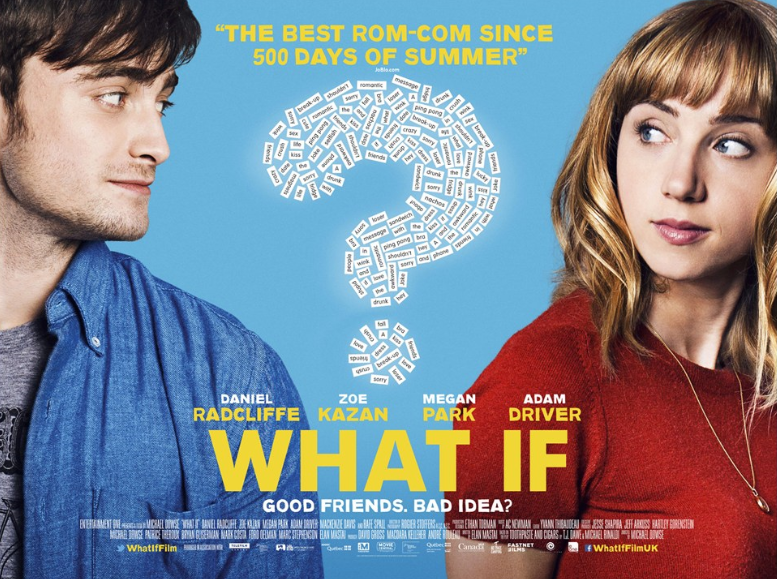

I recently saw What If (also known as The F Word) at the cinema. It was a predictable and silly indie rom-com. I didn’t think much of it, but it did get me thinking about the difference between the slick, totally-cheeseball Hollywood romantic comedies and those that are born out of more independent minds. The problem with What If was not necessarily that it was predictable, but because it was an indie rom-com. As a result of this status, I expected more of it. If it had been (or even simply marketed as) a mainstream rom-com instead of an indie film, it would probably have been exactly what I had expected – not a disappointment, just a staple of the standard rom-com genre.

My feelings of disappointment for What If were a result of my expectations going in – expectations surrounding independent films and more specifically, indie rom-coms. But what exactly are these expectations and where do they come from?

What is an independent film?

You might think the name of the thing is self-explanatory, and to an extent it is. But it is worth noting that to qualify as an ‘independent film’, it can still have some ties to the major film studio system. Independent films are produced either entirely or mostly outside of big Hollywood. As such, Star Wars was technically an independent film. Distribution of independent films usually does take place within the major studio system, or at least by a subsidiary of a major film studio. Otherwise, release of an independent film will be rather limited. This has, of course, changed slightly since releasing films online has gained in popularity.

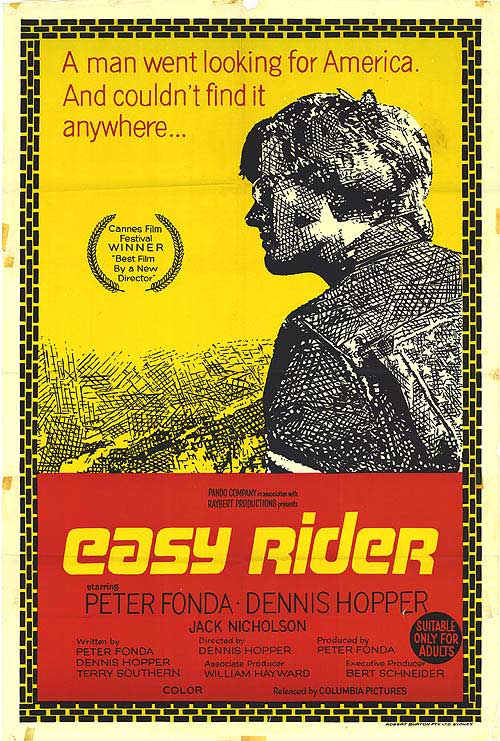

Independent films are not a new concept. Back in the 1960’s, George Romero was making full use of the independent system to shock and terrify audiences with his independent horror films while more mainstream Hollywood types were turning to independent funds to make road (Easy Rider) and crime (Bonnie and Clyde) films. After the US Film Festival was renamed the Sundance Film Festival in 1991, there was a resurgence in popularity of independent films, with many premiering at the festival as a way of securing wider distribution from major studios. Writers and directors such as Steven Soderbergh, Robert Rodriquez, Quentin Tarantino, and David O. Russell found success with their films through this route.

Independent films are not a new concept. Back in the 1960’s, George Romero was making full use of the independent system to shock and terrify audiences with his independent horror films while more mainstream Hollywood types were turning to independent funds to make road (Easy Rider) and crime (Bonnie and Clyde) films. After the US Film Festival was renamed the Sundance Film Festival in 1991, there was a resurgence in popularity of independent films, with many premiering at the festival as a way of securing wider distribution from major studios. Writers and directors such as Steven Soderbergh, Robert Rodriquez, Quentin Tarantino, and David O. Russell found success with their films through this route.

As the price of filmmaking equipment reduced in price, more and more independent studios and filmmakers tried to make their mark. In addition, crowd sourcing (such as Kickstarter) has made it possible for almost anyone to fund a project of their own. It is still difficult to find funding on anywhere near the levels that Hollywood studios put up for their films. As a result, many independent films are set in contemporary times with limited sets/locations to keep costs down. This is why you rarely (although you do sometimes) see independent historical, science fiction, or fantasy films.

It’s all about style: Indie films as a genre of their own

While the term ‘independent film’ refers to how a film’s funds were raised and what company produced it, it has come to mean a lot more than that. Over the years, indie films have developed their own signature style. This style is predominantly quirky and tends to hit audiences much harder in the ‘feels’ than a traditional Hollywood film. Focus Features (the ‘indie’ arm of NBCUniversal), for instance, one of the bigger indie film production companies, makes film after film that’s meant to hit hard on real emotions. And for the most part, they do.

While the term ‘independent film’ refers to how a film’s funds were raised and what company produced it, it has come to mean a lot more than that. Over the years, indie films have developed their own signature style. This style is predominantly quirky and tends to hit audiences much harder in the ‘feels’ than a traditional Hollywood film. Focus Features (the ‘indie’ arm of NBCUniversal), for instance, one of the bigger indie film production companies, makes film after film that’s meant to hit hard on real emotions. And for the most part, they do.

Arguable, what makes indie films so much better at getting to the heart of an issue is that they have a tendency to feature characters we don’t see elsewhere. Some might say that the characters are unusual, but really, aren’t we all unusual? It’s nice to see oddballs and screw-ups on screen. Hey, Hollywood, guess what… we don’t all look like supermodels with perfect skin, hair and teeth, we are real people with real problems and every so often it’s nice to see that reflected in cinema. Of course, then there’s the other side of it, sometimes it’s nice to see the completely bizarre – especially when a talented writer/director actually makes you sympathise with characters and stories you never thought you would (take Harold and Maude, for instance).

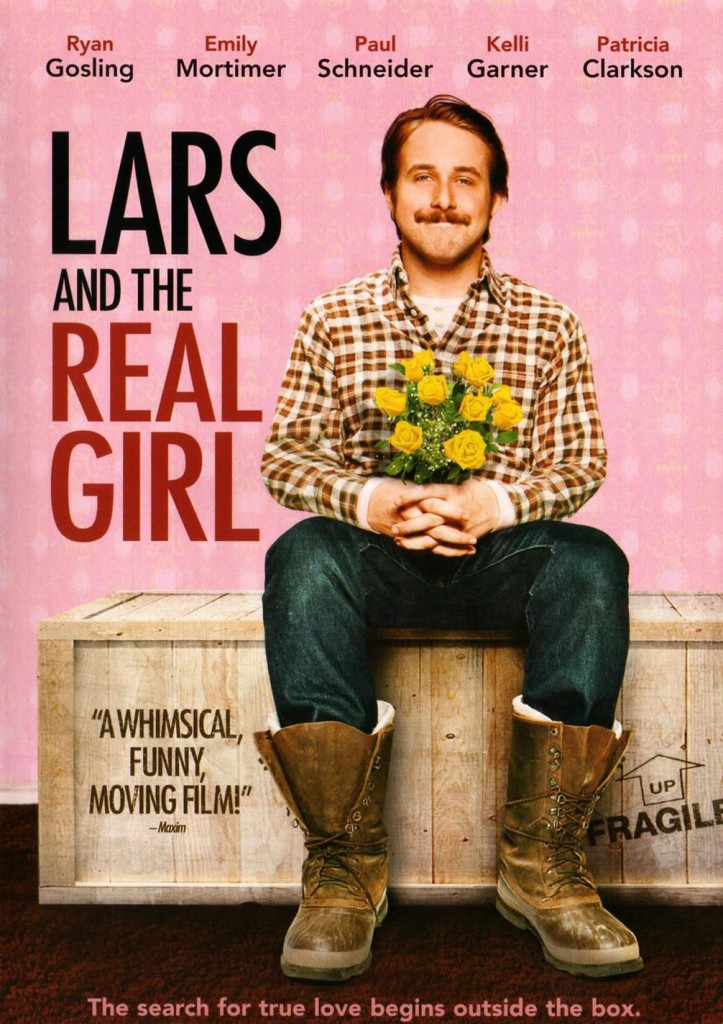

Quirky, different characters generally leads to diverse subject matter as well. One of my favourite indie rom-coms is Lars and the Real Girl (2007). The story touches on a socially awkward young man trying to navigate his way through life and finding it easier to form a relationship with an anatomically correct doll rather than a living, breathing woman. What’s so great about the film is the way that it undermines the usual connotations with sex dolls and instead focuses on real personality disorders and mental illness. Similarly, Secretary (2002), is a beautiful romance story about a couple who enjoy BDSM. I think 50 Shades of Grey could learn a lot from it.

Quirky, different characters generally leads to diverse subject matter as well. One of my favourite indie rom-coms is Lars and the Real Girl (2007). The story touches on a socially awkward young man trying to navigate his way through life and finding it easier to form a relationship with an anatomically correct doll rather than a living, breathing woman. What’s so great about the film is the way that it undermines the usual connotations with sex dolls and instead focuses on real personality disorders and mental illness. Similarly, Secretary (2002), is a beautiful romance story about a couple who enjoy BDSM. I think 50 Shades of Grey could learn a lot from it.

So where did What If go wrong?

Daniel Radcliffe has long been a supporter of independent cinema, and for good reason. But he had a bit of a misstep being involved with this one. I’m not saying it was truly awful. After all, it is a romantic comedy – when you know that going in, it is impossible to simply say that is was ‘predictable’ when that is kinda the point – the girl and the boy (or boy and boy/girl and girl…) end up together (or it wouldn’t be a romantic comedy, right?!). The problem was that the characters themselves were predictable: twenty-somethings unsure of what to do with their lives. They could have come from any Hollywood film.

The performances were good. Daniel Radcliffe was a nice mix of pathetic and likeable while Adam Driver stole the show (again) as his best friend. Zoe Kazan is alright, she delivers everything perfectly fine, but she doesn’t really have any great personality leap off the screen (in this or in In Your Eyes). But none of the characters are different, with truly interesting issues, and the subject matter is completely ordinary. Perhaps this is because of the idea I (along with many others) have formed on what an indie film should be, but this one just didn’t have enough of anything – charm, quirkiness, or star turns – to make it worth the trip to the cinema.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe