Last week we looked over the dense, messy and admittedly somewhat disputed publication history of Miracleman. Whilst the trajectory of the comic and character has dovetailed with some of the major events of the industry (usually waves of bankruptcy), the influence of the character as he existed in the pages is what really left its mark on the medium.

The 1990s saw an explosion of dark anti-heroes in comics. The traditional narrative is that with the popularity and acclaim of Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns in 1986, the market seized on the nominally more mature content that comics were now allowed to field, and waves of gore and flawed gruff heroes emerged. Of course, this is a gross simplification. The truth is that flawed, complex and morally grey characters had existed before. The ‘overdue’ dark revamp of Batman had begun before with the work of Steve Englehart. The era that followed was coached more in arbitrary gratuity and needlessly antagonistic characters than moral complexity.

The 1990s saw an explosion of dark anti-heroes in comics. The traditional narrative is that with the popularity and acclaim of Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns in 1986, the market seized on the nominally more mature content that comics were now allowed to field, and waves of gore and flawed gruff heroes emerged. Of course, this is a gross simplification. The truth is that flawed, complex and morally grey characters had existed before. The ‘overdue’ dark revamp of Batman had begun before with the work of Steve Englehart. The era that followed was coached more in arbitrary gratuity and needlessly antagonistic characters than moral complexity.

But this was also the era of where the deconstruction of the superhero genre was printing alongside the worst excesses of the early Image and Wildstorm comics. We had Warren Ellis’ Stormwatch and The Authority, Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol and The Invisibles. But where did the DNA of these comics that delved into the twisted ideologies of the superhero come from? Many would vouch for Watchmen. But no, it is Miracleman.

But this was also the era of where the deconstruction of the superhero genre was printing alongside the worst excesses of the early Image and Wildstorm comics. We had Warren Ellis’ Stormwatch and The Authority, Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol and The Invisibles. But where did the DNA of these comics that delved into the twisted ideologies of the superhero come from? Many would vouch for Watchmen. But no, it is Miracleman.

I am rarely one to get behind authorial intent. However, I have to agree with Moore when he asserts that the point of Watchmen was to produce something that could only be done in comics (we could dedicate an article to the formalism of THAT comic), and his work designed to dissect the identity of the superhero is the premier British cape, Miracleman. Continuity of theme does exist between the two but it is the latter which stamped Moore’s central hypothesis first: the superhero is a source of terror, not awe.

The deconstruction of the superhero stems from teasing out their relationship to power

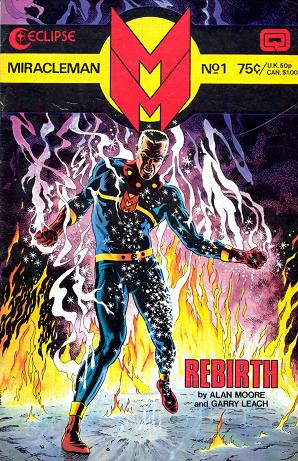

It’s the 80s. Micky Moran is a middle-aged journalist. He has a childless marriage with Liz. He gets headaches. He dreams of flying. Whilst visiting a nuclear power station surrounded by protesters, terrorists take the press group hostage. Near passing out as stress and migraines besiege him, Micky suddenly says a word that has been on the tip of his tongue for ages… KIMOTA! Thus emerges his long forgotten alter ego, Miracleman, who fights off the terrorists and saves the day. Morphing back, Micky has a world of questions. Where did that word come from? How can he manifest these powers? Was that really him, gliding, smashing and swooping about with invulnerability?

It’s the 80s. Micky Moran is a middle-aged journalist. He has a childless marriage with Liz. He gets headaches. He dreams of flying. Whilst visiting a nuclear power station surrounded by protesters, terrorists take the press group hostage. Near passing out as stress and migraines besiege him, Micky suddenly says a word that has been on the tip of his tongue for ages… KIMOTA! Thus emerges his long forgotten alter ego, Miracleman, who fights off the terrorists and saves the day. Morphing back, Micky has a world of questions. Where did that word come from? How can he manifest these powers? Was that really him, gliding, smashing and swooping about with invulnerability?

And with that first brazen outing of the Moore run, we have the basic premise of secret identity twisting about. Micky’s response to this limitless empowerment is not that of the archetypal hero (or villain). His mind does not abound with what these powers will allow him to do, what possibilities are open to him, what he can get away with. No, there is uncertainty, confusion and fear. Faced with the prospect that his physical and mental prowess expands beyond reason when he transforms, his sense of identity dwindles. How can he be the same person when he becomes someone explicitly taller, smarter and more powerful?

The deconstruction of the superhero stems from teasing out their relationship to power, rather than the adherence to what in most comics tends to be a rather flimsy morality. For whilst Micky/Miracleman decides to use his power for good, it is the response to that power which shapes his existence. Perhaps the most tragic figure in this ripple effect is his wife Liz, who is initially faced with having a new infinitely more capable lover. For Liz, this revelation sees her move from being scared, to being enthralled, and ultimately being left behind by an entity she can no longer seek to understand. Micky’s primary human connection is lost over time as he acclimatises to being something beyond human.

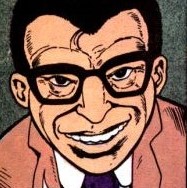

Having destroyed the idealised fun of the secret identity and the love interest with the morose degradation of Micky and Liz’s domestic life, Moore turned to his villains to next overturn the unquestioning tropes of classic comics and infantile wacky hijinks unwilling to tackle the implications of their content. The cruel progenitor of the project from which Miracleman is spawned, Dr Gargunza, is a pulp villain taken to its natural conclusion. Based on the Captain Marvel baddie Dr Sivana, Moore’s idea was that the evil genius would not simply be interested in wacky superweapons but be part of a lineage of scientists using their craft to degrade and defile human rights. A former Nazi scientist, rapist and sociopath, Gargunza grasps at power because he believes by mastering alien technologies, he can rest control over his own mortality. Every action he takes is explicitly about gaining power over another being in order to enslave or abuse them.

Having destroyed the idealised fun of the secret identity and the love interest with the morose degradation of Micky and Liz’s domestic life, Moore turned to his villains to next overturn the unquestioning tropes of classic comics and infantile wacky hijinks unwilling to tackle the implications of their content. The cruel progenitor of the project from which Miracleman is spawned, Dr Gargunza, is a pulp villain taken to its natural conclusion. Based on the Captain Marvel baddie Dr Sivana, Moore’s idea was that the evil genius would not simply be interested in wacky superweapons but be part of a lineage of scientists using their craft to degrade and defile human rights. A former Nazi scientist, rapist and sociopath, Gargunza grasps at power because he believes by mastering alien technologies, he can rest control over his own mortality. Every action he takes is explicitly about gaining power over another being in order to enslave or abuse them.

Moore had no interest in showing a brave new world in Miracleman

It is with Gargunza that we sadly see the origins of regrettable later trends from poorer copycats. The decades that follow would see comics adopt increasingly sensationalist and tasteless spins on villainy by making similar moves but without the self-awareness and insight that Moore was bringing to the table. Gargunza’s vileness is given a context and rationale (of a revolting sort) lacking in the bizarrely incongruous backgrounds in paedophilia and sexual violence that would pervade even DC and Marvel in the coming years. Honest to god, they made Toyman a child abuser in the Superman comics!

It is, troublingly, Gargunza who shares the most common ground with the position Moore is trying to advocate as the legitimate response to a superhero phenomenon. Having created the ‘second bodies’ for a series of human subjects in experiments, Gargunza keeps his new superhuman weapons locked in mental simulations. Permanently asleep, Miracleman and his companions experienced their original child-friendly adventures as engineered simulations. In an arc known as The Red King Syndrome, Gargunza extemporises that much like the character from Alice through the Looking Glass, everyone feared that Miracleman would wake up in case all that existed was simply a dream of his. The world as we know it cannot sustain contact with such a being and remain unchanged. And Gargunza is right: with the rise of the superheroes, change comes, and it is painful.

It is, troublingly, Gargunza who shares the most common ground with the position Moore is trying to advocate as the legitimate response to a superhero phenomenon. Having created the ‘second bodies’ for a series of human subjects in experiments, Gargunza keeps his new superhuman weapons locked in mental simulations. Permanently asleep, Miracleman and his companions experienced their original child-friendly adventures as engineered simulations. In an arc known as The Red King Syndrome, Gargunza extemporises that much like the character from Alice through the Looking Glass, everyone feared that Miracleman would wake up in case all that existed was simply a dream of his. The world as we know it cannot sustain contact with such a being and remain unchanged. And Gargunza is right: with the rise of the superheroes, change comes, and it is painful.

Moore had no interest in showing a brave new world in Miracleman. Though perhaps now the idea that there is fallout from the demolition derbies that superhero fights become is more commonly held, at the time the destruction of cities in nigh apocalyptic scale was new. No one stands about cheering how the earth is saved. There is rubble, fire and death when Miracleman has to throw down with opponents of his own power level. And not in the way that Marvel/DC comics lampshade the event but things carry on more or less the same sort of way. The violence, as in real life, is an agent and by-product of great change.

So often, the Nietzschean philosophy of the ubermensch is transposed in its crudest form

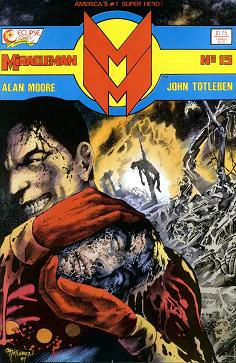

It is worth perhaps reflecting on the use of graphic content given that this, more than anything, would be the heritage that Miracleman left behind it. Compared to Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns, the generic codifiers for the craze to come, Miracleman is substantially gorier and dedicates a lot more time to the weird logistics of superhuman sex. But I draw attention to this to contrast the origins with the results. Whilst now we have comics where grotesque mutilations and bloody deaths have become the standard contrived way to manufacture drama and impact to the point of being ineffective, the diversity of the gore in Miracleman is intriguing. By far the most controversial segment is not the annihilation of London, but the birth of Miracleman and Liz’s child, Winter. Based on surgical images, Moore and the art team are using graphic anatomical details in a way that most comics still shy away from. As with so many things, most of the industry took away the wrong lessons and simply followed on showing what a psychotic superhuman would do to beings he can simply pull apart. Moore’s vital touch was to make all the sorrow and pain Miracleman’s fault. The great evil that he must face down is his insane protégé Kid Miracleman – who can only access the powers he uses to kill millions by uttering the protagonist’s name. No Miracleman, no massacre.

It is worth perhaps reflecting on the use of graphic content given that this, more than anything, would be the heritage that Miracleman left behind it. Compared to Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns, the generic codifiers for the craze to come, Miracleman is substantially gorier and dedicates a lot more time to the weird logistics of superhuman sex. But I draw attention to this to contrast the origins with the results. Whilst now we have comics where grotesque mutilations and bloody deaths have become the standard contrived way to manufacture drama and impact to the point of being ineffective, the diversity of the gore in Miracleman is intriguing. By far the most controversial segment is not the annihilation of London, but the birth of Miracleman and Liz’s child, Winter. Based on surgical images, Moore and the art team are using graphic anatomical details in a way that most comics still shy away from. As with so many things, most of the industry took away the wrong lessons and simply followed on showing what a psychotic superhuman would do to beings he can simply pull apart. Moore’s vital touch was to make all the sorrow and pain Miracleman’s fault. The great evil that he must face down is his insane protégé Kid Miracleman – who can only access the powers he uses to kill millions by uttering the protagonist’s name. No Miracleman, no massacre.

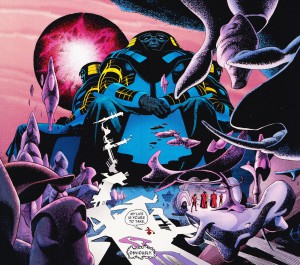

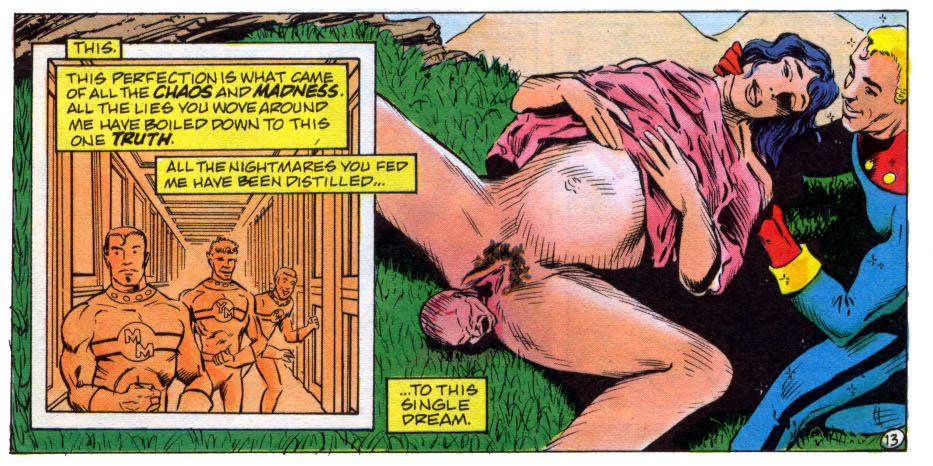

And then there is the sex. As the pantheon of Miracleman grew, the possibility for liaisons between different bizarre beings presented itself. The teleporting Warpsmiths conduct spatial orgies as they move and contort to form a swirling maelstrom of sensuous matter. Miracleman himself is taken aback by the hypnotic androgyny of Miraclewoman when she arrives. Winter, by far the most complicated figure in the work, the super-sentient infant child of Miracleman and Liz goes out into space herself to experience, in every sense of the word, all that the universe has to offer. Sex is the platform on which the boundlessness of the superhumans is made most clear as Micky/Miracleman, the most grounded of the beings having lived as a human the longest, constantly struggles to leave behind the tired human mores that can no longer apply to him.

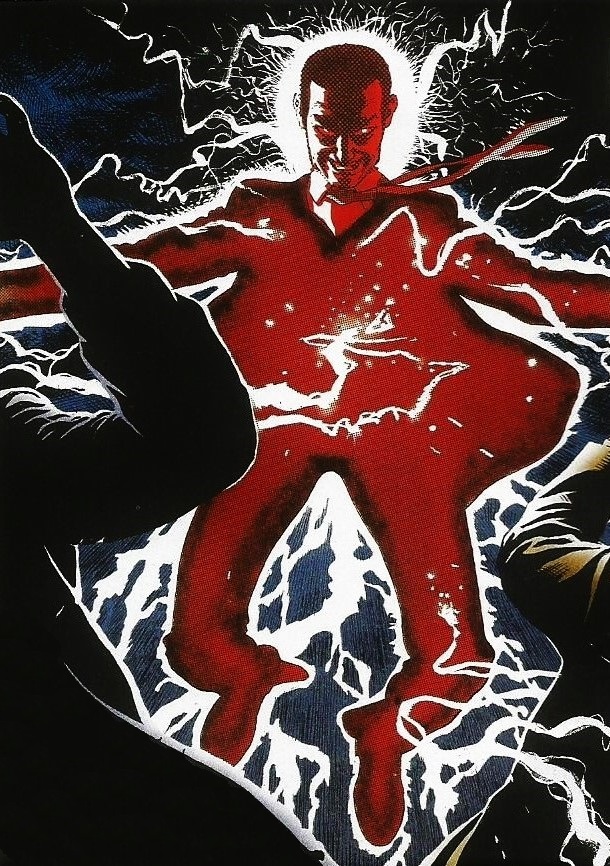

So often, the Nietzschean philosophy of the ubermensch is transposed in its crudest form. A superhuman is harder to restrain. At the point which they can no longer be forced to adhere to humanity’s conventions and laws, they will transcend and transgress them. Cue killing spree. This does indeed happen in Miracleman but is supplemented all the time by the expansion of possibilities on all fronts. The delinquent Kid Miracleman ceases to view the people around him as anything but toys to pull apart (which is the standard arc of so many archetypal supervillains in comics), but the boundaries are transgressed so far that it extends to societal change. And these are the last two strands of Moore’s hypothesis that Neil Gaiman would carry through: totalitarianism and the loss of humanity.

So often, the Nietzschean philosophy of the ubermensch is transposed in its crudest form. A superhuman is harder to restrain. At the point which they can no longer be forced to adhere to humanity’s conventions and laws, they will transcend and transgress them. Cue killing spree. This does indeed happen in Miracleman but is supplemented all the time by the expansion of possibilities on all fronts. The delinquent Kid Miracleman ceases to view the people around him as anything but toys to pull apart (which is the standard arc of so many archetypal supervillains in comics), but the boundaries are transgressed so far that it extends to societal change. And these are the last two strands of Moore’s hypothesis that Neil Gaiman would carry through: totalitarianism and the loss of humanity.

And by the end, Micky Moran has ceased to be, there is only Miracleman

Totalitarianism is not hard to tease out. Faced with the realisation that his new society of super beings is objectively stronger, faster, smarter and wiser than the meagre humans, Miracleman enacts utopia. He cannot be coerced or negotiated with from a level or equal position by the forces of man, so to resist him becomes futile. His rule is absolute. And by the end, Micky Moran has ceased to be, there is only Miracleman. Rather than defending and espousing the moral rectitude he thought he embodied, Miracleman comes to hold little common ground with the human race, living in loftier airs as an all but god. He has a wife he can no longer empathise with, a star child who cavorts through the star ways, and no power on earth to restrain him. He has ceased to be the tired man with the headaches. He has ceased to be a mere man by any definition at all.

Totalitarianism is not hard to tease out. Faced with the realisation that his new society of super beings is objectively stronger, faster, smarter and wiser than the meagre humans, Miracleman enacts utopia. He cannot be coerced or negotiated with from a level or equal position by the forces of man, so to resist him becomes futile. His rule is absolute. And by the end, Micky Moran has ceased to be, there is only Miracleman. Rather than defending and espousing the moral rectitude he thought he embodied, Miracleman comes to hold little common ground with the human race, living in loftier airs as an all but god. He has a wife he can no longer empathise with, a star child who cavorts through the star ways, and no power on earth to restrain him. He has ceased to be the tired man with the headaches. He has ceased to be a mere man by any definition at all.

And you can see how this fed certain trends in comics. There was a desire to emulate the take on the superhero that included mad scientists, secret identities, ever burgeoning casts of fantastic characters that also allowed for more explicit themes and mature takes on loss, corruption, politics and power. Some were successful. Some were not. Many were oblivious as to where this trend started.

Where others found wonder and awe, Moore found dread and apprehension. There are indeed many great inheritors to this story but I challenge you to find a comic so unswervingly intelligent and ambivalent about the obsession of our pop cultural era: the man in silly tights.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe