable. This view – that time exists irrespective of our experience of it – is the basis of the standard physics view. But it isn’t the only view.

There is also a view put forward by Gottfried Leibniz and Immanuel Kant: that time is not something independent of us. Time does not exist in the same way that a physical space does, it is only how we interpret events and experiences.

Space is not something objective and real, nor a substance, nor an accident, nor a relation; instead, it is subjective and ideal, and originates from the mind’s nature in accord with a stable law as a scheme, as it were, for coordinating everything sensed externally.

Immanuel Kant

What is time travel?

Time travel is a concept that has been explored in science fiction since the beginnings of the genre. But there are a number of different theories surrounding this fanciful idea. I am going to ignore the idea of time travel as H.G. Wells imagined it – travelling in time only, but not space. Besides, I never really could get over the fact that he named a major character in the novel Weena.

The first theory, which does not support the idea of free will, says that there is only one, unchangeable timeline. Things happen the way that they do and that’s that. There is no changing it, you cannot travel back in time and influence the future. You would not be able to interact with the past or the future if you manage to travel there. This is my idea of boring, pointless time travel. What would be the point in travelling to another time (unless I was a historian) if I couldn’t interact with it?

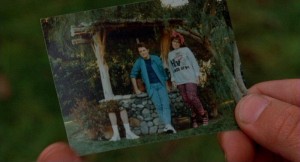

The second theory, and the most commonly presented in science fiction is that of the changeable timeline (which can cause dangerous time paradoxes and alternate/divergent timelines). This is the kind of time travel that Ray Bradbury explores in ‘A Sound of Thunder’ and in films such as Back to the Future (parts I, II, and III).

The second theory, and the most commonly presented in science fiction is that of the changeable timeline (which can cause dangerous time paradoxes and alternate/divergent timelines). This is the kind of time travel that Ray Bradbury explores in ‘A Sound of Thunder’ and in films such as Back to the Future (parts I, II, and III).

The third theory is that of an infinite number of alternate timelines coexisting at any given time. Think of the very un-sci-fi Gwyneth Paltrow film Sliding Doors. In some timeline somewhere, all the possibilities are played out. This could also be considered a multiverse theory, for instance, the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. Professor Brian Greene discusses nine types of multiverse theories in his book, The Hidden Reality: Parallel Universes and the Deep Laws of the Cosmos.

The changing moral compass of time travel stories

Many of the early time travel stories, such as ‘A Sound of Thunder’, are cautionary tales. They warn us about changing our history and try to comfort us in our current existence – that things are, in a sense, the way they were always meant to be. I believe it is part of the human experience to wonder what things could have been like if you had acted or chosen differently. That desire to go back and change things for the better. The time travel stories often warned us that these were pointless dreams – that we could never really change anything even if we managed to invent a system of time travel. The smallest change could cause a catastrophic change.

The impetus of these stories, however, seems to be changing. Take a look at the three Back to the Future films, for instance. In the first film, the entire way through the film the lesson being hammered home is that one should not interfere with the timeline/events of the past. Of course, this is ultimately ignored when Doc Brown sticky-tapes Marty’s letter back together and wears a bullet-proof vest for when the Libyans attacked (or is it – I suppose we don’t know that he didn’t originally wear a bullet-proof vest without the warning). The entire plot of the film is driven by Marty’s need to fix the timeline before his own existence is erased.

The impetus of these stories, however, seems to be changing. Take a look at the three Back to the Future films, for instance. In the first film, the entire way through the film the lesson being hammered home is that one should not interfere with the timeline/events of the past. Of course, this is ultimately ignored when Doc Brown sticky-tapes Marty’s letter back together and wears a bullet-proof vest for when the Libyans attacked (or is it – I suppose we don’t know that he didn’t originally wear a bullet-proof vest without the warning). The entire plot of the film is driven by Marty’s need to fix the timeline before his own existence is erased.

Back to the Future Part II, however, takes a very different view. Doc Brown returns from a brief stint in the future and takes Marty forward in time with him – specifically so that they can change the events of the future. Gone are Doc’s concerns about changing the timelines – he deliberately sets out to do just that. Of course, this spins out of control and they have to fix a number of differing timelines. The lesson is still not learned, however, when Doc Brown let’s Clara live in Back to the Future Part III, even after learning that Clara should have died in the ravine. What domino effect will be caused by his careless actions?

The cautionary kind of time travel story is also reflected in one of my favourite Star Trek: The Original Series episodes, ‘The City on the Edge of Forever’, guest starring Joan Collins. Doctor McCoy inadvertently changes history by saving Edith Keeler (Joan Collins) from dying in a car accident. When Kirk and Spock join McCoy in the past to try and set things straight, poor romantically challenged Kirk falls for Keeler. The timeline tries to restore itself – throwing the Edith into the path of another motor vehicle. McCoy is restrained and Kirk lets her die. Oh, how heroic and emotionally poignant. But the lesson is clear – it is more important to keep the integrity of the timeline that save Edith for selfish reasons.

The cautionary kind of time travel story is also reflected in one of my favourite Star Trek: The Original Series episodes, ‘The City on the Edge of Forever’, guest starring Joan Collins. Doctor McCoy inadvertently changes history by saving Edith Keeler (Joan Collins) from dying in a car accident. When Kirk and Spock join McCoy in the past to try and set things straight, poor romantically challenged Kirk falls for Keeler. The timeline tries to restore itself – throwing the Edith into the path of another motor vehicle. McCoy is restrained and Kirk lets her die. Oh, how heroic and emotionally poignant. But the lesson is clear – it is more important to keep the integrity of the timeline that save Edith for selfish reasons.

More and more time travel stories are taking a cavalier approach to the changing of events, however. It is common for people to want to feel more in control of their lives, and time travel becomes an easy way to achieve this. But is this really what time travel stories should be telling us? Should Marty McFly have gone into the future to save his son or should Doc Brown just given him some parenting books? The lesson to take from these stories shouldn’t be – oh don’t worry, there’s always a short-cut fix.

Let’s look at the films Groundhog Day and the new Richard Curtis rom-com, About Time. I love Groundhog Day, but I am well aware of its many flaws. Bill Murray’s Phil Connors uses each day that he gets to live again as another day he can try to win over Andie MacDowell. He is like the ultimately Barney Stinson (How I Met Your Mother), doing the ultimate ‘play’ in order to get the woman to sleep with him. He picks up on clues, learns what she likes and what she doesn’t, so that he can manipulate her. Sure, he doesn’t do this in a malicious way, he grows as a person and learns to be kinder, etc, but he is manipulating her. Is that really ok?

In About Time, the main character, Tim (Domhnall Gleeson), uses time travel to change his life for the better. If things don’t work out how he wanted them to, he goes back in time and changes it. He learns a few lessons along the way – for instance, when he goes back in time before his daughter is born, when he returns to the ‘present’ his child is no longer the same. This is apparently a side effect of having travelled back before a child is born. But this lesson isn’t applied more universally – no ultimate lesson about messing with timelines or letting things happen the way that they do (without interference). The time travel is always used for selfish ends – even ‘helping’ his sister is a selfish act.

These films have one important thing in common: the women in the stories are not aware that the men can (and are) use time travel to influence their lives. Variety journalist Leslie Felperin comments on this in About Time as creating a ‘fundamental lack of honesty in their relationship.’ This is a real issue. The initial cautionary tale element of time travel has been lost in favour of using time travel to control one’s own life, as well as manipulating those around you. How would Andie MacDowell or Rachel McAdams react if they knew that their partners were, in effect, ‘cheating’ their way through the relationship? I can tell you – if I found out that my partner was able to win every fight (or avoid it) by reliving the day, I’d be beyond pissed.

I would like to see a few more traditional time travel stories where characters ponder the implications of changing the timeline. Time is not a toy, and life can’t be manipulated to work in your favour (well, to an extent). Life will hopefully surprise us all – if we could go back and change it so that it worked out exactly how we wanted it to, we would never get to experience the strange, wonderful places that it might take otherwise take us.

Time is a great teacher but unfortunately it kills all its pupils.

Hector Berlioz

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe