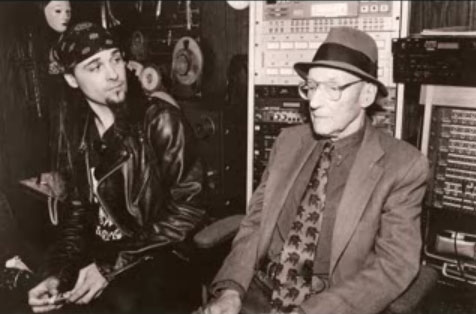

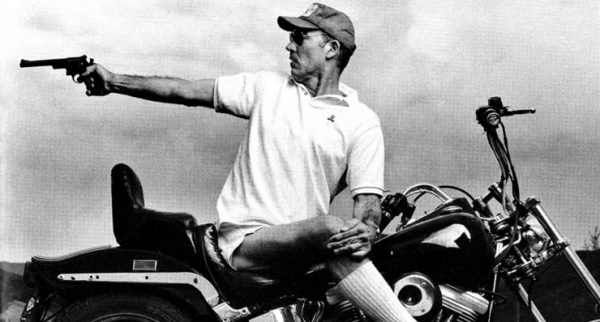

Alain Jourgensen was just another fresh-faced, Cuban-American frontman of a synth band until Ministry struck their true character with third album The Land Of Rape And Honey. On Land, and its more guitar-heavy sister The Mind is a Terrible Thing to Taste, Ministry’s industrial music uses synthesisers, samplers and vocal distortion to create rock aggression, combining disjointed rhythms, bludgeoning repetition and blasts of noise with bona fide tunes like ‘Thieves’ and ‘Stigmata’. Uncharacteristically for a late-eighties ‘rock star’, Jourgensen started associating with aging counterculture icons like the grand magus William S. Burroughs and former LSD shaman (and, in Hunter S. Thompson’s words, ‘treacherous sellout’) Timothy Leary. And Ministry’s sound continued to evolve as their success grew, from the big, Lollapalooza-ready alt-rock guitars of Psalm 69 to the dissolute chaos of the huge-sounding Filth Pig and its follow-up The Dark Side of the Spoon – both of which played up to Al’s burgeoning reputation as a drug bucket (see, for example, the rollicking mockery of celebrity drug confessions in ‘Step’).

Alain Jourgensen was just another fresh-faced, Cuban-American frontman of a synth band until Ministry struck their true character with third album The Land Of Rape And Honey. On Land, and its more guitar-heavy sister The Mind is a Terrible Thing to Taste, Ministry’s industrial music uses synthesisers, samplers and vocal distortion to create rock aggression, combining disjointed rhythms, bludgeoning repetition and blasts of noise with bona fide tunes like ‘Thieves’ and ‘Stigmata’. Uncharacteristically for a late-eighties ‘rock star’, Jourgensen started associating with aging counterculture icons like the grand magus William S. Burroughs and former LSD shaman (and, in Hunter S. Thompson’s words, ‘treacherous sellout’) Timothy Leary. And Ministry’s sound continued to evolve as their success grew, from the big, Lollapalooza-ready alt-rock guitars of Psalm 69 to the dissolute chaos of the huge-sounding Filth Pig and its follow-up The Dark Side of the Spoon – both of which played up to Al’s burgeoning reputation as a drug bucket (see, for example, the rollicking mockery of celebrity drug confessions in ‘Step’).

The difference between the fairly stationary, clean-cut Jourgensen fronting Ministry in the post-Mind live set In Case You Didn’t Feel Like Showing Up, and the dreadlocked, striding gonzo figure leading them through the Filth Pig set Sphinctour is striking. As much fuss as Johnny Depp made of basing Jack Sparrow on good old Keef, there’s undeniably something to Jello Biafra’s comparison of Captain Jack with a certain industrial frontman.

The difference between the fairly stationary, clean-cut Jourgensen fronting Ministry in the post-Mind live set In Case You Didn’t Feel Like Showing Up, and the dreadlocked, striding gonzo figure leading them through the Filth Pig set Sphinctour is striking. As much fuss as Johnny Depp made of basing Jack Sparrow on good old Keef, there’s undeniably something to Jello Biafra’s comparison of Captain Jack with a certain industrial frontman.

But then, the band’s contract with Warner Bros expired and bassist, foil and Neil Gaiman-lookalike Paul Barker departed, citing ‘musical differences’ and possibly just having had his fill. The band lay dormant for a few years, before limping back into view with the dry and blustery hammering of the palindromically titled Animositisomina (of which a surprisingly straight cover of Magazine’s ‘The Light Pours Out Of Me’ is a highlight). Uncle Al does not quit however. He is incapable. Parallel to Ministry, Jourgensen operated (with many of the same staff) the more beats-orientated Revolting Cocks, as well as collaborations with Dead Kennedys’ Jello Biafra (Lard) and Fugazi’s Ian MacKaye (Pailhead), among others. Al just needed a mission to drag him back.

But then, the band’s contract with Warner Bros expired and bassist, foil and Neil Gaiman-lookalike Paul Barker departed, citing ‘musical differences’ and possibly just having had his fill. The band lay dormant for a few years, before limping back into view with the dry and blustery hammering of the palindromically titled Animositisomina (of which a surprisingly straight cover of Magazine’s ‘The Light Pours Out Of Me’ is a highlight). Uncle Al does not quit however. He is incapable. Parallel to Ministry, Jourgensen operated (with many of the same staff) the more beats-orientated Revolting Cocks, as well as collaborations with Dead Kennedys’ Jello Biafra (Lard) and Fugazi’s Ian MacKaye (Pailhead), among others. Al just needed a mission to drag him back.

On the following year’s Houses of the Molé, with its Illuminati conspiracy theorist-taunting cover, Ministry clearly relocated its mojo, love of pun titles and sense of purpose. With guitars heavier than ever, Ministry entered their new phase a ragged band of drunken, tattooed thrash metal cowboys. With Barker gone, and fame (or at least infamy) attained, Uncle Al’s personality was front and centre. Rigor Mortis guitarist and longtime Jourgensen collaborator Mike Scaccia took up position as Al’s foil, and supplier of thrash metal joie de vivre, but who’d really put the lead back in Al’s pencil was evident from the fact that, aside from Molé‘s breakneck opener ‘No W’, all titles begin with the same letter: W. As was the custom of the day (see also, for example, Xzibit’s ‘State of the Union’), Molé begins with samples of the ‘goofy child-President’ – here placed over Carl Orff’s ‘O Fortuna’, to really set the tone – and he reappears throughout. Was it the information age making sound recordings so easily accessible and manipulable, or just that he lent himself so easily to quotation? Molé as a whole is a state of the union for post-9/11 life under the Bush administration: absurd and threatening, glimpsing bizarre events as it gallops towards the brink. ‘Worm’ is stamped across the end of it like a giant, harmonica-strung dayglo acid smiley.

On the following year’s Houses of the Molé, with its Illuminati conspiracy theorist-taunting cover, Ministry clearly relocated its mojo, love of pun titles and sense of purpose. With guitars heavier than ever, Ministry entered their new phase a ragged band of drunken, tattooed thrash metal cowboys. With Barker gone, and fame (or at least infamy) attained, Uncle Al’s personality was front and centre. Rigor Mortis guitarist and longtime Jourgensen collaborator Mike Scaccia took up position as Al’s foil, and supplier of thrash metal joie de vivre, but who’d really put the lead back in Al’s pencil was evident from the fact that, aside from Molé‘s breakneck opener ‘No W’, all titles begin with the same letter: W. As was the custom of the day (see also, for example, Xzibit’s ‘State of the Union’), Molé begins with samples of the ‘goofy child-President’ – here placed over Carl Orff’s ‘O Fortuna’, to really set the tone – and he reappears throughout. Was it the information age making sound recordings so easily accessible and manipulable, or just that he lent himself so easily to quotation? Molé as a whole is a state of the union for post-9/11 life under the Bush administration: absurd and threatening, glimpsing bizarre events as it gallops towards the brink. ‘Worm’ is stamped across the end of it like a giant, harmonica-strung dayglo acid smiley.

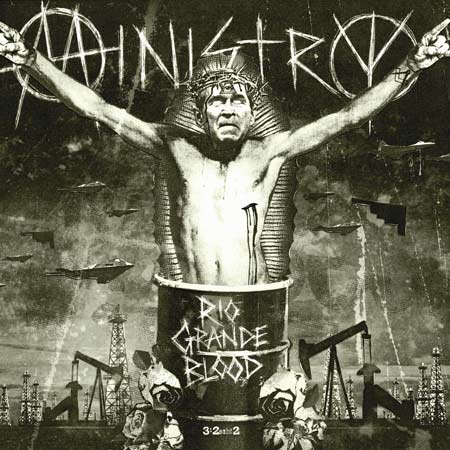

The feeling of Ministry firing at full force is something akin to standing on a leyline, and so it is on Rio Grande Blood (named after ZZ Top’s Rio Grande Mud). A muscular, disjointed thrash metal whirlwind of 9/11 conspiracy theories, W samples and ludicrous humour, Rio Grande sees Al’s ire at the Bush administration reaching full tilt on tracks like ‘Ass Clown’, peaking with pounding closer ‘Khyber Pass’. The cult of personality around Al may have kept growing – and his lyrical focus may have added Al Jazeera to his list of aliases – but Rio Grande’s furious vocals are the most direct he’s ever sounded.

The feeling of Ministry firing at full force is something akin to standing on a leyline, and so it is on Rio Grande Blood (named after ZZ Top’s Rio Grande Mud). A muscular, disjointed thrash metal whirlwind of 9/11 conspiracy theories, W samples and ludicrous humour, Rio Grande sees Al’s ire at the Bush administration reaching full tilt on tracks like ‘Ass Clown’, peaking with pounding closer ‘Khyber Pass’. The cult of personality around Al may have kept growing – and his lyrical focus may have added Al Jazeera to his list of aliases – but Rio Grande’s furious vocals are the most direct he’s ever sounded.

For all the grand claims made by its opener ‘Let’s Go’ (“Let’s go for the end of reality/Let’s go for total insanity!”) The Last Sucker, the final instalment of Ministry’s W trilogy (with pop-up gatefold showing the band at The Last Supper), is a darker, overcast affair. A sense of lost hope and lack of escape prevails, the grind only broken by frantic bursts like ‘Death and Destruction’. A factor might be that at this point Al was coughing up blood due to rupturing ulcers in his oesophagus, leading him to declare this would be the final Ministry album. The distorted Jourgensen roar at times still sounds like it could swallow planets though, and the gesture of using half of a ten-minute finale to sample, clearly and at length, President Eisenhower’s ‘military-industrial complex’ farewell speech is an incredible parting gesture.

For all the grand claims made by its opener ‘Let’s Go’ (“Let’s go for the end of reality/Let’s go for total insanity!”) The Last Sucker, the final instalment of Ministry’s W trilogy (with pop-up gatefold showing the band at The Last Supper), is a darker, overcast affair. A sense of lost hope and lack of escape prevails, the grind only broken by frantic bursts like ‘Death and Destruction’. A factor might be that at this point Al was coughing up blood due to rupturing ulcers in his oesophagus, leading him to declare this would be the final Ministry album. The distorted Jourgensen roar at times still sounds like it could swallow planets though, and the gesture of using half of a ten-minute finale to sample, clearly and at length, President Eisenhower’s ‘military-industrial complex’ farewell speech is an incredible parting gesture.

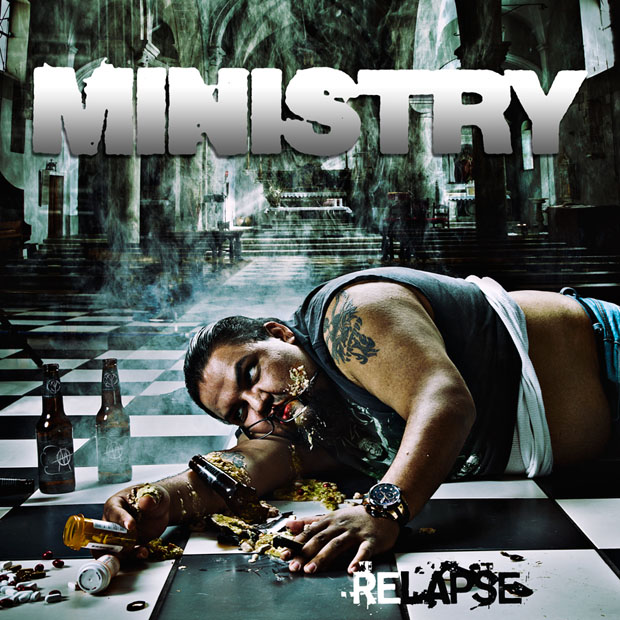

But again. Uncle Al doesn’t quit. Live, remix and compilation Ministry releases followed. RevCo were remobilised and, while significantly outsourced to new members, the howling and hammering of songs like ‘Abundant Redundancy’ still show an outlet for Jourgensenian genius. And then there was Bikers Welcome Ladies Drink Free, by Buck Satan and the 666 Shooters. Al’s bizarrely brilliant country album. Not quite as incongruous as it sounds, as Ministry’s cowboy hats weren’t just affectation. Since the early nineties, Al had been based in a compound near El Paso, Texas (which he describes as “a city of outlaws … nothing but bikers and outlaws”), meaning the W trilogy originated in George’s home state. Al had frequently professed a love of country and shown his softer side in instances like Ministry’s appearance at Neil Young’s Bridge School Benefit, performing an acoustic Grateful Dead cover in fine voice. It was while working up material for Buck Satan that Scaccia persuaded Al the heavier material they came up with had an obvious calling: another Ministry album. And thus, Relapse was born. If Al’s appearance at this point could be said to reflect a Ministry song, it would be their early-‘80s goth club hit ‘Everyday is Halloween’, sporting top hat, dreads, facial piercings and a saturation of tattoos. Shuffling through the Relapse ‘making of’ videos, drunk and beskirted, he looks like a wizened old traveller woman, about to gleefully tell someone their bad fortune.

But again. Uncle Al doesn’t quit. Live, remix and compilation Ministry releases followed. RevCo were remobilised and, while significantly outsourced to new members, the howling and hammering of songs like ‘Abundant Redundancy’ still show an outlet for Jourgensenian genius. And then there was Bikers Welcome Ladies Drink Free, by Buck Satan and the 666 Shooters. Al’s bizarrely brilliant country album. Not quite as incongruous as it sounds, as Ministry’s cowboy hats weren’t just affectation. Since the early nineties, Al had been based in a compound near El Paso, Texas (which he describes as “a city of outlaws … nothing but bikers and outlaws”), meaning the W trilogy originated in George’s home state. Al had frequently professed a love of country and shown his softer side in instances like Ministry’s appearance at Neil Young’s Bridge School Benefit, performing an acoustic Grateful Dead cover in fine voice. It was while working up material for Buck Satan that Scaccia persuaded Al the heavier material they came up with had an obvious calling: another Ministry album. And thus, Relapse was born. If Al’s appearance at this point could be said to reflect a Ministry song, it would be their early-‘80s goth club hit ‘Everyday is Halloween’, sporting top hat, dreads, facial piercings and a saturation of tattoos. Shuffling through the Relapse ‘making of’ videos, drunk and beskirted, he looks like a wizened old traveller woman, about to gleefully tell someone their bad fortune.

If the finale of Last Sucker was an emphatic ending though, then the first two minutes of ‘Ghouldiggers’ is also a fairly charismatic way of reneging on your retirement. As is joyously shouting ‘I’MNOTDEADYETI’MNOTDEADYET- I’MNOTDEADYETI’MNOTDEADYET!!’ Ministry are brawnier on Relapse, with a lower centre of gravity, but clearly reenergised. Arriving under the Obama administration, it isn’t as thematically cohesive as the W Trilogy (drone strikes, Prism, penalising whistleblowers and the continued existence of Gitmo having yet to provoke the ire of Al). It acts as a scrapbook encompassing everything from cover versions and the music industry (‘Ghouldiggers’) to democracy (‘Get Up, Get Out And Vote’) and the Bin Laden assassination (‘Double Tap’). There are also more directly personal lyrics. “I pissed away over ten million dollars/On dope and crack” Al states bluntly on the breakneck ‘Freefall’. And if lyrics like the bellowed “I’m filthy rich and I’m horny/But you just fucking bore me!” are more in line with the Uncle Al caricature than the calibre we’ve come to expect from Al’s warped and edgy mind, he does at least sound in unfeasibly rude health.

If the finale of Last Sucker was an emphatic ending though, then the first two minutes of ‘Ghouldiggers’ is also a fairly charismatic way of reneging on your retirement. As is joyously shouting ‘I’MNOTDEADYETI’MNOTDEADYET- I’MNOTDEADYETI’MNOTDEADYET!!’ Ministry are brawnier on Relapse, with a lower centre of gravity, but clearly reenergised. Arriving under the Obama administration, it isn’t as thematically cohesive as the W Trilogy (drone strikes, Prism, penalising whistleblowers and the continued existence of Gitmo having yet to provoke the ire of Al). It acts as a scrapbook encompassing everything from cover versions and the music industry (‘Ghouldiggers’) to democracy (‘Get Up, Get Out And Vote’) and the Bin Laden assassination (‘Double Tap’). There are also more directly personal lyrics. “I pissed away over ten million dollars/On dope and crack” Al states bluntly on the breakneck ‘Freefall’. And if lyrics like the bellowed “I’m filthy rich and I’m horny/But you just fucking bore me!” are more in line with the Uncle Al caricature than the calibre we’ve come to expect from Al’s warped and edgy mind, he does at least sound in unfeasibly rude health.

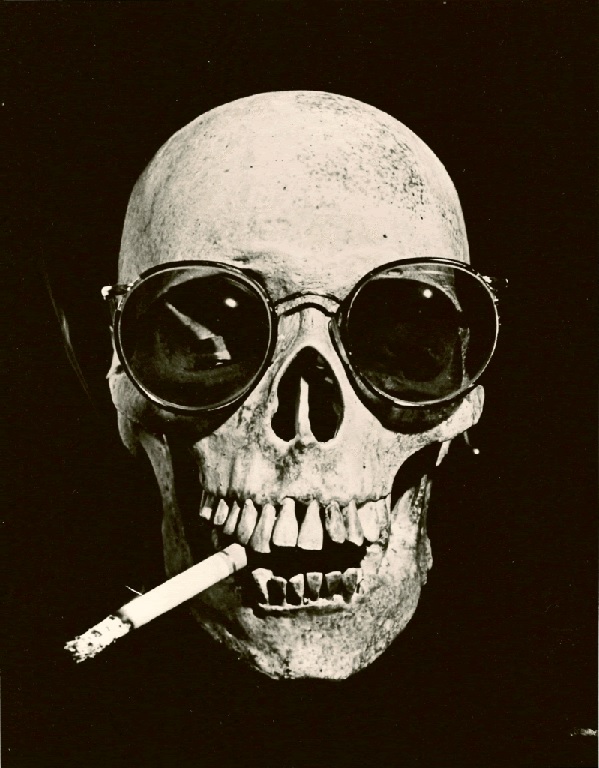

And so ended the last Ministry album, the final Ministry tour. People travel to Al’s studio/label compound 13th Planet to visit him, as they travelled to visit with Burroughs and Thompson. Al cemented his larger-than-life persona with the release of his all-out autobiography, and is even becoming a comic book character. Ministry was over. Except… Shortly after finishing recording guitar parts for Ministry, Mike Scaccia took the stage with Rigor Mortis, collapsed, and died of undiagnosed heart disease at 47. In honour of Mikey, the ‘final’ Ministry album, From Beer to Eternity, arrives this year, and any thoughts that Al’s personality or the humour of Ministry might have been reined in by the circumstances are answered by the cover:

And so goes the last Ministry album. Probably. Except for perhaps the next one. Maybe. Even if this really is it for Ministry, Al Jourgensen – the man behind Ministry, Revolting Cocks, Buck Satan, Lard, Pailhead and many others – won’t quit music. He’s incapable. There’s already been talk of collaboration projects with Ministry disciple Trent Reznor and (no, really) Lil Wayne. Making music is coded in his DNA, like so much other unusual behaviour. Al doesn’t try to be different. He just is. And so long as the mics at 13th Planet are on, and his body incredibly continues to refuse death, Uncle Al will continue to preach his wisdom and drink his wine, and the weird will have at least one place on earth to keep its flame. Mahalo.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Great article! I don’t know what more to say than that, it was a very enjoyable read created by someone who is obviously a fan. 😀 Just as myself.