‘Politics is the art of controlling your environment’ – Hunter S. Thompson

‘Bill Davis told me that he believes he is the hero of the show […] Whatever makes it easy for you to sleep at night, CSM.’ – David Duchovny

This article may well contain a few spoilers. But then, the show finished almost twelve years ago, so you’ve had your fair chance.

‘Watching X-Files with no lights on

We’re dans la maison

I hope the Smoking Man’s in this one’

– ‘One Week’, Barenaked Ladies

Cigarette Smoking Man. Cancer Man. Ol’ Smokey. That chain-smoking son of a bitch.

The run-up to the millennium was a time of stock-taking and deep reflection; of weighing the sum of our existence and facing the spectre of unknown unknowns. Riding the crest of this millennial angst and paranoia was Chris Carter’s The X-Files: a pair of plucky FBI agents daring to stick their faces into the occult and the shadowy world of a global conspiracy. There are mutations and psychopaths, spirits and alien abductions, but the real business, what Carter referred to as The X-Files’ ‘mythology’, was signalled by one man, originally merely a background character. The man who sat in on Mulder and Scully’s reporting to their superiors. The man at the heart of everything. A man lent silently against a filing cabinet, with Nixon jowls, a Raiders of the Lost Ark-style warehouse in the Pentagon, and a permanently smouldering cigarette.

The run-up to the millennium was a time of stock-taking and deep reflection; of weighing the sum of our existence and facing the spectre of unknown unknowns. Riding the crest of this millennial angst and paranoia was Chris Carter’s The X-Files: a pair of plucky FBI agents daring to stick their faces into the occult and the shadowy world of a global conspiracy. There are mutations and psychopaths, spirits and alien abductions, but the real business, what Carter referred to as The X-Files’ ‘mythology’, was signalled by one man, originally merely a background character. The man who sat in on Mulder and Scully’s reporting to their superiors. The man at the heart of everything. A man lent silently against a filing cabinet, with Nixon jowls, a Raiders of the Lost Ark-style warehouse in the Pentagon, and a permanently smouldering cigarette.

Don’t try and threaten me. I’ve watched presidents die.

Mulder and Scully faced a vast conspiracy, above any national government, engaged in actions withheld from the public. The face of this conspiracy was that of William B. Davis, cast as the ‘cigarette smoking man’. He would appear in locations all over the world: from wood-panelled boardrooms to underground parking garages, secure military bases to Antarctic research stations; in fields of corn in Tunisia to burning train carriages of alien corpses in the desert. He had squads of military personnel at his disposal; pioneering scientists, spies in every agency and a motley cadre of familiar and anonymous killers. Incidents and evidence are swept away, as if they never were, by his hand. Information would disappear and misinformation propagate at his will, as he walked the highest corridors of power. The world turns in the hidden palm of the Smokey Man’s machinations, and he is always calmer than the opponent pointing a pistol in his face, because he is used to swimming in these treacherous waters.

Mulder and Scully faced a vast conspiracy, above any national government, engaged in actions withheld from the public. The face of this conspiracy was that of William B. Davis, cast as the ‘cigarette smoking man’. He would appear in locations all over the world: from wood-panelled boardrooms to underground parking garages, secure military bases to Antarctic research stations; in fields of corn in Tunisia to burning train carriages of alien corpses in the desert. He had squads of military personnel at his disposal; pioneering scientists, spies in every agency and a motley cadre of familiar and anonymous killers. Incidents and evidence are swept away, as if they never were, by his hand. Information would disappear and misinformation propagate at his will, as he walked the highest corridors of power. The world turns in the hidden palm of the Smokey Man’s machinations, and he is always calmer than the opponent pointing a pistol in his face, because he is used to swimming in these treacherous waters.

Two instances encapsulate the balance of brutal efficiency and desperate humanity that is Smokey. One is the sight of him yelling ‘You saw nothing!’ at Mulder and Scully, as he dashes into a decommissioned North Dakotan nuclear missile silo, where he’s stashed a UFO. In the other, dropping cigarette ash over a bedridden and charred sailor, left scorched by high intensity radiation, Smokey instructs the doctor to have the bodies destroyed. When the doctor protests that the men aren’t yet dead, Smokey stares at him blankly: ‘Isn’t that the prognosis?’

Two instances encapsulate the balance of brutal efficiency and desperate humanity that is Smokey. One is the sight of him yelling ‘You saw nothing!’ at Mulder and Scully, as he dashes into a decommissioned North Dakotan nuclear missile silo, where he’s stashed a UFO. In the other, dropping cigarette ash over a bedridden and charred sailor, left scorched by high intensity radiation, Smokey instructs the doctor to have the bodies destroyed. When the doctor protests that the men aren’t yet dead, Smokey stares at him blankly: ‘Isn’t that the prognosis?’

I’m in the game because I believe what I’m doing is right.

In a show whose recurring motto, running through it like a stick of seaside rock, is ‘I Want To Believe’, Smokey unquestionably does. He is a believer. While the Syndicate – as the conspiracy’s leadership are known – will do whatever, and deal with whoever, to achieve their aims of control and survival, Smokey also believes wholly in the necessity of their actions; in the fact that humanity is unable to deal with the true reality, and must be lied to to prevent mass panic and collapse. Alone in his dingy apartments, over bottled beer and cigarettes, he watches old war movies and westerns, with their simple, stringent morality. While the Syndicate’s actions may be ruthless and coldly calculated, they will sacrifice for ‘the project’ when necessary. And are they a greater evil than the creeping ‘black oil’, and the threat of alien colonisation it brings?

In a show whose recurring motto, running through it like a stick of seaside rock, is ‘I Want To Believe’, Smokey unquestionably does. He is a believer. While the Syndicate – as the conspiracy’s leadership are known – will do whatever, and deal with whoever, to achieve their aims of control and survival, Smokey also believes wholly in the necessity of their actions; in the fact that humanity is unable to deal with the true reality, and must be lied to to prevent mass panic and collapse. Alone in his dingy apartments, over bottled beer and cigarettes, he watches old war movies and westerns, with their simple, stringent morality. While the Syndicate’s actions may be ruthless and coldly calculated, they will sacrifice for ‘the project’ when necessary. And are they a greater evil than the creeping ‘black oil’, and the threat of alien colonisation it brings?

The X-Files’ central tagline, and that of Mulder and Scully’s quest, was The Truth Is Out There. Smokey doesn’t disagree with the premise, only the response. As he bemoans at one point, ‘The truth was out there. Fatally exposed.’ Smokey’s forces amass in shadows to shield the truth, and smoking – Smokey’s Morley brand in particular – becomes a leitmotif running throughout the show for infection or corruption by conspiracy.

What would you like me to do? Shoot him dead? Splatter his brains?

Smokey, however, is no enthroned ruler. Increasingly he is revealed as a blunt tool of the Syndicate, dealing with unavoidable practicalities the other members have no stomach for. In his shabby suit and unkempt demeanour, Ol’ Smokey is less a supervillain than another blue collar worker getting his hands dirty; the workaday mundanity of evil. His clean-up measures often aren’t perfect, his security not infallible. He frequently lies to the Syndicate to maintain his reputation as they accuse him of ‘arrogance’ and ‘vague assurances’, disparaging his unrefined methods and attempting to cut him from the loop. Smokey is the conspiracy’s all too human face.

Smokey, however, is no enthroned ruler. Increasingly he is revealed as a blunt tool of the Syndicate, dealing with unavoidable practicalities the other members have no stomach for. In his shabby suit and unkempt demeanour, Ol’ Smokey is less a supervillain than another blue collar worker getting his hands dirty; the workaday mundanity of evil. His clean-up measures often aren’t perfect, his security not infallible. He frequently lies to the Syndicate to maintain his reputation as they accuse him of ‘arrogance’ and ‘vague assurances’, disparaging his unrefined methods and attempting to cut him from the loop. Smokey is the conspiracy’s all too human face.

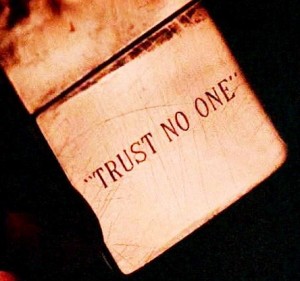

The only extensive background information we get on him comes in ‘Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man’. Here the story of his career is told, but fittingly only through an interpretation of a butchered fictionalisation written by Smokey himself, in his capacity as a frustrated writer of thrillers. He is portrayed as having influence in every aspect of distraction, from the Superbowl and the Oscars to the Olympics and media show trials. Saddam has his direct number. Recruited to assassinate JFK, all record of his life is erased. He becomes a force working outwith the knowledge of presidents; respects MLK but has to punish a perceived lean to communism. A frustrated author, a spy and an assassin, the Smokey Man is a sniper who writes the course of history. The inscription of ‘Trust No One’ across his lighter, just one more signifier of his shared perspectives with Mulder and Scully.

The only extensive background information we get on him comes in ‘Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man’. Here the story of his career is told, but fittingly only through an interpretation of a butchered fictionalisation written by Smokey himself, in his capacity as a frustrated writer of thrillers. He is portrayed as having influence in every aspect of distraction, from the Superbowl and the Oscars to the Olympics and media show trials. Saddam has his direct number. Recruited to assassinate JFK, all record of his life is erased. He becomes a force working outwith the knowledge of presidents; respects MLK but has to punish a perceived lean to communism. A frustrated author, a spy and an assassin, the Smokey Man is a sniper who writes the course of history. The inscription of ‘Trust No One’ across his lighter, just one more signifier of his shared perspectives with Mulder and Scully.

I’m here tonight as a friend, Agent Mulder.

As the passage of time clarifies perspective, it seems increasingly possible that the realest lines Joe Strummer ever wrote were ‘Death Or Glory’’s ‘I believe in this and it’s been tested by research/That he who fucks nuns will later join the church’. So it is that the starkly adversarial worlds of The X-Files’ conflict are found to be mutually permeable.

Not the wholly solitary figure suspected, Smokey – or C. G.B. Spender (‘An alias. One of hundreds.’) – is found to have both an ex-wife, Cassandra (whom he sacrificed to decades of medical testing, only for her to become a spokeswoman for organisations trying to expose him), and a son, Jeffrey (who he arranges to usurp Mulder, only to shoot and horrifically disfigure him when he disappoints).

Not the wholly solitary figure suspected, Smokey – or C. G.B. Spender (‘An alias. One of hundreds.’) – is found to have both an ex-wife, Cassandra (whom he sacrificed to decades of medical testing, only for her to become a spokeswoman for organisations trying to expose him), and a son, Jeffrey (who he arranges to usurp Mulder, only to shoot and horrifically disfigure him when he disappoints).

He also occupies the lives of the Mulder family. He worked with Mulder, Sr since the Roswell crash in ’47, and was his colleague in the Syndicate before ordering his assassination. He had a relationship with Mulder’s mother before Mulder was born, and cared for his sister after she was abducted. He saves Mrs Mulder’s life, arranges for Scully to be returned from abduction and at one point even cures her cancer! His influence holds sway over Mulder’s sphere, negatively and positively. In knowledge and experience, Smokey’s oppressive omnipotence is in some ways just that of an older generation over the next.

Each time it is repeated, the flimsy excuse of ‘Kill Mulder and you risk turning one man’s religion into a crusade’ highlights the number of escapes and acquitals Smokey allows Mulder. He repeatedly presumes Mulder’s death to avoid having to pursue him. Rather than its nemesis, Smokey’s minding makes him the creator of ‘the Mulder problem’.

You think I’m the devil?

A tv show jumps the shark when its focus crosses from situations, being experienced by the characters, to the characters themselves, and how they’d react to different situations. (If you want to know the exact moment The X-Files jumped the shark, that would be during S5E17, with the appearance of the actual devil, horns and all.) Smokey’s increasingly pantomime hysteric’s grin dances through The X-Files’ decline, from the moment he’s brought back from his lonely exile in a snow-isolated cabin in the Canadian woods, bare-chested and daring assassins to shoot him. He became such a towering figure, they were eventually forced to kill him off. Three times. Shot by a moustachioed Syndicate assassin (for failing to solve ‘the Mulder problem’), thereby becoming a victim of his own conspiracy. Thrown down the stairs by his demented, one-armed, endlessly double-crossed (and absurdly moisturised) aide, Alex Krycek. And then, for good measure, the subject of a missile strike – arranged by the conspiracy that supersedes the Syndicate – giving one last zen moment of exhaling cigarette smoke, facing down an attack helicopter, before the missile launches.

A tv show jumps the shark when its focus crosses from situations, being experienced by the characters, to the characters themselves, and how they’d react to different situations. (If you want to know the exact moment The X-Files jumped the shark, that would be during S5E17, with the appearance of the actual devil, horns and all.) Smokey’s increasingly pantomime hysteric’s grin dances through The X-Files’ decline, from the moment he’s brought back from his lonely exile in a snow-isolated cabin in the Canadian woods, bare-chested and daring assassins to shoot him. He became such a towering figure, they were eventually forced to kill him off. Three times. Shot by a moustachioed Syndicate assassin (for failing to solve ‘the Mulder problem’), thereby becoming a victim of his own conspiracy. Thrown down the stairs by his demented, one-armed, endlessly double-crossed (and absurdly moisturised) aide, Alex Krycek. And then, for good measure, the subject of a missile strike – arranged by the conspiracy that supersedes the Syndicate – giving one last zen moment of exhaling cigarette smoke, facing down an attack helicopter, before the missile launches.

I’m a necessity. My work is just beginning.

In the wake of the Syndicate’s demise, and in light of the revelations of Snowdon and PRISM, perhaps focus should have turned to one of the characters floated to fill Ol’ Smokey’s shoes: the moustachioed Shadow Man (played by Lost’s Terry O’Quinn in a typical act of X-Files double-casting, he already having died as a compromised FBI bomb disposal expert in the X-Files film). From within his inconspicuous surveillance bunker, the Shadow Man monitors every aspect of citizens’ lives, through constant, unconstitutional observation of their electronic communications, phonecalls and appearances on CCTV. But then again, if we look too closely, maybe we’d see conspiracies everywhere. For example, have you ever noticed that whenever Mulder and Scully had issues with local law enforcement, one of the team always had a moustache? Always.

In the wake of the Syndicate’s demise, and in light of the revelations of Snowdon and PRISM, perhaps focus should have turned to one of the characters floated to fill Ol’ Smokey’s shoes: the moustachioed Shadow Man (played by Lost’s Terry O’Quinn in a typical act of X-Files double-casting, he already having died as a compromised FBI bomb disposal expert in the X-Files film). From within his inconspicuous surveillance bunker, the Shadow Man monitors every aspect of citizens’ lives, through constant, unconstitutional observation of their electronic communications, phonecalls and appearances on CCTV. But then again, if we look too closely, maybe we’d see conspiracies everywhere. For example, have you ever noticed that whenever Mulder and Scully had issues with local law enforcement, one of the team always had a moustache? Always.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe