To live outside the law, you must be honest.

– American proverb

People forget that Hunter Stockton Thompson was serious.

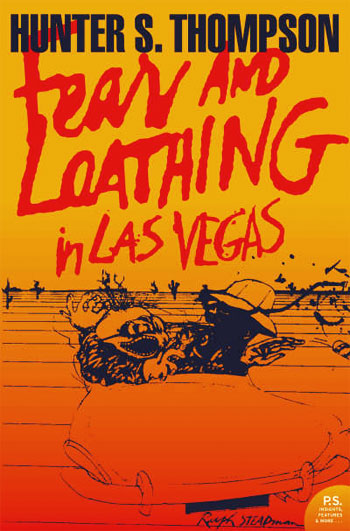

He devised gonzo journalism, pitching that in a phoney culture full of obfuscation and disengenuity, embedded and exaggerated subjectivity often stands a better chance of grasping at the truth than objective observation. His first three books traced the experience of trying to live outwith society in latter 20th century America (Hell’s Angels, the product of Thompson’s riding with the gang for a year before a dispute involving wife beating, dog kicking and who owed who beer ended his association with a stomping); a search for the American dream that found it waning since the defeat of the sixties’ counterculture (the drug-addled and Ralph Steadman-illustrated landmark novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas); and the search for some kind of hope in the resulting darkness (Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, tracing the Democratic Party’s efforts against President Nixon’s – ultimately successful – campaign for a second term).

He devised gonzo journalism, pitching that in a phoney culture full of obfuscation and disengenuity, embedded and exaggerated subjectivity often stands a better chance of grasping at the truth than objective observation. His first three books traced the experience of trying to live outwith society in latter 20th century America (Hell’s Angels, the product of Thompson’s riding with the gang for a year before a dispute involving wife beating, dog kicking and who owed who beer ended his association with a stomping); a search for the American dream that found it waning since the defeat of the sixties’ counterculture (the drug-addled and Ralph Steadman-illustrated landmark novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas); and the search for some kind of hope in the resulting darkness (Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, tracing the Democratic Party’s efforts against President Nixon’s – ultimately successful – campaign for a second term).

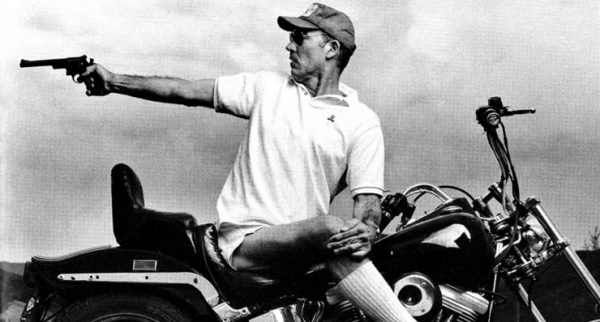

That the position of these books on bookshop shelves is so established can make people forget. Hunter Thompson wasn’t an author of books. He was a journalist. Both Fear and Loathing and Campaign Trail were originally serialised in Rolling Stone, where Hunter found his place on the masthead. 1979’s collection of Thompson journalism, The Great Shark Hunt (Gonzo Papers, vol. 1) – along with Bill Murray’s portrayal of him in Where The Buffalo Roam – cemented his reputation, both literary and chemical. He was an outlaw, besotted with drugs and explosives, pushing himself to the edge of danger to try and grapple the ugly truth. The problem was as these volumes established his fame, they scuppered the gonzo method. How to take an embedded approach when your presence makes each situation about you? Where could you go?

That the position of these books on bookshop shelves is so established can make people forget. Hunter Thompson wasn’t an author of books. He was a journalist. Both Fear and Loathing and Campaign Trail were originally serialised in Rolling Stone, where Hunter found his place on the masthead. 1979’s collection of Thompson journalism, The Great Shark Hunt (Gonzo Papers, vol. 1) – along with Bill Murray’s portrayal of him in Where The Buffalo Roam – cemented his reputation, both literary and chemical. He was an outlaw, besotted with drugs and explosives, pushing himself to the edge of danger to try and grapple the ugly truth. The problem was as these volumes established his fame, they scuppered the gonzo method. How to take an embedded approach when your presence makes each situation about you? Where could you go?

In the late sixties Thompson used Hell’s Angels royalties to buy a house in Woody Creek (outside Aspen, Colorado), to which he would increasingly retreat. Thompson’s next collection, Generation of Swine (Gonzo Papers, vol. 2), gathered his later ‘80s work. Hired as the media critic for the San Francisco Examiner, Hunter relocated briefly to San Francisco, only to return to Woody Creek, where most of these columns were written. A gigantic satellite dish was installed to give Hunter media access, only for Hunter to unpredictably cover political issues (like the Republican primaries and Iran-Contra scandal) almost in spite of himself, occasionally slipping into sports. Hunter remains an exhilarating stylist and Generation’s opening confession, of cribbing lines from hotel bibles’ book of Revelation when deadlines loomed, sets the tone. The Meese Report initiates a clampdown on pornography, AIDS puts an end to free love, Ronald Reagan takes office (later warning “This may be the generation that will face armageddon”) and Nancy Reagan advises everyone to just say no.

In the late sixties Thompson used Hell’s Angels royalties to buy a house in Woody Creek (outside Aspen, Colorado), to which he would increasingly retreat. Thompson’s next collection, Generation of Swine (Gonzo Papers, vol. 2), gathered his later ‘80s work. Hired as the media critic for the San Francisco Examiner, Hunter relocated briefly to San Francisco, only to return to Woody Creek, where most of these columns were written. A gigantic satellite dish was installed to give Hunter media access, only for Hunter to unpredictably cover political issues (like the Republican primaries and Iran-Contra scandal) almost in spite of himself, occasionally slipping into sports. Hunter remains an exhilarating stylist and Generation’s opening confession, of cribbing lines from hotel bibles’ book of Revelation when deadlines loomed, sets the tone. The Meese Report initiates a clampdown on pornography, AIDS puts an end to free love, Ronald Reagan takes office (later warning “This may be the generation that will face armageddon”) and Nancy Reagan advises everyone to just say no.

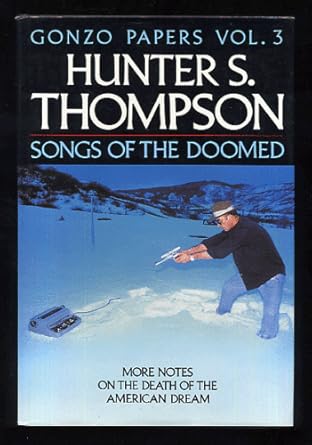

If Generation initiated allegations that Hunter was recycling past glories, Songs of the Doomed (Gonzo Papers, vol. 3) didn’t do much to refute them. A scrapbook of journalism, letters and extracts, from the fifties to the nineties, Songs features snippets of unpublished novels from the fifties (Prince Jellyfish), sixties (The Rum Diary) and eighties (The Silk Road), as well as Hunter’s recollections of Vietnam in the last days of the war. It also though, needlessly includes extracts from his first three books, already covered in The Great Shark Hunt. His coverage of the Pulitzer divorce trial gives him a real story to lay his ravenous teeth into, but there are also meandering forays into bull sperm auctions, driving strangers to Reno and his own legal difficulties.

If Generation initiated allegations that Hunter was recycling past glories, Songs of the Doomed (Gonzo Papers, vol. 3) didn’t do much to refute them. A scrapbook of journalism, letters and extracts, from the fifties to the nineties, Songs features snippets of unpublished novels from the fifties (Prince Jellyfish), sixties (The Rum Diary) and eighties (The Silk Road), as well as Hunter’s recollections of Vietnam in the last days of the war. It also though, needlessly includes extracts from his first three books, already covered in The Great Shark Hunt. His coverage of the Pulitzer divorce trial gives him a real story to lay his ravenous teeth into, but there are also meandering forays into bull sperm auctions, driving strangers to Reno and his own legal difficulties.

Returning Thompson to the political arena, Better Than Sex (Gonzo Papers, vol. 4) follows the 1992 Presidential campaign. Aside from a Rolling Stone sit-down with candidate Clinton and staying by his campaign HQ in the last days before the election (entailing a respectfully lurid portrayal of fellow political animal James Carville), BTS is again written from Woody Creek. The responses to some of his faxes show his continued access to significant players, but those unanswered give the awkward impression of someone painting themselves into a story from in front of their tv. A scrapbook of commentary and faxes, energy still pulses through the writing but there are messy digressions, loose ends, acknowledgements of getting too drunk. Hunter was always careful to avoid overt party-political allegiance (even if Watergate sealed Nixon representing all HST stood against). He’s not so much for Clinton, just dead-against George Bush. There’s a sense that unlike twenty years ago, this one isn’t really Thompson’s fight, that he can’t quite get as invested, and it fittingly ends with Hunter’s excoriating obituary of Nixon for Rolling Stone.

Returning Thompson to the political arena, Better Than Sex (Gonzo Papers, vol. 4) follows the 1992 Presidential campaign. Aside from a Rolling Stone sit-down with candidate Clinton and staying by his campaign HQ in the last days before the election (entailing a respectfully lurid portrayal of fellow political animal James Carville), BTS is again written from Woody Creek. The responses to some of his faxes show his continued access to significant players, but those unanswered give the awkward impression of someone painting themselves into a story from in front of their tv. A scrapbook of commentary and faxes, energy still pulses through the writing but there are messy digressions, loose ends, acknowledgements of getting too drunk. Hunter was always careful to avoid overt party-political allegiance (even if Watergate sealed Nixon representing all HST stood against). He’s not so much for Clinton, just dead-against George Bush. There’s a sense that unlike twenty years ago, this one isn’t really Thompson’s fight, that he can’t quite get as invested, and it fittingly ends with Hunter’s excoriating obituary of Nixon for Rolling Stone.

The late nineties saw the release from the vaults of such unreleased Thompson fiction as The Rum Diary and the short story collection Screwjack. The lucid, anecdotal memories of childhood and the air force that open Kingdom of Fear – Hunter’s first book (rather than collection) of new writing in almost two decades – suggests this could be what became of his oft-forecast autobiography, Polo is my Life. The content is largely autobiographical, but recollections are chronologically disordered, interspersed again with letters and photos. There’s a remarkable account of Hunter’s politicizing experience at the ’68 Democratic convention in Chicago, as well as his time as night manager at the Mitchell Brothers O’Farrell Theatre in San Francisco (‘the Carnegie Hall of public sex in America’; the subject of another unpublished novel, The Night Manager), his visiting Grenada just after the invasion and how he became a journalist. His time with the Hell’s Angels and bid for sheriff of Aspen are revisited yet again, but these aren’t the definitive accounts that might have been hoped for. The legal difficulties first mentioned in Songs of the Doomed are covered at length, Thompson; a search stemming from a bogus sexual assault charge becoming an issue threatening the right to privacy. We get accounts of test-driving Ducatis, visiting Cuba with Johnny Depp as the Bosnian war rages, and fighting cats in open-top cars. Hunter can’t seem to stop living the stream-of-consciousness on the page long enough to focus on the story to be told. Textual quirks such as capitalisation increase in frequency, as does use of Hunter’s trademark phrases (The fat is in the fire. The hog is out the tunnel. Res Ipsa Loquitur. And so much for all that, eh? Ho ho. Trust me, I understand these things. You bet. Mahalo. Selah.). What we’re left with is a field of loose ends. And the conclusion Hunter reaches in telling this story of his life? “I have the soul of a teenage girl in the body of an elderly dope fiend.” Ho ho.

The late nineties saw the release from the vaults of such unreleased Thompson fiction as The Rum Diary and the short story collection Screwjack. The lucid, anecdotal memories of childhood and the air force that open Kingdom of Fear – Hunter’s first book (rather than collection) of new writing in almost two decades – suggests this could be what became of his oft-forecast autobiography, Polo is my Life. The content is largely autobiographical, but recollections are chronologically disordered, interspersed again with letters and photos. There’s a remarkable account of Hunter’s politicizing experience at the ’68 Democratic convention in Chicago, as well as his time as night manager at the Mitchell Brothers O’Farrell Theatre in San Francisco (‘the Carnegie Hall of public sex in America’; the subject of another unpublished novel, The Night Manager), his visiting Grenada just after the invasion and how he became a journalist. His time with the Hell’s Angels and bid for sheriff of Aspen are revisited yet again, but these aren’t the definitive accounts that might have been hoped for. The legal difficulties first mentioned in Songs of the Doomed are covered at length, Thompson; a search stemming from a bogus sexual assault charge becoming an issue threatening the right to privacy. We get accounts of test-driving Ducatis, visiting Cuba with Johnny Depp as the Bosnian war rages, and fighting cats in open-top cars. Hunter can’t seem to stop living the stream-of-consciousness on the page long enough to focus on the story to be told. Textual quirks such as capitalisation increase in frequency, as does use of Hunter’s trademark phrases (The fat is in the fire. The hog is out the tunnel. Res Ipsa Loquitur. And so much for all that, eh? Ho ho. Trust me, I understand these things. You bet. Mahalo. Selah.). What we’re left with is a field of loose ends. And the conclusion Hunter reaches in telling this story of his life? “I have the soul of a teenage girl in the body of an elderly dope fiend.” Ho ho.

Hunter’s last volume was to be Hey Rube, a collection of his weekly columns for ESPN.com, where he had returned to his first journalistic calling, sportswriting, at the dawn of the new millennium. Ostensibly done with politics, events such as 9/11, the Iraq war and the behaviour of the ‘goofy child-President’ lead Hunter back again and again. Though he refuses to attend any games in person, sports is also covered however – NFL, NBA, NCAA, Nascar – and Hey Rube is awash with Thompson’s accompanying gambling ‘addiction’. Though titles may increasingly echo previous work, and the political outlook appear grim (“Compared to the Nazis we have in the White House now, Richard Nixon was a flaming liberal.”), the bitesize columns still speed along. Interested figures – Warren Zevon, Benicio Del Toro and Sean Penn among them – still make the pilgrimage to Woody Creek, to meet the wise man in his retreat. Hunter gets married (for the second time), has a hip replacement, but it’s when he becomes involved in the case of Lisl Auman that the sense of a real mission returns and the fire clearly still burns.

Hunter’s last volume was to be Hey Rube, a collection of his weekly columns for ESPN.com, where he had returned to his first journalistic calling, sportswriting, at the dawn of the new millennium. Ostensibly done with politics, events such as 9/11, the Iraq war and the behaviour of the ‘goofy child-President’ lead Hunter back again and again. Though he refuses to attend any games in person, sports is also covered however – NFL, NBA, NCAA, Nascar – and Hey Rube is awash with Thompson’s accompanying gambling ‘addiction’. Though titles may increasingly echo previous work, and the political outlook appear grim (“Compared to the Nazis we have in the White House now, Richard Nixon was a flaming liberal.”), the bitesize columns still speed along. Interested figures – Warren Zevon, Benicio Del Toro and Sean Penn among them – still make the pilgrimage to Woody Creek, to meet the wise man in his retreat. Hunter gets married (for the second time), has a hip replacement, but it’s when he becomes involved in the case of Lisl Auman that the sense of a real mission returns and the fire clearly still burns.

Drug use was a familiar feature of the sixties counterculture, but it can’t be the only enactment of it. When Thompson took his own life, on February 20th, 2005, the presumption was that all the excess had finally taken his toll, that his refusal to slow down had reaped its consequences; that living through a second term of the Bush administration was too grim a prospect; that the recluse had retreated so far he had nothing left. The presumption was that Hunter was defeated. In actual fact, Hunter’s two-line answer to a suicide note (entitled ‘Football Season Is Over’) is one of the most lucid and powerful moments of writing in his latter career. People forget that Thompson had already seen the defeat, before he was even able to fully process it in the conclusion of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Having witnessed the collapse of the counterculture he’d invested in, Hunter kept its flame burning. In the spirit of personal freedom, chemical excess, justice and equality, creativity and good fun, through the corruption of the seventies, the greed of the eighties, the apathy of the nineties and into the “first horrible years of our new Century”. He did it as long as he could enjoy it, and then he stopped. He did it to show others another possibility. And the fact that his ashes were fired from a canon, at the top of a 153ft tower of the gonzo logo – all funded by his good friend Johnny Depp, with attendees including John Kerry, Jack Nicholson and Sean Penn – just shows how firmly that flame spread. That is all ye know, and all ye need know. You bet.

Drug use was a familiar feature of the sixties counterculture, but it can’t be the only enactment of it. When Thompson took his own life, on February 20th, 2005, the presumption was that all the excess had finally taken his toll, that his refusal to slow down had reaped its consequences; that living through a second term of the Bush administration was too grim a prospect; that the recluse had retreated so far he had nothing left. The presumption was that Hunter was defeated. In actual fact, Hunter’s two-line answer to a suicide note (entitled ‘Football Season Is Over’) is one of the most lucid and powerful moments of writing in his latter career. People forget that Thompson had already seen the defeat, before he was even able to fully process it in the conclusion of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Having witnessed the collapse of the counterculture he’d invested in, Hunter kept its flame burning. In the spirit of personal freedom, chemical excess, justice and equality, creativity and good fun, through the corruption of the seventies, the greed of the eighties, the apathy of the nineties and into the “first horrible years of our new Century”. He did it as long as he could enjoy it, and then he stopped. He did it to show others another possibility. And the fact that his ashes were fired from a canon, at the top of a 153ft tower of the gonzo logo – all funded by his good friend Johnny Depp, with attendees including John Kerry, Jack Nicholson and Sean Penn – just shows how firmly that flame spread. That is all ye know, and all ye need know. You bet.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe