This cult classic courted controversy when it was first released for its ‘vulgar violence’. It was rated R in its home country of Japan and was either banned or found only limited releases in other countries. Watching it now, I find this baffling. Yes, it is violent, but worse than many others widely released? If anything, the violence of Battle Royale is caricatured by the bright colour and watery consistency of the fake blood, making it far more palatable (for me, at least) than many more realistic onscreen depictions of gore and violence.

Despite the hiccups on release, Battle Royale was welcomed by audiences and critics. The film, and the book upon which it was based, long preceded Suzanne Collins’ smash success The Hunger Games. Though the premises for each are very similar, Collins has always denied any knowledge of Battle Royale from when she wrote the first novel. Once you take the time to see Battle Royale, you will likely feel as I do – that The Hunger Games, while still thoroughly enjoyable, is a poor imitation of a brilliant and original tale.

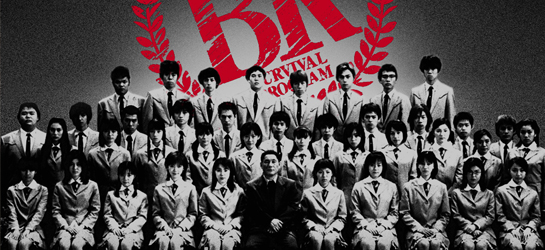

The film follows a 9th grade class ‘randomly’ selected to take part in the year’s Battle Royale – a brutal game where students must kill each other until there is only one left. The game was put in place after a mass student strike and anger between the adults and youths of Japan. These students have known each other for years, they are friends, enemies, lovers… and they are forced to kill one another. Teenage anxieties and competitiveness are heightened to breaking point as the students attempt to survive 3 days of extreme violence, suspicion, and gaming the game makers.

‘When we escape, it will be together.’

The film techniques used in Battle Royale make for a very different cinematic experience to Western cinema. Having a limited view of Asian cinema, I can’t comment on whether these are common techniques for the region or if they are peculiar to the film. Two notable differences I want to draw attention to is the number of red herrings and fake-outs used as well as the shifting narrative p.o.v.

The film techniques used in Battle Royale make for a very different cinematic experience to Western cinema. Having a limited view of Asian cinema, I can’t comment on whether these are common techniques for the region or if they are peculiar to the film. Two notable differences I want to draw attention to is the number of red herrings and fake-outs used as well as the shifting narrative p.o.v.

The film opens with a tattered and bloody girl, grinning at the cameras and swarms of curious people. She is the winner of the Battle Royale competition and she is smiling – why? The theme of the curious smile runs throughout the film, but that is not the piece most interesting here. This opening serves as a way to establish exposition – this is not the first or only time the game is being played. Whether this girl is the winner of a game in the past or one in the future, we don’t know, but we can see that the game is a big deal to the general public in Japan. But am I the only one who found this to also be a red herring in itself? I spent much of the first half-hour of the film trying to find the girl with the braces and demented smile to see who would be the victor until finally realizing that the opening scene was not from the story we were being told.

With so many characters, the film has multiple narrative threads. While this makes the film interesting to watch, it serves a story purpose. There are several different groups who could potentially ‘win’ the game or find a way to outmaneuver it. The filmmakers use this to play with the audience, throwing potential endings at them until the viewer will stop trying to guess at how it will all end. For instance, Mimura and his friends hack into the game’s computer system, rendering much of the equipment useless. This feels as though the tide of the game is changing, that those left in the game will rise up against the unfairness of the situation. But this hope is quickly crushed, with the rebels being cut down almost as soon as they ‘overthrow’ the system.

With so many characters, the film has multiple narrative threads. While this makes the film interesting to watch, it serves a story purpose. There are several different groups who could potentially ‘win’ the game or find a way to outmaneuver it. The filmmakers use this to play with the audience, throwing potential endings at them until the viewer will stop trying to guess at how it will all end. For instance, Mimura and his friends hack into the game’s computer system, rendering much of the equipment useless. This feels as though the tide of the game is changing, that those left in the game will rise up against the unfairness of the situation. But this hope is quickly crushed, with the rebels being cut down almost as soon as they ‘overthrow’ the system.

Similarly, the ending is not a straightforward affair. There are several fake-outs, where the viewer thinks they know what has happened, but the rug is swiftly pulled out from under them. And it keeps happening, several times over. It makes for a stressful viewing experience at times – you are always on your feet and can’t relax. It is certainly a unique way of creating a kind of meta-textual tension to build on the narrative tension already well established.

‘Life is a game. So fight for survival and see if you’re worth it.’

The film adds to an uneasy viewing experience with switching narrative point of views. Though it does manage to keep tonally consistent, the constant switch up adds to the confusion of a basic question – who is the protagonist? History tells the viewer that the protagonist won’t die. They will be the winner, otherwise, why would the film spend all that time focusing on them? But what happens when it isn’t entirely clear who that person is?

The film adds to an uneasy viewing experience with switching narrative point of views. Though it does manage to keep tonally consistent, the constant switch up adds to the confusion of a basic question – who is the protagonist? History tells the viewer that the protagonist won’t die. They will be the winner, otherwise, why would the film spend all that time focusing on them? But what happens when it isn’t entirely clear who that person is?

The opening of the film gives us a third person look at what is happening before shifting focus to Noriko Nakagawa. Noriko is the audience’s first grounding in the story that we spend the rest of the film invested in. We are given the backstory with their teacher through her eyes and flashbacks and introduced to the other main character, Shuya Nanahara, as the object of Noriko’s teenage crush. But just as we are settling in to feel that this is her story, the film switches again to give us Shuya’s history. We see his life in flashbacks with the addition of voiceover narration. And that’s before we throw in the teacher, Kitano, and the omniscient viewpoint again.

This shifting focus of narrative p.o.v. in this film should not work, and yet it does. It is yet another technique employed by the filmmakers to keep the viewers on their toes, to keep them guessing as to how this story will go.

What’s wrong with killing? Everyone’s got their reasons.

Battle Royale is a brilliant film, but it is not perfect. One particular point of contention for me is around the Battle Royale game/law. The film’s opening sequences of crowds and interested press combined with the expositional text beforehand sets the game up as a very big deal amongst the general public. So why then, when the students wake up within the game, do none of them seem to have any knowledge of the Battle Royale games at all?

We could argue that this is just a clunky way of including exposition about the game – unfortunate but hardly an unforgivable error. But that makes little sense. The students would still need to be walked through exactly how the game worked, showing them the video (that in turn educates the audience) would not necessarily feel unnatural if they were aware of the game. So why make them ignorant? To have them respond to knowing that it was a possibility but never expecting it to happen to them would be far more interesting and would have given us more insight into how the world worked beyond the confines of the game itself.

This is one of those films so dense with philosophy and narrative intrigue there is more than enough to dissect over the course of months of intelligent discussions at the pub. No? You don’t do that with your friends? Perhaps that’s just me then…

Despite a fairly common exposition issue, Battle Royale is an excellent film that will continue to prove popular with viewers for decades to come. If you have never ventured into much Asian cinema, I have nothing but the highest praise to lavish on this film and suggest you try this on for size.

Battle Royale is currently streaming on Netflix.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe