One phrase that always infuriates me is ‘I wish I’d been around in [insert past decade here]. That’s when the music was great.’ There’s great music now! And far more avenues to find it easily than there’s ever been before! The belief that the great music has already passed is masochistic.

There are though two trajectories of musical quality. The first, and more widely familiar, is the ‘rock’ route. ‘At one point you’ve got it, and then you lose it.’ So postulates Johnny Lee Miller, wielding an air rifle as Trainspotting’s Sick Boy. Incorrect in terms of the specific example used (Lou Reed – New York for one is a genuinely great solo record) but broadly accurate. Successful rock bands generally strike a chord with the zeitgeist within their first couple of albums, possibly maintaining that prominent position for a few years before declining, maintaining a level of success with variations and retreads of their finest moment(s).

There are though two trajectories of musical quality. The first, and more widely familiar, is the ‘rock’ route. ‘At one point you’ve got it, and then you lose it.’ So postulates Johnny Lee Miller, wielding an air rifle as Trainspotting’s Sick Boy. Incorrect in terms of the specific example used (Lou Reed – New York for one is a genuinely great solo record) but broadly accurate. Successful rock bands generally strike a chord with the zeitgeist within their first couple of albums, possibly maintaining that prominent position for a few years before declining, maintaining a level of success with variations and retreads of their finest moment(s).

The other option is the ‘folk’ route. (This, counter-intuitively, is the route Motörhead have latterly followed.) There may be a little breakout success early on, getting the name out and launching a professional career, but success is built through heavy touring and cultivating a loyal fanbase; each album less an event around which to stage a tour so much as literally a record of that stage in the artist’s ongoing development.

Watching the late GG Allin’s appearance on Jerry Springer recently brought home the fact that, in the era of late capitalism, teenage rebellion needs to attach itself to something bigger than just hormones and a generation gap. Making out, going steady and riding in cars with boys are no longer the taboo-breaking acts of rebellion they were when rock and roll was first conceived. But if the enactment of life’s brutal reality through the breaking of noses, sexual assault and coprophagia in Allin’s shows seems needless and excessive, what, in this age of information and comfort, is there to rebel against?

Watching the late GG Allin’s appearance on Jerry Springer recently brought home the fact that, in the era of late capitalism, teenage rebellion needs to attach itself to something bigger than just hormones and a generation gap. Making out, going steady and riding in cars with boys are no longer the taboo-breaking acts of rebellion they were when rock and roll was first conceived. But if the enactment of life’s brutal reality through the breaking of noses, sexual assault and coprophagia in Allin’s shows seems needless and excessive, what, in this age of information and comfort, is there to rebel against?

If you’re not angry, then you’re just stupid, you don’t care (’90 – ’93)

What has Ani DiFranco rebelled against? What have you got. Ani DiFranco arrived, twenty years of age, on the cover of her eponymous 1990 debut, elegant, reflective and sporting that sorely underrated look of the shaved female head. (See also, a sphinx-like Cate Blanchett in Heaven; Samantha Morton’s psychic Agatha in Minority Report.) Ani DiFranco opens with ‘Both Hands’, and if you think you know a more beautifully sexual love song, go home, you’re drunk. ‘Lost Woman Song’ evenly levels a pro-choice stance while sexist objectification is indicted in ‘The Story’. This is a woman who’s going to mention menstruation. This is a singer who’s going to say ‘cunt’. The lyrics are poetically detailed, the voice beautiful, the songs full-bodied and the guitar playing in the aggressively percussive and accomplished style that would become a DiFranco trademark. Spoken poetry (‘The Slant’) and the fact pronouns of both genders are addressed, suggested pithy pidgeonholes like ‘lesbian folksinger’ would be far too narrow to encapsulate all of Ani.

What has Ani DiFranco rebelled against? What have you got. Ani DiFranco arrived, twenty years of age, on the cover of her eponymous 1990 debut, elegant, reflective and sporting that sorely underrated look of the shaved female head. (See also, a sphinx-like Cate Blanchett in Heaven; Samantha Morton’s psychic Agatha in Minority Report.) Ani DiFranco opens with ‘Both Hands’, and if you think you know a more beautifully sexual love song, go home, you’re drunk. ‘Lost Woman Song’ evenly levels a pro-choice stance while sexist objectification is indicted in ‘The Story’. This is a woman who’s going to mention menstruation. This is a singer who’s going to say ‘cunt’. The lyrics are poetically detailed, the voice beautiful, the songs full-bodied and the guitar playing in the aggressively percussive and accomplished style that would become a DiFranco trademark. Spoken poetry (‘The Slant’) and the fact pronouns of both genders are addressed, suggested pithy pidgeonholes like ‘lesbian folksinger’ would be far too narrow to encapsulate all of Ani.

Saphhic relationships, and the societal feeling around them, continued to be essayed in songs like ‘The Whole Night’, but so were abusive relationships (‘Fixing Her Hair’), the idolatrous elevation of artists (‘I’m No Heroine’) and abuses of power (the beautifully acapella ‘Every State Line’). Society’s need to neatly classify sexuality and gender is roundly refuted on ‘In Or Out’. Extensive, low-budget touring also gave DiFranco an atypically roving perspective, making observations from no fixed point and relying on the kindness of strangers in strange scenes.

Tell me, who’s your boogieman. That’s who I will be. (’94 – ‘97)

The lurid yellow cover of Ani’s fourth album Puddle Dive warned of brighter instrumentation but it was on the following Out Of Range that Ani made the ‘Judas’ move of folk singers: she went electric, emphasised by the two versions, acoustic and electric, of the frantic title track. She grew her hair. Her backing band had male members. Like Dylan and Billy Bragg before her, Ani didn’t separate the political from the personal. Bold and righteous statements didn’t come at the expense of personal vulnerability. The further two albums of Ani’s electric trilogy – Not A Pretty Girl and Dilate – are wrought dirges of anguish and bitter retribution. Ani’s attributed role as right-on spokesperson strikingly contrasts with the depths of her feeling in songs like ‘Superhero’.

The lurid yellow cover of Ani’s fourth album Puddle Dive warned of brighter instrumentation but it was on the following Out Of Range that Ani made the ‘Judas’ move of folk singers: she went electric, emphasised by the two versions, acoustic and electric, of the frantic title track. She grew her hair. Her backing band had male members. Like Dylan and Billy Bragg before her, Ani didn’t separate the political from the personal. Bold and righteous statements didn’t come at the expense of personal vulnerability. The further two albums of Ani’s electric trilogy – Not A Pretty Girl and Dilate – are wrought dirges of anguish and bitter retribution. Ani’s attributed role as right-on spokesperson strikingly contrasts with the depths of her feeling in songs like ‘Superhero’.

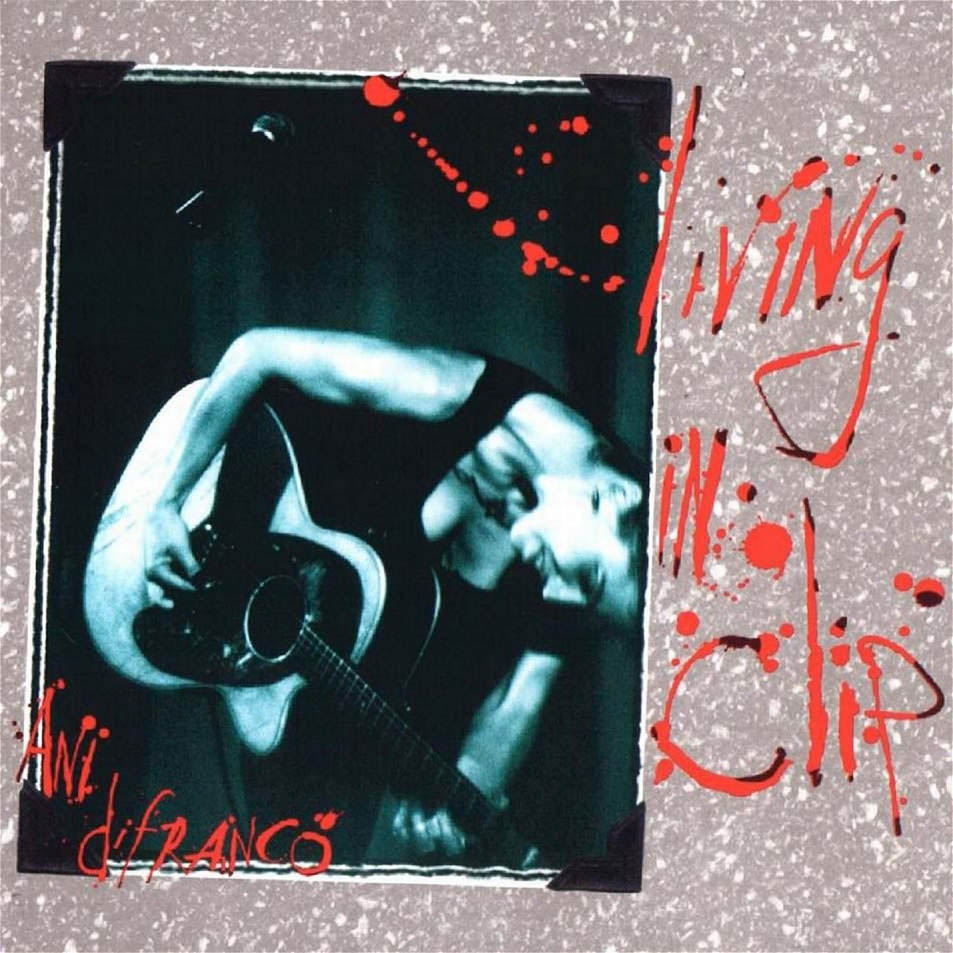

Even on the same album however there are surprises and indictments: in such an air of antiestablishmentarianism and unconvention, Ani delivers startling reworkings of ‘Amazing Grace’, while songs like ‘Letter to a John’ and ‘Hide and Seek’ offer strikingly matter-of-fact portrayals of sexual abuse and the attitudes leading to it. ‘Tiptoe’ revisits abortion while ‘Coming Up’ tackles the wealth inequality fostered by corporations. ‘Face Up And Sing’ exhorts the audience to contribute rather than just consume and ‘Napoleon’ lambasts the attitudes of large record companies. It should be mentioned that each of Ani’s records has been released on her own Righteous Babe Records, which she established to release her first record and now has a full roster of artists, as well as a 1,200 seat venue in Ani’s hometown of Buffalo, NY. An interlude on the subsequent Living In Clip live album answered the charge she’d sold out by ‘writing about like love and shit’ with simply ‘No, man – it’s just I got kind of distracted’.

Even on the same album however there are surprises and indictments: in such an air of antiestablishmentarianism and unconvention, Ani delivers startling reworkings of ‘Amazing Grace’, while songs like ‘Letter to a John’ and ‘Hide and Seek’ offer strikingly matter-of-fact portrayals of sexual abuse and the attitudes leading to it. ‘Tiptoe’ revisits abortion while ‘Coming Up’ tackles the wealth inequality fostered by corporations. ‘Face Up And Sing’ exhorts the audience to contribute rather than just consume and ‘Napoleon’ lambasts the attitudes of large record companies. It should be mentioned that each of Ani’s records has been released on her own Righteous Babe Records, which she established to release her first record and now has a full roster of artists, as well as a 1,200 seat venue in Ani’s hometown of Buffalo, NY. An interlude on the subsequent Living In Clip live album answered the charge she’d sold out by ‘writing about like love and shit’ with simply ‘No, man – it’s just I got kind of distracted’.

Taken out of context I must seem so strange (’98-’03; ’04-present)

The mariachi dawn of a title track that opens Ani’s eighth album, Little Plastic Castle, reiterates the attitudes that straying from the norm can face, but also emphasises that life doesn’t have to be so serious all the time. Little Plastic Castle begins a run of more experimental albums, with a greater emphasis on relationships, longer instrumental passages and instrumental songs, and a broader palette of instrumentation, rhythms and effects. Albums become longer, like the 29-track double album Revelling: Reckoning, and so do pieces like the incredible ‘Serpentine’ or the long 9/11 poem ‘Self-Evident’. These experiments aren’t always successful, and 1999’s To The Teeth is the first (and only) Ani album to sound like it was recorded just for the sake of making an album; a grim state of the union followed by pessimistic dirges. Who better though, to appear in a period of instrumental experimentation and attempting to redefine identity than the purple one himself, the then Artist Formally Known As Prince, who guests on To The Teeth and had Ani play guitar on his intended allstar comeback record, Rave Un2 The Joy Fantastic.

The mariachi dawn of a title track that opens Ani’s eighth album, Little Plastic Castle, reiterates the attitudes that straying from the norm can face, but also emphasises that life doesn’t have to be so serious all the time. Little Plastic Castle begins a run of more experimental albums, with a greater emphasis on relationships, longer instrumental passages and instrumental songs, and a broader palette of instrumentation, rhythms and effects. Albums become longer, like the 29-track double album Revelling: Reckoning, and so do pieces like the incredible ‘Serpentine’ or the long 9/11 poem ‘Self-Evident’. These experiments aren’t always successful, and 1999’s To The Teeth is the first (and only) Ani album to sound like it was recorded just for the sake of making an album; a grim state of the union followed by pessimistic dirges. Who better though, to appear in a period of instrumental experimentation and attempting to redefine identity than the purple one himself, the then Artist Formally Known As Prince, who guests on To The Teeth and had Ani play guitar on his intended allstar comeback record, Rave Un2 The Joy Fantastic.

Ani returned to a more recognisable form, though inevitably richer for her researches, with 2004’s Educated Guess. Her albums since have been album-length, with 2-3 minute songs, and again acoustic guitar based, albeit more comfortably pared back. This is not to say her convictions have lessened though, as her muscular reworking of the 1931 union folk song ‘Which Side Are You On?’ last year showed. The political criticism and explorations of the complexity of human relationships both remain, as do startling pieces like the remarkable ‘Parameters’ and the luscious, tender optimism of 2006’s Reprieve, while returning touches of experimentation suggest where DiFranco’s development might lead next.

Ani returned to a more recognisable form, though inevitably richer for her researches, with 2004’s Educated Guess. Her albums since have been album-length, with 2-3 minute songs, and again acoustic guitar based, albeit more comfortably pared back. This is not to say her convictions have lessened though, as her muscular reworking of the 1931 union folk song ‘Which Side Are You On?’ last year showed. The political criticism and explorations of the complexity of human relationships both remain, as do startling pieces like the remarkable ‘Parameters’ and the luscious, tender optimism of 2006’s Reprieve, while returning touches of experimentation suggest where DiFranco’s development might lead next.

And Ani continues to confound expectations. She’s married, divorced, and married again, giving birth to two children. The arrival of motherhood, prior to 2008’s Red Letter Day, slowed Ani’s touring and release rate, though – having released 15 studio albums in 17 years up to that point – only to the rate of normal mortals. And that’s not to mention her collaborations, production work and political activism; the albums she’s soundtracked for folk singer Utah Phillips and the volume of poetry she released in 2007 (which also included her paintings). Following the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, Ani and her family relocated to New Orleans.

Like lipstick is a sign of my declining mind

The point being made, of course, is not how positive a significance these choices have – whether you have short hair or blue braids; the sex of you or your partner; being willing to talk about issues and emotions – but rather that they should have no real significance at all. Like Allen Ginsberg’s poetry or the lyrics of the Wu-Tang Clan, Ani DiFranco’s songwriting takes in all aspects of life: the political and the emotional, the frivolities and details, mundanity and feats of imagination. Ani DiFranco has won so hard for so long, it makes most comparisons embarrassing, but the degree to which her achievements are daunting is balanced by her determination to encourage and inspire. Ani’s music portrays not one role but a whole human being, encouraging consciousness and engagement, politically and socially. Now, face up and sing.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe