Five shocking days in the life of an alcoholic

While Wilder’s 1945 Oscar winner, The Lost Weekend, was not the first big-screen look at alcoholism, it was one of the earliest to take such an honest and unrelenting approach. Though alcoholism was garnering more attention amongst the medical industry and Freudian’s psychoanalytic theories becoming more commonplace, there was still little in the way of public awareness of addiction as a disease.

The Lost Weekend has not entered the pop culture consciousness like some of Wilder’s other films, such as Some Like It Hot, The Apartment, or Sunset Boulevard, but the film has plenty to recommend itself as a classic, including an Oscar-winning performance from Ray Milland, stunning cinematography, meaty subject matter, and subtle circumnavigations of censorship.

Leave me my vicious circle

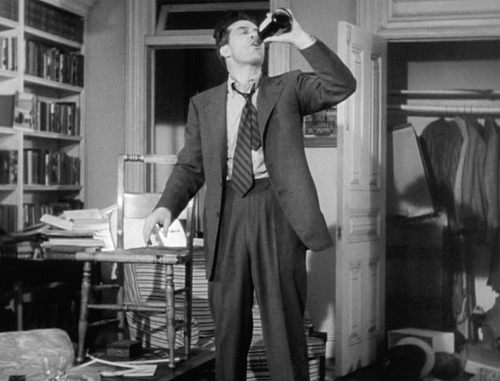

The Lost Weekend never shies away from the disturbing realities of addiction, from Birnam’s thievery to casting his loved ones as villains trying to keep him from what he needs. The story follows the diseased mind on one of the worst aspects of alcoholism: the ingenuity an addict’s desperation breeds. Birnam is a compelling protagonist because he is an unapologetically active character. From start to finish, Birnam is taking matters into his own hands, bypassing all obstacles in his way to get to the one thing he wants – another drink.

The Lost Weekend never shies away from the disturbing realities of addiction, from Birnam’s thievery to casting his loved ones as villains trying to keep him from what he needs. The story follows the diseased mind on one of the worst aspects of alcoholism: the ingenuity an addict’s desperation breeds. Birnam is a compelling protagonist because he is an unapologetically active character. From start to finish, Birnam is taking matters into his own hands, bypassing all obstacles in his way to get to the one thing he wants – another drink.

Above all else, the film is a psychological study of a disturbed mind. We are privy to the endless cycle of ‘just one more’ and how those around him, though having the best intentions, become Birnam’s enablers. The character’s descent into hell involves so many ups and downs in a limited period, the film is both exhausting to watch and representative of the realities of the illness. As a viewer, you find yourself both routing for Birnam to succeed at his latest mission of alcohol acquisition while cursing him for his destructive behaviour. We become like Birnam himself – people of two minds – writer and drunk, accomplice and critic.

Confessions of a booze addict; the log book of an alcoholic

Film noir made its name delving into the seedier parts of life, issues most filmmakers and genres tended to shy away from. As if dealing with alcoholism head-on weren’t enough, Wilder clashed with the Breen Office censors in other ways as well. At the time, it was not the ‘done thing’ to have a character as a prostitute, though this is clearly what Gloria is.

Film noir made its name delving into the seedier parts of life, issues most filmmakers and genres tended to shy away from. As if dealing with alcoholism head-on weren’t enough, Wilder clashed with the Breen Office censors in other ways as well. At the time, it was not the ‘done thing’ to have a character as a prostitute, though this is clearly what Gloria is.

The studio, Paramount, was very concerned with her depiction and the potential for the film to be banned as a result. Thus, Gloria’s profession is never specifically called out, though it is obvious to everyone what she is. She is an interesting character in other respects as well. Smitten with the charismatic Birnam, despite knowing of his fatal flaw as well as his involvement with the saintly Helen, Gloria is both a stereotypical ‘whore with a heart of gold’ while avoiding the cliché at the same time. She has layers and depth often lacking in even modern depictions of prostitute supporting characters.

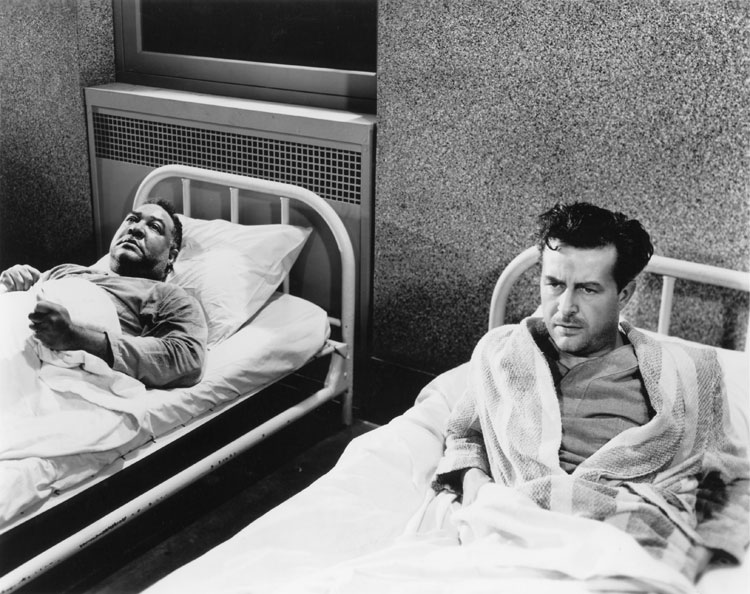

Along with prostitution, Wilder managed to sneak in what appears to be a gay nurse. Bim is a curious character, appearing only much later in the film and only ever interacting with Birnam. Some critics have wondered whether Bim and Birnam’s experience in the hospital is real or part of the delirium tremens Bim warns our protagonist will soon hit. After all, Bim is a very similar name to Birnam and is hardly the most nurturing care worker. Interestingly, in the novel the film is based on, there are supposedly (I have not read it) multiple allusions to Birnam being a repressed homosexual. Is Bim, and his apparent homosexuality, a way for Birnam to process his underlying anxieties? Is the root cause of all Birnam’s trouble repressed homosexuality? Censors missed what seems obvious to a modern viewer as a gay on-screen character, with Wilder having avoided any overt references.

Along with prostitution, Wilder managed to sneak in what appears to be a gay nurse. Bim is a curious character, appearing only much later in the film and only ever interacting with Birnam. Some critics have wondered whether Bim and Birnam’s experience in the hospital is real or part of the delirium tremens Bim warns our protagonist will soon hit. After all, Bim is a very similar name to Birnam and is hardly the most nurturing care worker. Interestingly, in the novel the film is based on, there are supposedly (I have not read it) multiple allusions to Birnam being a repressed homosexual. Is Bim, and his apparent homosexuality, a way for Birnam to process his underlying anxieties? Is the root cause of all Birnam’s trouble repressed homosexuality? Censors missed what seems obvious to a modern viewer as a gay on-screen character, with Wilder having avoided any overt references.

The production: Language, lighting, and low angles

No part of The Lost Weekend, from the acting, writing, and production, could be labeled anything but excellent. Wilder was an exceptional filmmaker with an attention to detail spanning his careful choice of language in dialogue to intriguing shots using the exquisite light to full effect. The film is moody and beautiful, with the angles, shadows, and reflections used to complement Milland’s performance of a diseased mind. We see the deterioration of Birnam’s mind in the hospital obscured by the shadows of wire holding him in his prison, for instance.

No part of The Lost Weekend, from the acting, writing, and production, could be labeled anything but excellent. Wilder was an exceptional filmmaker with an attention to detail spanning his careful choice of language in dialogue to intriguing shots using the exquisite light to full effect. The film is moody and beautiful, with the angles, shadows, and reflections used to complement Milland’s performance of a diseased mind. We see the deterioration of Birnam’s mind in the hospital obscured by the shadows of wire holding him in his prison, for instance.

The script holds up with its natural sounding dialogue. Birnam calls out Gloria for her ‘loathsome abbreviations’, as she uses ‘natch’ and ‘ridic’, words that that have since made it into common parlance. The phrase ‘thanks but no thanks’, Gloria’s casual dismissal of an unattractive potential customer, is another instance of beautifully crafter dialogue that has also made it into everyday use. These small details are not limited to the script. A lovely character tick of Birnam’s, always initially taking his cigarette backwards, something that would undoubtedly be unbearably heavy-handed in a modern film, is done smoothly and subtly throughout.

Though difficult to watch at times for its frank portrayal of alcoholism, The Lost Weekend is deserving of its title as a masterpiece.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

One comment

Pingback: #71 The Lost Weekend – 1000 Films Blog