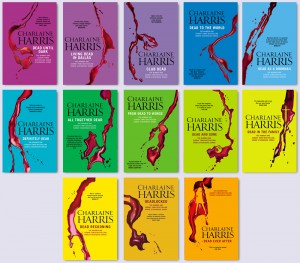

Since 1981, Charlaine Harris has published almost 40 novels. She is most well known for her Southern Vampire Mystery Series featuring Sookie Stackhouse, on which the HBO series True Blood was based. She has created five other series, all of which have been commercially successful. The Midnight, Texas series is the series she is currently working on, having published the first installment in 2014, Midnight Crossroad. The second in the series, Day Shift, is due to be published on May 5th. This is my first time reading any Charlaine Harris. And while it is the second installment of a series, the novel is very self-contained. Her works are known to be easy to pick up, even out of order – it makes them great for airport bookshops.

I had not finished the prologue before I knew I would not get on with this novel. Despite having been a professional writer for over 30 years, Harris hasn’t managed to get past rookie mistakes, nor has she developed an interesting voice. Exposition is delivered in dull, matter of fact terms, the dialogue rarely has a point beyond stating the absolute obvious or regurgitating information we already knew but may have forgotten, and the characters are so two-dimensional I have to wonder if Harris actually knows any real people at all. And the mystery? Neither mysterious or original.

I had not finished the prologue before I knew I would not get on with this novel. Despite having been a professional writer for over 30 years, Harris hasn’t managed to get past rookie mistakes, nor has she developed an interesting voice. Exposition is delivered in dull, matter of fact terms, the dialogue rarely has a point beyond stating the absolute obvious or regurgitating information we already knew but may have forgotten, and the characters are so two-dimensional I have to wonder if Harris actually knows any real people at all. And the mystery? Neither mysterious or original.

A one-horse, supernatural town

Like her other tales, Harris’s Day Shift is a mystery. The novel is set in the tiny town of Midnight, Texas, where strange and supernatural characters live in isolation for protection from the curious and unbelieving.

Manfred Bernado is a psychic. He drives to Dallas for a weekend of one-on-one appointments with clients when one of them, Rachel Goldthorpe, dies while in session with him. Her unstable son Lewis accuses Manfred of stealing his mother’s jewels and taking advantage of a gullible old woman. As the case heats up, reporters come to Midnight, threatening to uncover some of the town’s other secrets.

Manfred Bernado is a psychic. He drives to Dallas for a weekend of one-on-one appointments with clients when one of them, Rachel Goldthorpe, dies while in session with him. Her unstable son Lewis accuses Manfred of stealing his mother’s jewels and taking advantage of a gullible old woman. As the case heats up, reporters come to Midnight, threatening to uncover some of the town’s other secrets.

As Manfred and the town’s inhabitants are dragged further into the case of Rachel Goldthorpe’s missing jewels, they find themselves in increasing hot water. Rachel didn’t die of natural causes after all; she was murdered.

Making the case for creative writing courses

There are plenty of arguments to say that creative writing courses aren’t a good idea, but honestly, reading this novel shows just how valuable they can be. So many of the mistakes – yes, I am confident to straight up call them mistakes – made by Harris are the elementary pieces that any decent writing course would tell you to avoid. Exposition dumps, pointless dialogue that neither drives the plot or expands on character, and repetition so condescending as to assume the reader is a complete moron… these are beyond rookie mistakes. And to make them after so many published novels – hugely successful novels at that – is thoroughly depressing.

There are plenty of arguments to say that creative writing courses aren’t a good idea, but honestly, reading this novel shows just how valuable they can be. So many of the mistakes – yes, I am confident to straight up call them mistakes – made by Harris are the elementary pieces that any decent writing course would tell you to avoid. Exposition dumps, pointless dialogue that neither drives the plot or expands on character, and repetition so condescending as to assume the reader is a complete moron… these are beyond rookie mistakes. And to make them after so many published novels – hugely successful novels at that – is thoroughly depressing.

If you don’t believe me, here’s an example of entirely pointless – and thoroughly boring exchange of dialogue:

Manfred glanced at the clock he kept on the desk. “Yes, I can make it,” he said. “Headquarters of the Bonnet Park police?”

“Yes, right, need the address?”

“Thanks.” Manfred scribbled it down. “I’d better get started.”

“No problem,” said the obliging Phil. “Hope all goes well.”

Then there’s the dialogue that is purely expositional, even if it does simply build on whatever has already been brought to the reader’s attention several times already:

Instead, she said, “I guess I can hardly be a big skeptic since I sleep with an energy-draining vampire.”

And in case your memory is beyond hope, there are handy recaps of every major event in both the descriptive prose and dialogue. Plot points are recounted again and again to any character who didn’t happen to be in attendance, and even sometimes to those that were. On occasion, one character even summarizes what has literally JUST HAPPENED in a block of expositional dialogue. Something the author clearly recognizes as overkill, as another character even comments on this by saying “That’s a good summary.”

And in case your memory is beyond hope, there are handy recaps of every major event in both the descriptive prose and dialogue. Plot points are recounted again and again to any character who didn’t happen to be in attendance, and even sometimes to those that were. On occasion, one character even summarizes what has literally JUST HAPPENED in a block of expositional dialogue. Something the author clearly recognizes as overkill, as another character even comments on this by saying “That’s a good summary.”

Harris also seems to think that readers need to know exactly what every character is doing as and when they do it, and that plans need to be detailed out before they take place as blow-by-blow accounts. The entire thing reads like a poor news article or perhaps a witness statement for a court, never leaving any detail out, even what they had for breakfast that morning or where they sat when they ate it. For instance:

“Say we leave here day after tomorrow at nine. We’ll have to stop at least once, because they’ll have to pee. We get to Dallas, take them to a Golden Corral or an Outback or something, and then go to Bonnet Park. We’ll get to the Goldthorpe house between one and two, give or take. And we’ll spend about an hour there. We should be able to have them back by dinner.”

Perhaps the poor prose could be forgiven if the characters were interesting and/or the plot intriguing. Sadly, the ‘mystery’ was so obvious it didn’t drive me to read on and the characters were so completely lacking in personality that they were mostly known by their jobs or their supernatural abilities. There were references to Harris’s other series, trying to pull all her work into the same universe, but these references were labored, obvious, and pointless.

Perhaps the poor prose could be forgiven if the characters were interesting and/or the plot intriguing. Sadly, the ‘mystery’ was so obvious it didn’t drive me to read on and the characters were so completely lacking in personality that they were mostly known by their jobs or their supernatural abilities. There were references to Harris’s other series, trying to pull all her work into the same universe, but these references were labored, obvious, and pointless.

Verdict: This book was simply awful. Unless you’re looking for a handy guide of what not to do when writing a novel, avoid at all costs.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe