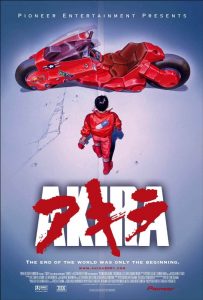

Any list of most influential and greatest anime will inevitably feature one name above all others. Some have favourites that supersede it (indeed, I myself do) but no other film can claim as singular an impact on bringing Japanese animation to the west. That film is Akira.

For the uninitiated, the dystopian sci fi epic Akira takes place in the mesmeric post-event world of Neo-Tokyo – it concerns two teenage bike-gang members who are dropped into a world of sinister government conspiracies and disturbing psychic powers. A recent cinema screening of the 2016 remaster gave me a chance to revisit this animation spectacle and I found myself almost bowled over by its quality, in a way that did not occur when I first saw it.

For the uninitiated, the dystopian sci fi epic Akira takes place in the mesmeric post-event world of Neo-Tokyo – it concerns two teenage bike-gang members who are dropped into a world of sinister government conspiracies and disturbing psychic powers. A recent cinema screening of the 2016 remaster gave me a chance to revisit this animation spectacle and I found myself almost bowled over by its quality, in a way that did not occur when I first saw it.

There’s no doubt that one reason the film improves on subsequent viewings is because, bereft of the expectation of story, it cannot possibly disappoint. I recall my initial exposure and being struck that content had clearly been cut – it was the only explanation for the major lapses in narrative logic. The leap made between Tetsuo’s insecure psychic initiation and his sudden overwhelming urge to fight the elusive Akira is given little context, and similarly, Kei’s rapidly escalating role comes across as a deus ex machina that doesn’t actual fix any plot points. Indeed, of the 2000+ pages of the manga (which was unfinished when the film was produced) a horrific amount of content never made it in. Readers of the manga will find a radically different and expanded story on the page.

A flawed masterpiece that changed the face of animation and cinema more widely

For all the issues with the heavily abridged non-plot, Akira is still the film that broke anime into the western markets. The biggest factor in this was the sheer quality of the production. The West had been without major animation landmarks for some time (Disney having been at the tail end of its creative drought at the time) and most imported anime was of low production quality. Cost-cutting was the order of the day. Then along came Katsuhiro Otomo. Approached by several financial backers and entertainment companies, manga-author Otomo was given the biggest budget of any anime production ever helmed and he negotiated for sole creative oversight – writing and directing the adaptation of his own work.

Off the back of the 1.1 billion yen provided for the film, Otomo pre-recorded the dialogue so he could animate to match the script, produced huge detailed images for the gorgeous backgrounds, and avoided the notorious choppy animation style of most Japanese works by producing more than 150,000 cells to create hyper-fluid movement. He even indulged in pioneering computer technology to plot the vectors of objects in motion and to accurately construct parallax views in his landscapes. There had been nothing on this scale of ambition in animated cinema when it was released in 1988. And that’s to say nothing of Akira not fitting with the mainstream conception of cartoons.

Off the back of the 1.1 billion yen provided for the film, Otomo pre-recorded the dialogue so he could animate to match the script, produced huge detailed images for the gorgeous backgrounds, and avoided the notorious choppy animation style of most Japanese works by producing more than 150,000 cells to create hyper-fluid movement. He even indulged in pioneering computer technology to plot the vectors of objects in motion and to accurately construct parallax views in his landscapes. There had been nothing on this scale of ambition in animated cinema when it was released in 1988. And that’s to say nothing of Akira not fitting with the mainstream conception of cartoons.

Of course now, the idea of adult animation is much more established (even if the field is niche, it has grown and grown). But for obscurer cult material like Fritz the Cat and Heavy Traffic in the 60s and 70s, the idea of animation as anything other than children’s entertainment in the late 80s was laughable. Then in bursts Akira with its disturbing gore, god-like powers and harrowing dystopia. It found great success in Japan in 1988 and was brought to America for a limited release to America by Streamline Productions. And typically for a film challenging rather limited cultural horizons, it did far more modestly.

Notoriously Steven Spielberg and George Lucas dismissed the film as unmarketable

In fact, the myth of Akira often incorrectly casts it as breaking through on its cinematic release. The status and exposure of the film was facilitated a little later due to the economics of its home video release. Dovetailing with an influx of other higher budget anime in the early 1990s, the VHS was widely and effectively distributed and saw a market saturation which the limited theatrical release could not achieve. The successful video release was so big it, in fact, led to the formation of modern anime-distribution and dubbing juggernaut Manga Entertainment (responsible for the subsequent re-releases of the film).

It would be churlish to suggest that the film’s success is entirely predicated on the logistics of its release. Even today, on the big screen, Akira’s animation, art, and sound design are astounding. I defy anyone not to be awed by the studio-bankrupting backgrounds and the immaculately realised animation, all the while the dissonant and booming chants of the soundtrack drive you into a frenzy. Whether it is bike chases or beings of molten flesh, the skill employed in putting the ink in motion is something we still rarely see.

It would be churlish to suggest that the film’s success is entirely predicated on the logistics of its release. Even today, on the big screen, Akira’s animation, art, and sound design are astounding. I defy anyone not to be awed by the studio-bankrupting backgrounds and the immaculately realised animation, all the while the dissonant and booming chants of the soundtrack drive you into a frenzy. Whether it is bike chases or beings of molten flesh, the skill employed in putting the ink in motion is something we still rarely see.

Though approximate contemporaries like Laputa: Castle in the Sky and Ghost in the Shell may be able to supersede it in terms of narrative or theme (respectively), arguably none even to this day can challenge Akira in terms of unfettered spectacle.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe