“It’s so easy to talk about a drag queen – but it’s so difficult to be one.”

– Alexis Mateo (season 3)

Jonathan Ross recently revealed that he’s bought the rights to develop, with Jodie Harsh, a UK version of the reality tv show RuPaul’s Drag Race – describing it as ‘fabulous art’. With reality tv having become such a ubiquitously cheap source of endless, artless entertainment – with minimal scripting, non-professional casts – why should you care? Because Drag Race is one of the greatest things to have crossed the small screen in recent years.

Hosted by RuPaul – acclaimed drag queen, supermodel, singer, talk show host and ordained minister – Drag Race is America’s Next Top Model rebuilt in her image. Each season, a group of drag queens compete in challenges and walk the runway in hopes of being crowned America’s next drag superstar. Ru’s love of wordplay (innuendos, puns, drag slang) saturates the show and, along with the fixed format, makes it a breeding ground for catchphrases. (It took till season 4 for someone to point out to me that the show’s mantra of qualities a drag superstar needs – Charisma, Uniqueness, Nerve and Talent – is an acronym.) The cheapness of the format also plays as kitsch – Ru incessantly mentioning the sponsors, or hawking her new album enough to make ‘now available on iTunes’ another show catchphrase.

Levels to this shit

Rebecca

So it’s a reality tv show, but the contestants are men in dresses. Simple, right? Not really. The first thing to get clear is the difference between drag queens and transvestites and transsexuals. For drag queens, drag is a job. When they don drag, queens often – like rappers, like pornstars – adopt stage names, and distinct (and extreme) personas. In season 1, a short, demure Hispanic man can transform into the leggy, bitchy beauty, Rebecca Glasscock. These are gay men who don’t wear women’s clothes in their everyday lives and don’t (with a couple of later exceptions) want to actually become women. And what’s drag’s place in the gay community? Queens talk of having to hide their drag and sequins when bringing someone home, to avoid revealing their profession. The show also emphasises though the tight circles formed in drag’s niche scene: contestants across the series are frequently already friends, colleagues, couples or enemies.

And then there are the divisions within drag. Between those who serve the fishy and flawless look of beauty pageants, and the character-based, alternative looks of ‘comedy queens’ – a division exemplified by season 4’s feud between ‘tired-ass showgirl’ Phi Phi O’Hara and self-proclaimed ‘punk rock sex clown’ Sharon Needles. Between the kitschy camp of regional styles and metropolitan high-fashion couture. Between those who pad their figure, or use rubber breast plates, and those who work with just their own body’s femininity. And then there are looks dealing in androgyny (looking neither wholly masculine nor feminine) and genderfuck (with signifiers of both genders). For clarity, there’s Tatianna’s succinct definition: ‘As long as I have a dick between my legs and wig on my head, I’m a drag queen’.

Some girls are bigger than others

Placing so much emphasis on physicality, Drag Race doesn’t scrimp on variety in its contestants. Queens come from right across the United States: black, white, Hispanic, Asian; young, older, tall, short, big or practically skeletal. You see the range when petit ladyboy Ongina is almost engulfed by Bebe Zahara Benet’s vast afro wig. Anyone mistaking this for tokenism though should proceed straight to season 4’s Latrice Royale. Chunky yet funky, large yet very much in charge, this 39 year old ex-con in bejewelling makeup is very much a force to be reckoned with. Whether taking the queens to church with a chorus of ‘Jesus is a biscuit’ or dressing them down for unbecoming behaviour till they hang their heads in shame, Latrice – as often happens on the show – renders size secondary to personality.

You betta werk!

Win America’s Next Top Model, embark on a modelling career. But what do drag queens actually do? Many queens have day jobs – dancers, models, makeup artists and choreographers, female impersonators and Vegas showgirls – but Drag Race demands many talents. Each week, the queen to be eliminated is determined by the bottom two lipsyncing for their lives, but queens also have to model, style themselves (outfit, makeup and wigs), design and sew outfits, impersonate celebrities, perform standup and sing, all while being an endearing ambassador for drag. And then there are the more particular skills, like ‘reading’ other queens (evaluating weaknesses and calling them) and death drops.

Pretty isn’t everything

With so much expected, more ‘fishy’ (that is, convincingly feminine) queens like Rebecca, Tatianna and Courtney Act are often criticized for resting on pretty. Female impersonation is an aspect of drag, but not the extent of it. Drag’s edge isn’t that these men could be mistaken for women, nor looking like men in dresses. It’s that queens are never wholly one thing or the other, but something you haven’t seen before. Drag is more performative, over the top and camply irreverent: huge hair, dramatic makeup and characters larger than life. Drag never takes itself too seriously, laughing at itself as much as everyone else; constantly full of innuendo and resolutely non-PC.

Drag pre-empts the inevitable criticisms by serving itself first. The best looks are sickening, with a face beat to make you gag. Queens’ kiki is full of ‘bitch’ this, ‘cunt’ that and (as a camping of ‘retarded’) ‘leotarded’. Asked why she started insulting others less midway through season 2, the fabulously foul-mouthed Raven attributes it to the realisation that ‘the next drag superstar needs to be, basically, not such a wretched cunt’. These terms can be of affection as much as insult, and the complexity of drag’s language is illustrated by Nina Flowers, explaining calling everyone ‘loca’:

“The meaning of the word loco, or loca, means crazy. But in the gay Latin community, loca means queen. Or, if some straight guy screams at you ‘Look at that loca!’, he’s saying it in a mean way so ‘Oh, look at that queer’. But if a friend of you tells you like ‘Loca…’, it’s like saying ‘girl’.”

I’m the fucking future of drag

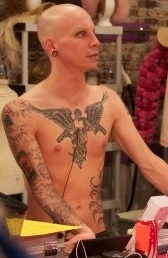

Through all their differences, one thing the queens share is experience of intolerance; in school, on the street or from their own families. They may play fun and vulnerable but when Mike – a muscular, retired cop grandfather being made-over for the episode – misjudges starting some ‘drag queen drama’ with Chad Michaels, we see a skinny, 40-year-old man – who’s had plastic surgery to resemble Cher – unleashing an impressively furious, defensive barrage of trash talk. When the very zen queen The Princess removes her drag, it reveals her epic chest tattoo of an angel, with two pistols drawn on the world.

Sharon Needles’ star quality was obvious even before she appeared as a blood-drooling zombie for her first runway appearance. Flattered by The Princess for her ‘meth look’, even out of drag Needles’ outfits are entertaining: from her halloween pumpkin T and skintight shiny leopard-print trousers, to ironically-sported, skinny-fit campaign t-shirts for Nixon and Palin. A drag peformance artist who regularly puts torn Bible pages in a blender of vodka, before spitting them over the audience. It’s hard to think of anyone whose endorsement they would have wanted less. Not just a honed aesthetic and encyclopedia of trashy pop culture references, Needles used her appearance to carry the message that not only can you be a drag queen, you can be any kind of anything you want. From the laughing stock of her local drag scene in Pittsburgh, the city named June 12th Sharon Needles Day in 2012.

The following season saw another adorable underdog, in Needles’ then-boyfriend, Alaska Thunderfuck. With his langurous Will Self drawl and babybird, just-fell-out-the-nest demeanour out of drag, watching Lasky through the season had the endearing quality of watching a plane crashing that just might make it over the finish line before hitting the ground. Another queen of unconventional style is Jinkx Monsoon, ‘Seattle’s premier Jewish narcoleptic drag queen’. Fending off sleep and dismissal from other queens, for her old-fashioned glamour lacking sex appeal, this theatrical queen demonstrates genuinely remarkable determination in the face of adversity.

Don’t fuck it up

Phi Phi

One of Drag Race’s greatest lessons has nothing to do with gender or clothing. As series progress a theme recurs of queens becoming too focussed on beating specific rivals, rather than being the best queen they can be. Appropriately for a show that awards a Miss Congeniality title every season, the skewed focus of grudges frequently becomes queens’ undoing.

Drag Race’s irreverent queenery hasn’t escaped criticism , and not just from expected sources. Needles’ satirical performance art has drawn accusations of racism, while the show itself has been criticized for contestants’ use – or appropriation of – racial stereotypes, and was recently accused of transphobia. Drag deconstructs what society holds to be feminine, demonstrating gender’s construction, but the presence of female judges each week tempers what could be an awkward situation; gay men together, dressing as women and laughing about femininity. Several show challenges cleverly investigate gender norms, whether having the queens come face to face with a group of – distinctly masculine – female professional fighters, or having the queens dress as both the bride and groom for a wedding photo (Tatianna making a particularly unconvincing groom).

Drag Race’s irreverent queenery hasn’t escaped criticism , and not just from expected sources. Needles’ satirical performance art has drawn accusations of racism, while the show itself has been criticized for contestants’ use – or appropriation of – racial stereotypes, and was recently accused of transphobia. Drag deconstructs what society holds to be feminine, demonstrating gender’s construction, but the presence of female judges each week tempers what could be an awkward situation; gay men together, dressing as women and laughing about femininity. Several show challenges cleverly investigate gender norms, whether having the queens come face to face with a group of – distinctly masculine – female professional fighters, or having the queens dress as both the bride and groom for a wedding photo (Tatianna making a particularly unconvincing groom).

Drag is an art form

The most striking thing about Drag Race is the transformation between the men and glamorous, technicolour confections they become. Through styling an painting, queens create an entirely new person – an exaggerated more than a person – from scratch, embodying personal expression and self-sufficiency, transforming themselves into living art.

Those who say there’s a ‘gay agenda’ at work (‘They want the same rights as every other human being!’) in the case of RuPaul’s Drag Race would be absolutely right. And so is Ru. Through the contestants, as well as some of the challenges, Drag Race raises issues from gay marriage, plastic surgery and living with AIDS to the Stonewall riots, serving under ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ and transgender transitioning. With reality tv frequently accused of being an exploitative freakshow – and with drag queens arguably easier to cast in such a light than most – Drag Race is a platform to make people familiar with not just the abstract issues, but those affected by them every day. Ru jokes of Drag Race ‘bringing families together’ but with several contestants’ families, giving them an opportunity to see what their children actually do, this is clearly the case. And it’s likely true on a broader scale.

With spin-off series, like RuPaul’s Drag U and All Stars Drag Race, a forthcoming seventh season and the possible UK spinoff, Drag Race continues bringing fierce fabulousness and questions of gender to the world, through entertaining, genuinely dramatic tv. Its biggest lesson though is best expressed by Raven:

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe