Literary ascension is an objective of many genres. Science fiction and fantasy continually battle to have their literary entries recognised, more unconventional media like comic books lobby for validation of their literary qualities, and the digital era may produce new forms of writing that will have to fight for their claim on literary value. Then we have pornography.

Literary ascension is an objective of many genres. Science fiction and fantasy continually battle to have their literary entries recognised, more unconventional media like comic books lobby for validation of their literary qualities, and the digital era may produce new forms of writing that will have to fight for their claim on literary value. Then we have pornography.

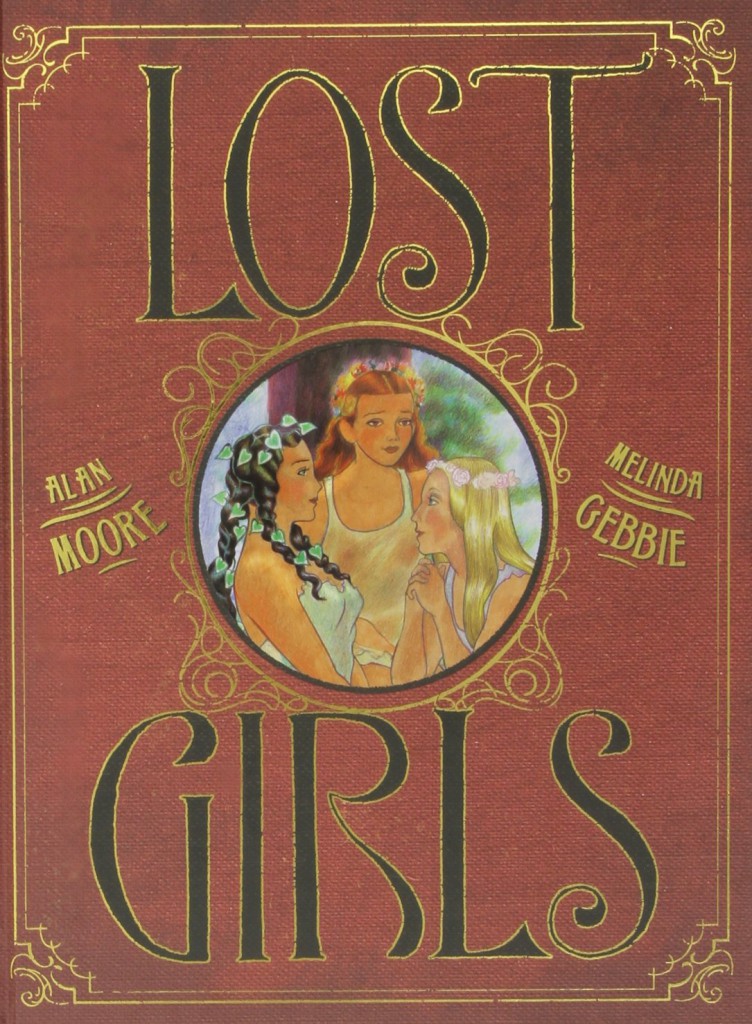

Having just finished Alan Moore’s self-declared work of pornography, the comic Lost Girls, I find myself pondering a lot of the issues surrounding the conventions of excluding purposefully sexually stimulating material from the literary canon. Of all the organs I had expected Lost Girls to stimulate, I had not anticipated it would be my brain.

It must be said from the off that Moore and artist Melinda Gebbie had a mission statement of elevating pornography. Moore said in an interview in Science Fiction Weekly in 2006:

Certainly it seemed to us that sex, as a genre, was woefully under-represented in literature. Every other field of human experience—even rarefied ones like detective, spaceman or cowboy—have got whole genres dedicated to them. Whereas the only genre in which sex can be discussed is a disreputable, seamy, under-the-counter genre with absolutely no standards.

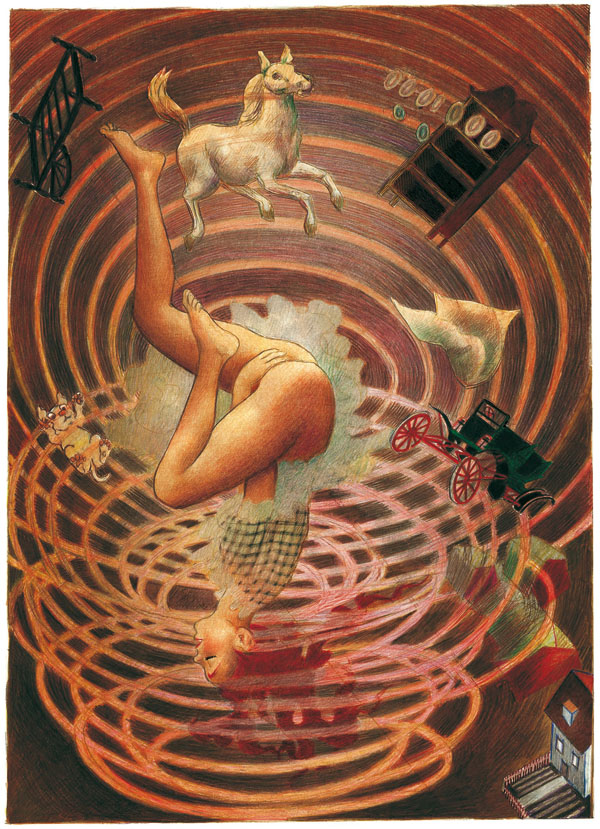

So Lost Girls functions at once as a piece of pornography but also lays out the creators’ ideology of pornography. Indeed, the literary conventions employed are used in a self-reflexive manner, largely reconstructing other literary works in a sexual context (specifically Peter Pan, The Wizard of Oz and Alice in Wonderland). Porn is discussed at length in the speech-bubbles overlaying an orgy and the ‘trangressive’ subject matter is deployed in such a way as to interrogate its inclusion and the ethics surrounding such subject matter.

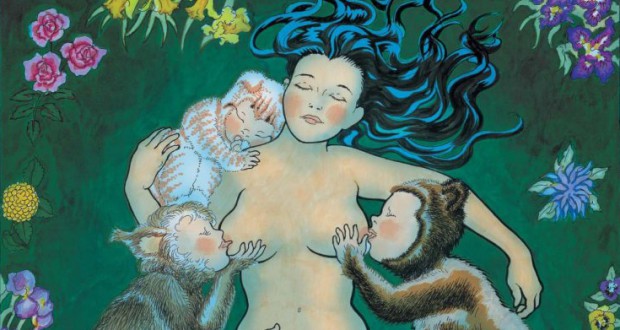

To draw out the last point, Moore and Gebbie depict prostitution, rape, abuse, incest and paedophilia. The only thing they are slightly more coy about is bestiality which is only employed in a fantastical context or left reported but not fully depicted (a horse’s cock penetrates one panel but we do not see the character perform the acts she describes upon it).

To draw out the last point, Moore and Gebbie depict prostitution, rape, abuse, incest and paedophilia. The only thing they are slightly more coy about is bestiality which is only employed in a fantastical context or left reported but not fully depicted (a horse’s cock penetrates one panel but we do not see the character perform the acts she describes upon it).

Some of the areas are hardly new for the cavalcade of material released by the professional porn industry, though to say that ‘the “disreputable, seamy” purveyors of porn produce scenes acting out rape or incestuous intercourse and that makes it okay’ is not a robust moral benchmark. And scenes depicting underage characters remain illegal. How then are we to regard these elements in the context of Moore and Gebbie’s mission statement?

One character, in the aforementioned orgy scene, expounds on the justification of sexual fantasy in that by being predicated on pretence, it is essentially harmless. The children are precisely as old as the ink on the page and the same can be said for the adults so distinctions are arbitrary. This does align with certain schools of sexual analysis that identify abnormal fantasies not as desires to be acted out, but play-constructs that derive their power and pleasure from transgressing taboos.

One character, in the aforementioned orgy scene, expounds on the justification of sexual fantasy in that by being predicated on pretence, it is essentially harmless. The children are precisely as old as the ink on the page and the same can be said for the adults so distinctions are arbitrary. This does align with certain schools of sexual analysis that identify abnormal fantasies not as desires to be acted out, but play-constructs that derive their power and pleasure from transgressing taboos.

On the other hand, the fantasist character (himself fictional) in turn admits to a history of sodomising young boys. So the point drummed out in the sex party, that his debauched fantasies remain ethically robust by their existence as fantasy, is undermined by his history. But his history too is of course fictional. This is the web of metafictional strands that Moore and Gebbie use to illustrate the complexities of sexual morals in fiction.

The fact that the comic is even raising points of sexual morality rather than circumnavigating them in its no-holds-barred flurry of tribadism, cunnilingus, fellatio, rimming, frottage, 69ing, daisy chaining, spit roasting, footjobs, and arse play is an achievement. But does that equate to literary standards?

Moral sophistication and elucidation is one route to be taken to investing a book with artistic quality but Moore and Gebbie appear to qualify the artistic merits of Lost Girls in a number of directions.

Moral sophistication and elucidation is one route to be taken to investing a book with artistic quality but Moore and Gebbie appear to qualify the artistic merits of Lost Girls in a number of directions.

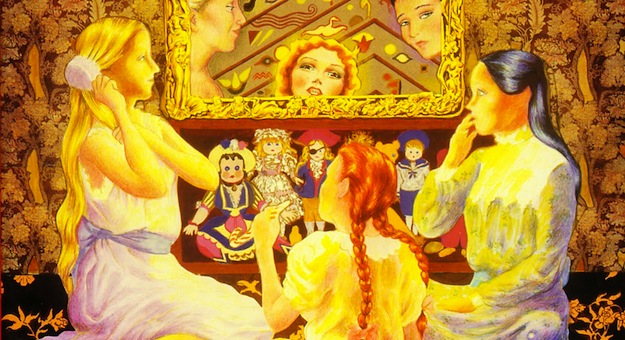

Firstly, the book reinterprets works of fiction as fantastical constructs through which the female characters have tried to understand their sexual identities in a period (the book takes place in 1913 and depicts events going back into the Victorian era) that placed serious restrictions of female expression and conduct. In turn, the main characters are from different social strata and age groups, facilitating the analysis of sexual convention across the class system and each woman confronting their sexual revelations at very different points in their life.

The historical setting is perhaps the most poignant aspect. Lost Girls contrasts the sexual liberation and revivification of its central triumvirate to the mass deaths of young men in World War I. Links between orgasms and death, the old ‘la petite mort’, are drawn out across culture but this is the first time I have seen an outdoor lesbian sex scene overlaying the assassination of Franz Ferdinand.

For the uninitiated, ‘la petite mort’ is an idiom referring to an orgasm, or more specifically the sense of transience and sadness immediately following. The book structurally reflects this with the movement from riotous sex to a melancholic vignette of Europe in the grips of war. Crucially, the literary critic Roland Barthes posited that the purpose of literature itself is to emulate this feeling. A piece of great literature is to bring you to climax and induce a sense of loss and impermanence as the sensation passes.

For the uninitiated, ‘la petite mort’ is an idiom referring to an orgasm, or more specifically the sense of transience and sadness immediately following. The book structurally reflects this with the movement from riotous sex to a melancholic vignette of Europe in the grips of war. Crucially, the literary critic Roland Barthes posited that the purpose of literature itself is to emulate this feeling. A piece of great literature is to bring you to climax and induce a sense of loss and impermanence as the sensation passes.

I am not sure I am yet ready to venture a firm conclusion on Lost Girls existence as literature but I am yet to find another piece of pornography that was even remotely as intelligent, ambitious or left me pondering so many issues.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe