Sometimes great stories happen behind stories too. In an era where superhero comics dominate so much of other media, it is interesting to look at the more obscure tales that have nonetheless had a profound impact on the medium, industry, and with their greater cultural profusion, our culture at large. It can also be valuable to see how they emerged.

Miracleman is one such comic. It will not be made into a movie anytime soon. It will never be marketed with the all-ages fervour of The Avengers or the puerile adult appeal of Deadpool. It is the key foundation of the dark revision of superhero comics (for better or worse). Before The Dark Knight Returns, before even Watchmen, there was Marvelman. What’s that? I just got the name wrong? Oh, ho ho ho. Let us not even delve into the weird content of the comic. That we can save for another day. Let me instead reveal how labyrinthine the hinterland of this comic is.

1940 saw the first appearance of Captain Marvel in a publication of Fawcett Comics. The big red muscle man bore a striking resemblance to a certain big blue boy scout owned by DC Comics, but the pretender was outselling his peer substantially in the 1940s. How did DC conquer this do-gooder? They sued. In 1953, DC successfully won a copyright infringement case against Fawcett who then ceased publication. Until DC would buy a license for the character from Fawcett in the 70s, Captain Marvel did not appear in this incarnation for decades. And in the interim, an upstart comic book outfit from New York called Marvel would eventually produce their own Captain Marvel character. But we are not telling their stories. As with so much of this messy tale, something new was birthed from the chrysalis of copyright infringement and legal wrangling.

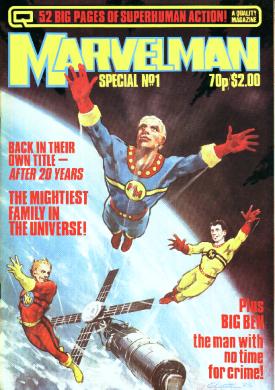

America had not been the only place that Captain Marvel had taken off in. A company called L. Miller & Son, Ltd had been making some tidy sums by obtaining the license for Captain Marvel’s black and white reprints in the UK. But then misfortune struck when Fawcett ceased publication of the big red lug. Len Miller was not deterred. Hiring a man named Mick Anglo for writing duties, Miller unofficially continued the comic. Using logos resembling but subtly distinct from Fawcett’s, 1953 saw the birth of Marvelman.

Suddenly on the other side of the Atlantic, this new figure emerges

Billy Batson was a boy reporter who, empowered by a wizard, could speak the magic word ‘SHAZAM!’ and become the World’s Mightiest Mortal – Captain Marvel. He was joined by friends who would come to share his power, the wholesome Marvel Family of Mary Marvel, Captain Marvel Jr. and Uncle Marvel. There were more obscure members but the less said about Lt. ‘Hillbilly’ Marvel and Lt. ‘Fat’ Marvel, the better. Suddenly on the other side of the Atlantic, this new figure emerges. A kid journalist called Micky Moran is empowered by an astrophysicist, so that upon saying the word ‘Kitoma!’ (wait for it) he can access terrific atomic energy powers to become Marvelman. Later joined by his trusty sidekicks Young Marvelman and Kid Marvelman, this trio of do-gooders were purpose built to have the superpower of readership retention.

In 1954, the new versions of the Marvel family launched in Britain and for 6 years, Mick Anglo wrote what are held by its fans to be fun, inventive and wacky stories of daring-do. Some were rehashes of old Captain Marvel material, but there was plenty new and Anglo was prolific. There are well over 700 issues of Marvelman and Young Marvelman in this period, in addition to the Marvelman Family comic and a series of annuals. And they sold well both domestically and abroad. Never being shipped to America, for obvious reasons, Marvelman did make his way to Italy and Brazil. Then the Americans did the unthinkable, they used a change in British legislation to export more and more of their superhero comics to the UK. The monsters!

Faced with the sheer quantity of new material in colour, rather than black and white print, the home-grown audience for Marvelman dwindled. And Mick Anglo’s time with his spuriously created character was coming to an end. Working in an era of imperious studio control and disrespect, Anglo left Miller’s publisher in 1960. Len Miller would churn out reprints for a few more years but shut up shop in 1963. Anglo pioneered the next metamorphosis of this form-shifting hero when he founded Anglo Comics in 1960 and produced a comic about a familiar figure now called Captain Miracle. But the market was gone and he ceased publication in 1961.

And now the archnemesis of the piece shall rear its head again: copyright. It was in that brief run of Captain Miracle that Mick Anglo had published copyright lines in the margins. From a property that had its roots in the flagrant plagiarism and cynical commercial opportunism of the 1930s comics industry (as if that EVER stopped), now the shape-shifting beast would follow the industry conflict which would rage for much of the second half of the century: creators’ rights. Near two decades passed before Marvelman (or Captain Miracle) appeared again.

Litigious Americans sallied forth once more

In 1982, an anthology comic rival to countercultural punky sci-fi touchstone 2000AD was launched; the brainchild of Dez Skinn, the comic was called Warrior. After several failed solicitations, Skinn managed to find some down-on-his-luck schmuck to revive the beloved Marvelman comics of his youth for Warrior. The name of this young writer? Alan Moore. With a dense and deconstructive style that would later underpin all his work, Moore came at Marvelman from a new angle. 20 years had passed since we had seen the hero, and the first comic opened with a middle-aged Micky Moran complaining about his migraines and his dreams of flying. As the new series took off with its take on the character along with reprints of the Mick Anglo material, litigious Americans sallied forth once more.

Marvel Comics had now emerged from a rebranding of Atlas Comics and threatened proceedings if Warrior continued to use the word ‘marvel’ in one of its ongoing series. The story was put on hiatus, though the anthology kept running briefly. Dez Skinn became renowned for his mistreatment of creative staff and Alan Moore refused to churn out more work during an ongoing fracas between himself and Skinn. With other (unpaid) staff departing and Warrior increasingly uncompetitive, it shut down and Marvelman had ended on a cliff-hanger. But as so often happened with the character, Marvelman had found outlets elsewhere. Whilst battling with Moore, Skinn had licensed a reprint of the Marvelman material to American publisher Eclipse Comics. Eclipse was cannier than to start picking fights with Marvel though so gave the comic a new name: Miracleman.

It was now 1985 and with only a small backlog of Alan Moore stories, Eclipse needed more of this subversive and surprisingly profitable material even though Warrior was gone. Where to get new stories? They simply hired Alan Moore (he was out of work after all) and artist Chuck Beckum to replace Alan Davis on the book. Beckum did not last long and Moore was joined by Rick Veitch and John Totleben (his later collaborators on Swamp Thing). Here Eclipse added to the mess of rights issues surrounding the now-rebranded Miracleman. They signed with Moore and the artists such that Eclipse held 2/3 of the rights to the property, the creative team held 1/3. Moore concluded his story for the character with issue 16 and then some writer who never amounted to anything took over: Neil Gaiman.

The intrepid hero was left on an indefinite cliff-hanger

Gaiman’s after-The-Event version of Miracleman spun out on the slow and steady publication schedule until 1994, in which time he inherited the rights that Alan Moore had shared with Eclipse. At that point, Eclipse went bankrupt Miracleman halted once more at issue 24. All the material Gaiman and his collaborators had prepared for the succession of his ‘Golden Age’ arc went unpublished and yet again because of the folly of the publisher, the intrepid hero was left on an indefinite cliff-hanger. Time passed and a new figure walked into the arena: Todd McFarlane.

McFarlane, darling of the 90s gritty superhero phase and creator of Spawn, bought out Eclipse’s creative assets. By 2001, he had started inducting their characters, including Mike Moran, into his Hellspawn comic and then producing Miracleman figurines for his extensive merchandising operations. He went the whole hog by then introducing a mysterious ‘man of Miracles’ in Spawn #150 – another name change for our illustrious hero. The problem? He denied any shared rights with the previous Eclipse creatives and they saw none of the profits. Gaiman now went on the offensive.

As part of a series of lawsuits that Gaiman proceeded with against McFarlane over a number of disputes during Gaiman’s work on the Spawn title, Gaiman set up ‘Marvels and Miracles LLC’. The sole role of this entity was a herculean task: sorting out who ACTUALLY owned the rights to the Marvelman/Captain Miracle/Miracleman/Man of Miracles character.

Now, pay attention here.

In 2002, Marvels and Miracles LLC found that the McFarlane claim to the rights was illegitimate because when he had bought the rights from Eclipse, the purchase for their creative material had not included Miracleman. The buyout of Eclipse’s creative property did not include this because they didn’t own the rights. So neither did any of the creative staff they had split the rights with. They did not own the rights because they had purchased the license and subsequent rights to publish from Quality Communications (publishers of Warrior) who, in turn, had never owned the rights. Quality Communications had not owned the rights because their publication was predicated on buying them from the receiver of Len Miller’s assets. Miller’s company had never actually gone into receivership so this claim of purchase was fraudulent. Marvels and Miracles LLC found that by printing his little copyright line in the handful of issues of Captain Miracle back in 1961, original writer Mick Anglo had had the rights all along, and not this string of publishers.

New audiences were given the chance to familiarise themselves with the contentious hero

But does this story ever get a happy ending? Somewhat. Mick Anglo, mauled and mistreated by the comic industry all those years ago and uncredited for his vital reinvention of a character who would go on to win the hearts and minds of many, was approached by Marvel Comics in 2009 who bought the rights from him for a series of reprints. On top of the money from this, Alan Moore (long since disillusioned with the big American publishers) refused to have his name appearing on any of the reprints of his work and demanded all the money he was due to be given to Anglo and his family instead. In 2015, new audiences were given the chance to familiarise themselves with the contentious hero when Marvel launched the first of their new trade collections. As of March 2016, the reprints of Alan Moore’s material have completed and the first collection to feature Neil Gaiman’s work has just been released. Gaiman is also providing a finale to his unfinished arc in the series.

And there you have it. With nary a great insight into the content of the comic, you see that Marvelman or Miracleman or whatever his name is has moved in one form or other through the many and turbulent eras of comics. He’s born of the commercial exploitation of the early American industry. But in Britain, he was reborn of legal loopholes whilst coming to typify the wacky adventures of the 50s. He has been the prize fought over in the battles between tyrannical management and downtrodden writers, has been halted with the frequent financial and legal mismanagement that came to be the watchword of small to mid-level publishers, he became the centre of the malpractice and unoriginality scandals of the grim and gritty 90s, and has been relaunched yet again in the recycling-obsessed modern era of comics. It’s a history created from egos, a prolific disrespect for originality and property ownerships, unscrupulousness and frankly juvenile behaviour.

You might well wonder what sort of comic could on earth emerge from such long and sordid production cycle. Let me assure you, the results are dark and twisted indeed by their finale.

More on that next week…

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Fantastic recap of events – I’m actually reading it, and it is gradually blowing my mind (after re-reading Watchmen, V, the whole LoEG and the “final interview”, quite a feat for Miracleman, indeed);

the context of Anglo’s reprints as afternotes and echoes of sorts between the old

and new material is amazing and only multiplies the sheer value of the remarkable story.

Quite a testimony of the 80’s, a solid historical period that gave us several shards of global art on a scattered humanity pattern.

Long live the Original Writer, because without his work on Miracleman,

I’m almost certain there wouldn’t be MANY things nowadays.

As you said, for the better or the worse, Kimota. Not two doubts about it.