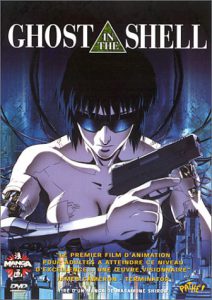

Ahead of the alternately anticipated or dreaded live-action version, this week saw the re-release in cinemas of Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell. The film is a landmark in world and animated cinema, spawning a host of imitators and is, for the record, one of my favourite films.

The film first arrived in 1995. Based on the manga by Masamune Shirow, Ghost in the Shell was part of a wave of relatively high-profile anime productions that ventured further abroad from the late 1980s through to the 1990s. Ghost in the Shell built on the market opening created by trailblazer Akira back in 1988 to further secure the channel for mature and artistic Japanese animation to reach overseas audiences. It was also, appropriately for a film steeped in the impact of technology, an early implementer of CGI elements in its animation, preceding Miyazaki’s use of it in Princess Mononoke (1997) and on the heels of Disney who had started to do so in 1991 with Beauty and the Beast.

The influence of this film echoes throughout modern cinema

Interesting as these behind the scenes factors are, what sets Ghost in the Shell apart is how characterful and distinct it feels even now. The wilfully cerebral plot involves a rather convoluted investigation of a governmental black flag operation but this is more a context for exploring the rich themes of the piece. In its definitive cyberpunk setting where the networked and cyborg society has not yet dissolved ‘nation and race’ (as the title card tells us), Major Motoko Kusanagi experiences the steady loss of identity. The potential of technology in the film, where humans can interact remotely across digital platforms and enhance their bodies with all kinds of appendages and advancements, allows for ever expanding forms of consciousness. But for someone like the Major who is so heavily cybernetic, old models of identity and consciousness cease to be functional.

Interesting as these behind the scenes factors are, what sets Ghost in the Shell apart is how characterful and distinct it feels even now. The wilfully cerebral plot involves a rather convoluted investigation of a governmental black flag operation but this is more a context for exploring the rich themes of the piece. In its definitive cyberpunk setting where the networked and cyborg society has not yet dissolved ‘nation and race’ (as the title card tells us), Major Motoko Kusanagi experiences the steady loss of identity. The potential of technology in the film, where humans can interact remotely across digital platforms and enhance their bodies with all kinds of appendages and advancements, allows for ever expanding forms of consciousness. But for someone like the Major who is so heavily cybernetic, old models of identity and consciousness cease to be functional.

Ghost in the Shell is overtly and proudly philosophical. As much as it deals with the hard-nosed cops of Section 9 who head up a cyber-terrorism task force, it sees no reason why these battle-hardened professionals should not be able to confront dense philosophical issues. The actions of the ‘antagonist’ (if he can truly be called such) The Puppet Master are not motivated by the objectives of shady political institutions but by a desire to reach his potential in this unstable medium of existence.

Like all the greatest cinema, the film never falls neatly into established templates or formulas

Cyber-terrorist action-drama with philosophical overtones is one thing, but I doubt Ghost in the Shell would be remembered as fondly if its depth was not matched by the richness of its production in all levels. The animation, even where it uses dated conceptions of computer technology, holds up really well. The detail of the figures even as they flow through intricate and carefully choreographed movement is beautiful. The scenery and backgrounds are awe-inspiring – so much so that the scenery artwork makes up the best sequence of the film when the audience is exposed to the sprawling consciousness of the cybernetic city.

Cyber-terrorist action-drama with philosophical overtones is one thing, but I doubt Ghost in the Shell would be remembered as fondly if its depth was not matched by the richness of its production in all levels. The animation, even where it uses dated conceptions of computer technology, holds up really well. The detail of the figures even as they flow through intricate and carefully choreographed movement is beautiful. The scenery and backgrounds are awe-inspiring – so much so that the scenery artwork makes up the best sequence of the film when the audience is exposed to the sprawling consciousness of the cybernetic city.

If any one section were to represent the film though, it would be the notorious ‘Making of a Cyborg’ sequence of the film’s opening. Overlaid with Kenji Kawai’s eerie score (his soundtrack for the film is surely one of the greatest ever recorded), we see the Major’s body constructed. From cybernetic brain casing through the artificial musculature to the final naked form, Oshii establishes the clear divide between a normal human and the necessarily mediated and artificial existence the Major experiences. Kawai’s opening theme uses old Japanese chanting with a Bulgarian folk harmony to convey a weird religiosity to the event. This is almost a sacred ritual as much as an assembly process. The chant is in fact an ancient wedding song – perhaps suggesting the idea of human becoming wed with machine.

Ghost in the Shell remains an ambitious, beautiful and poignantly intelligent film that has held up to repeat viewings for me again and again. Any chance to see it on the big screen is more than relished.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe