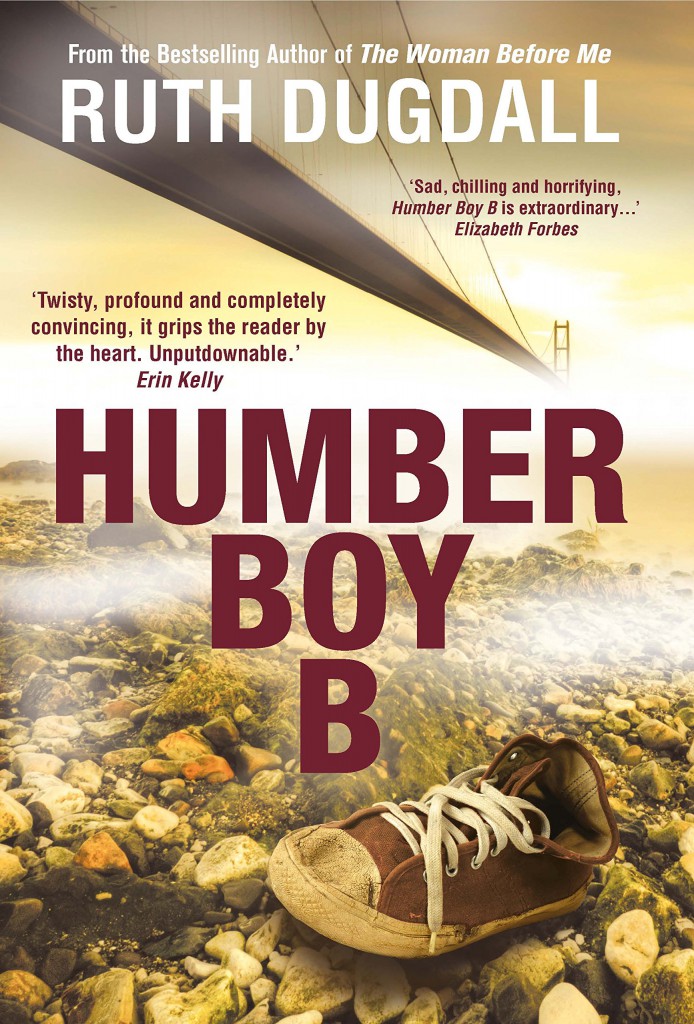

Humber Boy B is the latest novel from Ruth Dugdall, who previously won the Debut Dagger award for The Woman before Me. This is my first exposure to the author and I found this a deeply frustrating read. The book tells the story of Cate, a probation officer, and Ben, who grew up incarcerated having murdered another child at the age of ten. The plot follows Cate’s attempt to reintegrate Ben into society as figures from the past seek retribution against Ben, known only to the public as Humber Boy B.

Sadly unwilling to scratch much below the surface

The problems with the novel are stylistic as well as conceptual. The overt mission statement of the book, both from its blurb and the characters’ internalised thoughts, is to delve into the history of this fictitious child murder (which has explicit similarities to and is actively compared with the Jamie Bulger case) and try to draw out how young children can do horrific things to each other. Dugdall is sadly unwilling to scratch much below the surface.

Effort is certainly put into creating context. The flashbacks present the day of the murder in discreet sequences and we are given details of the social and economic background that Ben, his accomplice and brother Adam, and victim Noah grew up in. The murder is not treated as an isolated act of malevolence but a culmination of abuses and psychological effects impressed upon the children by the adults in their lives, which is mirrored by Cate’s family history. The sections of the novel where Cate and Ben have to confront the emotional reality of their childhoods are lent validity by the work Dugdall puts in.

This context, at least, is a strong dimension of the writing. But these strengths are not born out. Context is provided but both Ben and Adam’s rationale for their actions are not particularly lucid. The motives of child murder ought not necessarily conform to rational logic but you’ll struggle to find any meaningful analysis of violent behaviour, logical or otherwise, here. The tone of the ending suggests some satisfaction in its conclusions but there is no significant insight beyond ‘they had a hard upbringing’ which, as Cate comments earlier, is neither specific to them nor legitimate explanation for their actions.

Steeped in a tabloid mentality

A lack of firm conclusions is not always a weakness. The mature approach may indeed end up concluding that events and actions can be absurb, completely illegible to us. Humber Boy B however does not fit within in this model because it does not oscillate between interpretations of events that are either comprehensible or inscrutable. The world of Humber Boy B has two warring positions: that Ben is inherently evil and the world is separated into mawkish divisions of good and evil, or he is a product of his environment (but we are never shown how his environment really contributed to his actions in a deterministic sense). The former position is the one Dugdall seeks to dispel though she never quite gets rid of it. Other hostile forces exist in the novel that seek vengeance against Humber Boy B (as they know him) and they fit within the cartoonish malevolence that Dugdall otherwise rejects in the main characters.

Ultimately, it becomes apparent that Humber Boy B is steeped in a tabloid mentality. Certainly Dugdall should address this form of rhetoric, as Humber Boy B’s public persona and the campaigns against him are mediated through the red tops but this is the default stance of the novel. The foundation that the narrative works against is the ridiculous caricature of child murderers cast by tabloids, the hypocritical morality campaigns and preposterous hokum that make up so much of their column space. It rings as a bit too convenient that Ben, Adam and Noah go to see a gory 18-rated film on the day of the murder. As with many features of the book, Dugdall flip flops on the interpretation: it sort of affected them… maybe… This is followed by an utterly baffling Ouija board sequence in which the murder is predicted by the children. The prevalence of reductive and ridiculous assumptions on the nature of violence in children is at odds with the notion that Dugdall or her avatar Cate can meaningfully dissect these events or their participants.

Tired and predictable tropes of a crime thriller

The novel is not without its structural charms though. The book cycles through different threads of perspective and time. We are shown the parallel viewpoints of Cate and Ben, social media postings from campaigns about the newly released Humber Boy B, and events of the day of the murder. The layout is managed well – neat in both its pacing and ordering its sequences for thematic comparison and correspondence. I just wish this care had been taken on other matters of style.

The novel is not without its structural charms though. The book cycles through different threads of perspective and time. We are shown the parallel viewpoints of Cate and Ben, social media postings from campaigns about the newly released Humber Boy B, and events of the day of the murder. The layout is managed well – neat in both its pacing and ordering its sequences for thematic comparison and correspondence. I just wish this care had been taken on other matters of style.

There are many features that break the veneer of the fictional world or undermine its intents. The behaviour and diction of the child characters is wildly inconsistent. At times it rings very true, at others you cannot sincerely believe the lines are coming from a ten- or fourteen-year-old. Narrative voice is something that is generally struggled with. Cate represents the most stable and believable perspective in the book, but Ben’s adult persona seems very disingenuous. We are told repeatedly that he has educated himself and become well-read in prison but his literariness seems to be of no more purpose than to expunge the difficulties of putting a Hull accent on the page or having reflective passages from a character with limited means of expression. Only the children in the flashback sequences, whose voices are not offered up indirectly through the discourse, are afforded the leeway to remain regional.

Then there is the unease with which the attempts at introspection sit with the trashier elements of the plot. Whether or not Dugdall manages to achieve understanding oft he motives of murder, this is a weighty issue. Yet this reflection is at times grafted onto the tired and predictable tropes of a crime thriller. The book works best when Ben and Cate are working at getting their lives on track. When Facebook vigilantes and manipulative figures from the past start rearing their heads to try and hunt Ben down, the thematic introspection is derailed and tone clashes swerve violently into pulp. The assumption seems to be that the reader cannot be expected to invest in the central premise of the novel so must be placated with weak and clichéd action, with baddies, femme fatales and crass confrontations. This is perhaps Humber Boy B’s biggest sin.

No, that’s a lie. The worst bit is Cate’s vapid romance with an aloof European police officer. Just dreadful.

Verdict: Humber Boy B is well structured and has a good grasp of emotional trauma, but these are sadly small elements in an otherwise underwhelming and at times outright irritating read.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe