There has been a recent spate of reviews and discussions of this novel popping up on sites I read. When I was wandering around my local bookshop, I spotted it on a recommended pile and couldn’t resist. Now that I have fallen utterly in love with We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Shirley Jackson’s last novel, I understand why I there were countless glowing reviews.

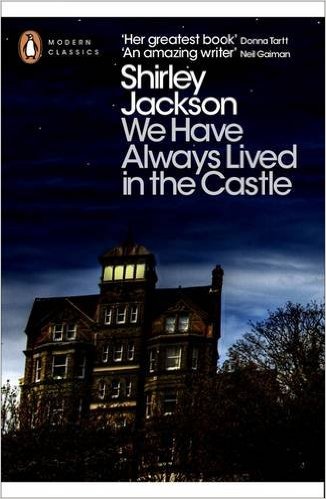

I’ve not always been the best reader of ‘classic’ novels. Many of them I find dull, overwritten, and focusing entirely too much on ‘pretty’ prose rather than developing interesting characters, plots, or trying to establish a pace that isn’t completely snore-inducing. I’ve become an unusual sort of reverse snob – if a book appears on a ‘classics’ imprint, I’ll usually avoid it, assuming it falls into the category of stuffy, dull, pretentiousness. We Have Always Lived in the Castle is far from my (possibly) unfair generalisations, so am glad I managed to move past my prejudice and pick up the latest Penguin Classics edition.

Merricat Blackwood lives on the family estate with her sister Constance and her uncle Julian. Not long ago there were seven Blackwoods—until a fatal dose of arsenic found its way into the sugar bowl one terrible night. Acquitted of the murders, Constance has returned home, where Merricat protects her from the curiosity and hostility of the villagers. Their days pass in happy isolation until cousin Charles appears. Only Merricat can see the danger, and she must act swiftly to keep Constance from his grasp.

Merricat Blackwood lives on the family estate with her sister Constance and her uncle Julian. Not long ago there were seven Blackwoods—until a fatal dose of arsenic found its way into the sugar bowl one terrible night. Acquitted of the murders, Constance has returned home, where Merricat protects her from the curiosity and hostility of the villagers. Their days pass in happy isolation until cousin Charles appears. Only Merricat can see the danger, and she must act swiftly to keep Constance from his grasp.

The creepiness of real life

‘Everyone else in our family is dead.’

What a wonderful premise for a creepy novel – there are three Blackwood’s left and one of them killed all the others. The novel’s narrator, Merricat Blackwood, is an archetypal unreliable narrator in many ways, while in others she completely breaks convention. This isn’t the kind of story where the reader believes she is sane and trustworthy but that trust is eroded over time – quite the contrary. Almost immediately, it is obvious she is not to be trusted and yet we still do trust her. Her voice is intoxicating. It draws the reader in and makes us complicit in Merricat’s bizarre behaviour. We want to keep Constance safe, keep her from the world; we hate the villagers and wish death in their food; we want the house to be free of evil.

Being so grounded in the potentially real, the novel’s plot is terrifyingly believable. Like the exquisite thriller Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, also released in 1962, the novel delves into mental illness in a very direct manner. Constance’s decision to shut herself away from the world is entirely understandable after the death of her family, incarceration, subsequent trial, and the vitriol from her neighbours.

‘I can’t help it when people are frightened,’ says Merricat. ‘I always want to frighten them more.’

And who is the more mentally damaged, Constance or Merricat? Perhaps Merricat has driven Constance over the precipice, but Merricat is far more aware of what she is doing than her older sister, something that is never more obvious than when gold-digging cousin Charles comes to visit. It is Merricat who sees through his act to the true nature of his visit.

The prescience of the unhinged

‘When Jim Donell thought of something to say he said it as often and in as many ways as possible, perhaps because he had very few ideas and had to wring each one dry.’

Surprisingly – or perhaps it is apt – Merricat is very observant and in tune with the world around her. Unlike her withdrawn sister, Merricat understands the villagers and what they would do to the Blackwoods if they could. Her visits into the town show this well – she has a routine that she does not deviate from. The route is planned and as short as possible, her interactions all a necessity – even the social interaction at the coffee shop. Merricat knows that if she is able to keep up a modicum of ‘normalcy’ with the outside world, the threat to the Blackwoods reduces.

Each of the Blackwoods has their own mental handicap – Constance with her naiveté and agoraphobia, Merricat’s psychosis, and Uncle Julian’s confusion and memory troubles – and in turn each enables the other’s issues. For instance, Constance allows Merricat’s fantasies to continue while Merricat keeps Constance shielded from the real world. Even when the truth of the family’s demise is revealed, the reader is left wondering if anyone is to blame over and above anyone else. Has Merricat driven Constance to be so afraid of the outside world or did Constance’s fears lead Merricat into the role of fanciful protector?

‘I really think I shall commence chapter forty-four,’ he said, patting his hands together. ‘I shall commence, I think, with a slight exaggeration and go on from there into an outright lie. Constance, my dear?’

‘Yes, Uncle Julian?’

‘I am going to say that my wife was a beautiful woman.’

I am still not sure what We Have Always Lived in the Castle is, in terms of genre. Is it a thriller? Mystery? Horror? Realist drama? All of the above? It is surreal, fantastical, and ordinary all at once. I have been able to conclude, however, that the novel is entrancing. It is the kind of novel that is endlessly quotable and should be held up as an example to all budding novelists.

Verdict: READ. THIS. BOOK.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe