‘And if California slides into the ocean

Like the mystics and statistics say it will

I predict this motel will be standing

Until I’ve paid my bill’

– ‘Desperados Under The Eaves’ (1976)

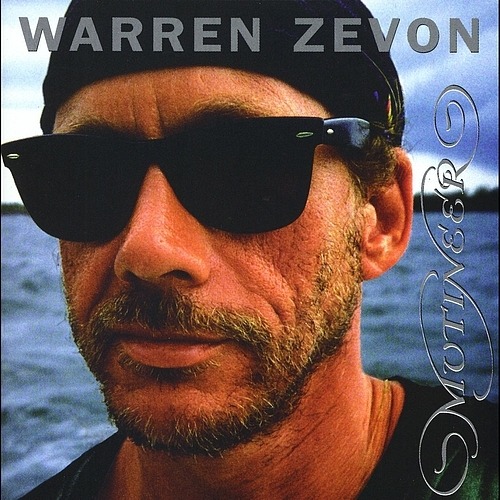

At the time of his death, ten years ago today, Warren Zevon’s songs were being performed by Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen. He could count Stephen King among his fans. He had recorded with Emmylou Harris and Jackson Browne, Billy Bob Thornton and David Letterman; written songs with Hunter S. Thompson and preeminent postmodern poet Paul Muldoon. So why haven’t you heard of him?

At the turn of the 1970s, a leafy LA suburb called Laurel Canyon had become the centre for a scene of singer-songwriters. Acts like Joni Mitchell, The Eagles, Jackson Browne and Fleetwood Mac combined breezy melody with earnest introspection to sell shit-tonnes of vinyl. Not to say this scene was without mavericks (I mean Zappa lived there!) or that these artists and their associates were lacking in a dark side or excess – just ask James Taylor’s psyche or David Crosby’s liver – but Warren Zevon stood apart. The hellraising son of an LA gangster, Zevon composed serialist music in his youth and would visit the home of Igor Stravinsky. He may have sounded superficially similar to his ‘70s songwriter peers – not least on his Jackson Browne-produced, eponymous proper debut, featuring the masterpiece our opening lines are drawn from – but none of the Laurel Canyon scene could have written ‘Excitable Boy’. Musically pleasantly inoffensive, ‘Excitable Boy’ is lyrically a pre-American Psycho tale of rape, murder and graverobbing. Perhaps only Neil Young’s David Crosby-featuring ‘Revolution Blues’ of a couple of years earlier – channelling the psychic aftermath of the murder in Laurel Canyon, by Charles Manson’s ‘family’, of Roman Polanski’s wife Sharon Tate – is as unsettlingly sinister, but not as grotesquely funny.

When it comes to quality and consistency, I’d rather have three transcendentally great tracks on an album of filler than an hour of consistent mediocrity – and Zevon certainly fell into the former camp. His one hit single was ‘Werewolves of London’, ably performed here by Adam Sandler. He was on occasion capable of consistency (1978’s Excitable Boy, his 2000 masterpiece Life’ll Kill Ya) but I sometimes find myself in the position with great songwriters – Leonard Cohen and Nas among them – of revering the songwriting while wanting to ask, really? That’s the backing you’re going with? The eighties were a decade of badly dated synth tones and studio tinkering for Zevon. The best place to start is his 1993 live album, Learning to Flinch. Reduced by a decade of inconsistency and hard drinking to touring solo, Flinch allows him to simultaneously strip back his greatest compositions while displaying his virtuosity on both piano and guitar. After a raft of highlights, it’s crowned with the petulant nihilism of ‘Play It All Night Long’. It’s hard to think of an opening line more striking than ‘Grandpa pissed his pants again, he don’t give a damn’.

Oddly, the stripped down Flinch preceded the apotheosis of Zevon’s bizarre experimentation – 1995’s one-man-band studio album, Mutineer. Mangled processed guitars, twinkling music boxes, meandering synths and brittle drum machines. A woozy and centreless, 117 second cover of doomed ‘70s songstress Judee Sill’s ‘Jesus was a Cross Maker’? Flinch’s rollicking ‘Piano Fighter’ given a studio incarnation backed with chimes, accordion and no piano? How weird does it get? Try the stalking and queasy allusion of ‘Something Bad Happened To A Clown’.

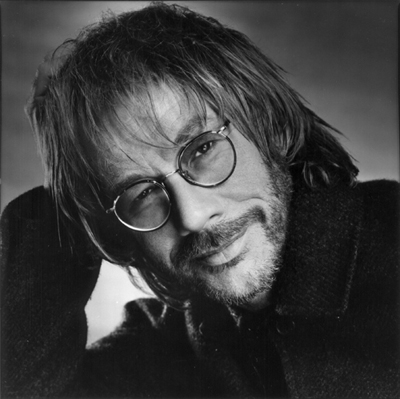

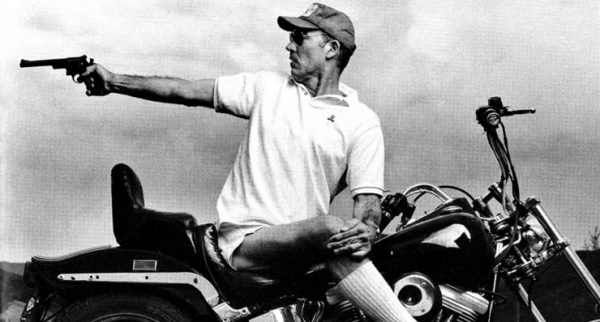

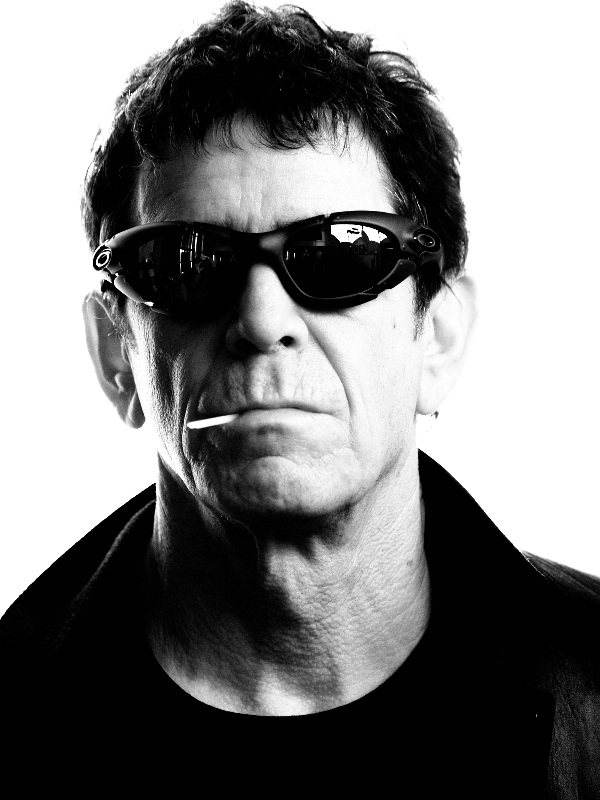

Warren Zevon & Hunter S. Thompson

Like novelist Martin Amis, the theme Zevon kept returning to was masculinity and violence. An embattled masculinity that was iconic as it recognised it was untenable. Reckless and paranoid, trapped and surly, drinking itself away. It’s best encapsulated in ‘Rottweiler Blues’’ flat refrain: ‘Don’t knock on my door if you don’t know my rottweiler’s name’. From Frank and Jesse James to boxer Ray ‘Boom Boom’ Mancini, from hockey goons and intrepid diplomatic envoys to the undead mercenary ‘Roland The Headless Thompson Gunner’, the Zevon catalogue is full of desperate aggression, given an extra edge with details from Zevon the political animal.

But there was the other side of Zevon’s songwriting. For every tale of S.W.A.T. raids and depraved debauchery there is an elegantly vulnerable, melancholically lost ballad. Long night of the soul music. Songs as beautiful as ‘The French Inhaler’ and ‘Accidentally Like A Martyr’. And Zevon was as fearless as his bravura characters in his squaring with these emotions. But whichever side of the coin he was occupying, it was always the man’s distinctively rich voice, that unmistakable personality. Whether raucous exuberance or luscious sorrow, the lyrics are always honed with dry wit and his fine intelligence. In synthesising these two sides, the bombastic ‘Lawyers, Guns and Money’ is the quintessential Zevon song. A perfect storm of Zevonian elements, our strong protagonist is backed into a corner as a result of drink, a woman and political circumstance, ensnared by a Soviet waitress after a night’s drinking in Cuba.

‘When the lights came up at two

I caught a glimpse of you

And your face looked like

Something Death brought with him in his suitcase’

– ‘The French Inhaler’ (1976)

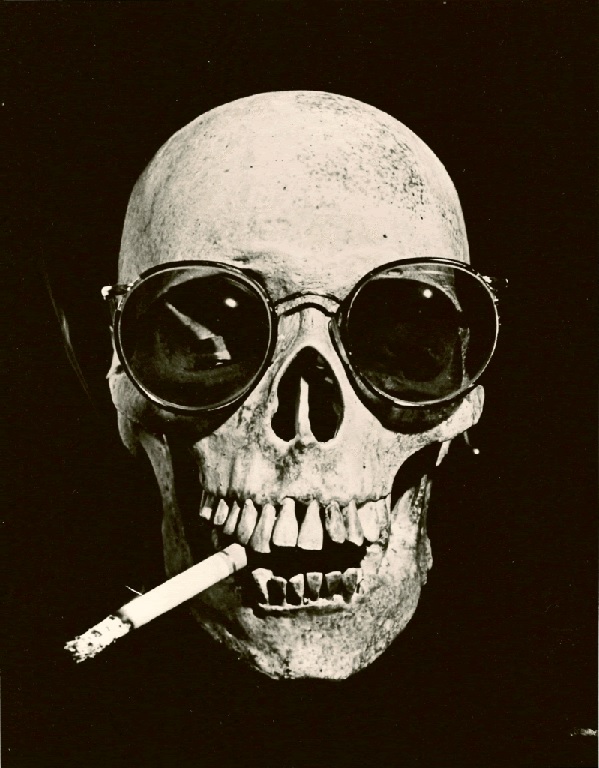

Paul Muldoon & Warren Zevon

The Zevonian humour of Warren’s diagnosis with mesothelioma in 2002 was that he couldn’t meet the news by making an album themed on death – he’d just released his second in a row with the excellent My Ride’s Here. This is, after all, a man who’d chosen a skull in shades smoking a cigarette as his logo. Still, as Jadakiss once noted, ‘You might find your man dead in the ocean/He be aight though, you know dead rappers get better promotion’, and the same seemingly held for dying songwriters. Like Amis’s close friend, the arch contrarian Christopher Hitchens, Zevon went out working, immediately setting to record his final album, The Wind. Springsteen, Jackson Brown, Tom Petty, Ry Cooder and a host of others stepped up to assist the recording of an album that is, in Zevonian tradition, uneven. It does feature amongst its gems though, the Eagles-assisted ‘She’s Too Good For Me’ – a song so great you could swallow your whole fist at the beauty of it. There was a VH1 documentary following the album’s recording, and later a tribute album, featuring Dylan, Pixies and Steve Earle among others; a truly no hold barred biography, written by Zevon’s ex-wife at his request; and, for those paying attention, a wealth of Zevon references in that most spiritually Los Angeles of shows, Californication. Most startling though was his final appearance on Letterman. Zevon had been a frequent Letterman guest over the years, even standing in as band leader in Paul Shaffer’s absence and having Letterman voice the irate hockey fan on ‘Hit Somebody! (The Hockey Song)’. Any fears the diagnosis might have cut down his humour were silenced as the dying Zevon walked out to the CBS Orchestra laying into a pounding rendition of his own ‘I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead’. When the subject was broached he grinned back, ‘Ya mean ya heard about the flu?’ The entire episode was given over to Zevon, for both a frank and heartfelt interview and touching performances. The martial camaraderie of ‘Roland”s barnstorming finale makes a hell of a last stand.

So here’s to a man who never shied away from digging deep into his heart, and venturing to the outer edge, for a song. He may not have been on this planet for a decade now, but the best of his songs could make you feel he was standing in the room. He once said of himself, ‘I’m insane. I’m fucked up. I have problems. But I don’t get depressed and I don’t get bored.’ Amen, brother. And remember – enjoy every sandwich.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

A Warren Zevon story nobody has heard until now … http://placeitonluckydan.com/2013/09/untold-warren-zevon/