‘It’s like everyone tells a story about themselves inside their own head. Always. All the time. That story makes you what you are. We build ourselves out of that story.’

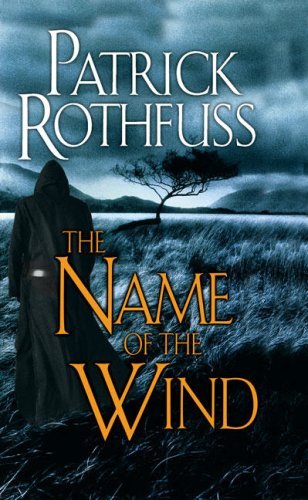

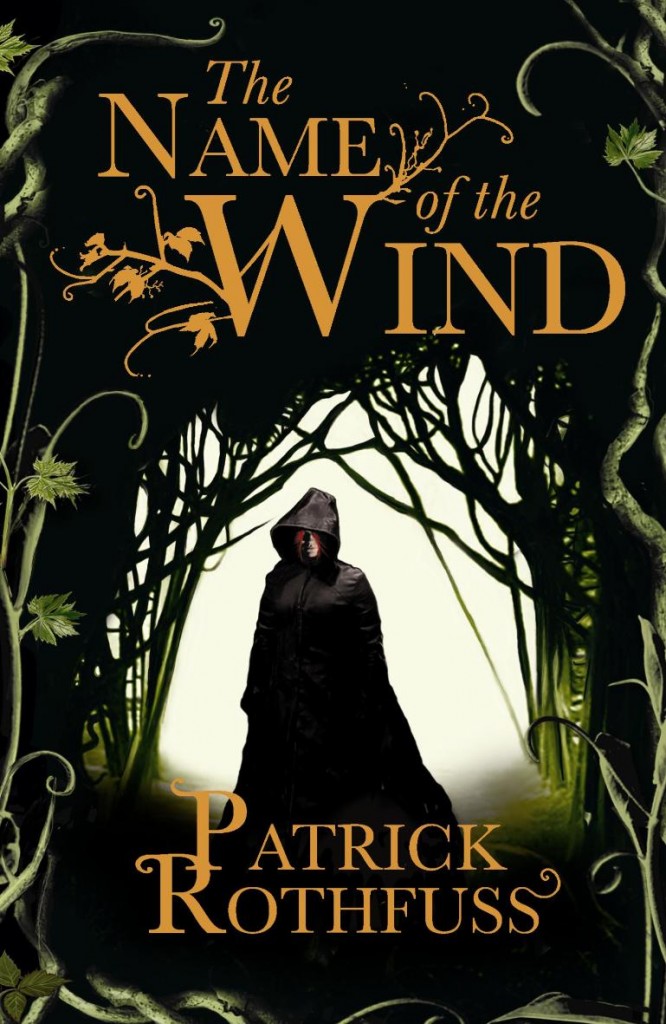

Over the past year or so I have been exploring the fantasy genre – a genre I had previously left fairly untouched when it came to my reading. One book that was recommended very early to me was The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss. I was curious about it, but it didn’t pique my interest quite as much as some of the others, leading it to fall further down the ‘to read’ pile.

When I did eventually get to it, I started reading directly after finishing the epic Words of Radiance… this was a mistake. I was riding sky high on Sanderson’s amazing world. The shift into Rothfuss’s was more than a little jarring – and disappointing. The magic system was very limited in comparison (and a little too similar to Le Guin’s) and the characters were far fewer in number and nowhere near as well crafted.

The beginning was very slow, and I found myself working hard to get to the 40% mark. Having said that, once I passed that mark, I loved it. I eagerly read to the end from there. Perhaps this is something I could mark down as teething problems with a debut novel, but I think some of the issues with the opening could easily have been fixed by a good edit.

This novel is consistently listed amongst the best fantasy novels of recent years. While I semi-enjoyed the overall experience, I have to question why people love it quite so much?

Plot

A small town innkeeper is more than he at first appears. The roads to the town are dangerous – full of thieves, deserters, and monsters. A local man is attacked by a terrifying, demon-like creature, prompting Kvothe to step out of his innkeeper guise and protect those around him. While fighting the Scrael, Kvothe saves a famous Chronicler who insists on hearing the story of the ‘Kvothe the Kingkiller’.

A small town innkeeper is more than he at first appears. The roads to the town are dangerous – full of thieves, deserters, and monsters. A local man is attacked by a terrifying, demon-like creature, prompting Kvothe to step out of his innkeeper guise and protect those around him. While fighting the Scrael, Kvothe saves a famous Chronicler who insists on hearing the story of the ‘Kvothe the Kingkiller’.

Kvothe gives in to Chronicler’s relentless requests and tells his story, from his days as a travelling performer with his family, his time as a homeless orphan on the streets of Tarbean, and his eventual acceptance into the University.

The rules of writing

All writers know any number of writing rules. And while we know that these are really more like guidelines than rules, as Chuck Wendig says, these are things that are just hard to do well. Being aware that rules are there to be broken (for innovative and fresh stories), there is one rule – or guideline – that I really recommend writers keep in mind, which applies to this novel in particular. That is: start as far into things as possible. Avoid heavy exposition, make the reader be a little confused (but not utterly lost), have them asking questions, drive them forward with the motion of the story and the desire to know what happens.

At first you get taken into a story that does dump you right in the middle of things. Great! But only a few chapters in – when you are warming up to the characters and starting to develop interesting questions about what might happen – the author pulls the rug out from under you and drags you way, way back to the beginning. It took me a long while to work out why I should give a damn and it felt a little bit too expositional for my liking. Sure, I understand that his time living on the streets greatly impacted Kvothe’s life, but I didn’t need quite so much of it. None of it moves the plot along and the characterization it adds isn’t enough of a pay-off.

Give us a climax!

Throughout the novel I was curious as to what kind of epic battle or climactic tension would grow for the ending. Well here’s a spoiler: there isn’t one. There is no climax. Nothing to keep you on the edge of your seat, staying up hours past your bedtime to get the book finished. There is also a general lack of major struggle for the protagonist. His biggest issues are poverty and teenage rivalries (Ambrose, Kvothe’s rival at the University, is lazily characterized, relying heavily on stereotypes of spoilt rich kids rather than giving him an actual personality or believable motivations). That hardly makes for an epic or terribly entertaining fantasy tale.

Throughout the novel I was curious as to what kind of epic battle or climactic tension would grow for the ending. Well here’s a spoiler: there isn’t one. There is no climax. Nothing to keep you on the edge of your seat, staying up hours past your bedtime to get the book finished. There is also a general lack of major struggle for the protagonist. His biggest issues are poverty and teenage rivalries (Ambrose, Kvothe’s rival at the University, is lazily characterized, relying heavily on stereotypes of spoilt rich kids rather than giving him an actual personality or believable motivations). That hardly makes for an epic or terribly entertaining fantasy tale.

Early on we are made aware that there are creatures akin to ‘demons’ (Scrael and the Fae) in the world, then we are introduced to the Chandrian. While it is a great tool to use the character’s own ignorance as a way for the reader to learn more about something in the world, we actually expect to get answers by the end of it. By the end of The Name of the Wind I felt my knowledge of ‘the big bad’ was barely more than when I started reading. So why give us that entire story? It felt like the first third of a novel, not the first book of a series. Even books in a series need to give answers and a climactic moment in each book.

Verdict: Despite all its flaws, The Name of the Wind is enjoyable. But it is not groundbreaking or particularly amazing. One for the hardcore fantasy genre fans, but best avoided by the tourists.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe