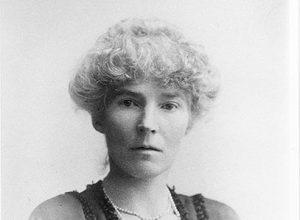

This has been a film I have looked forward to for some time, having seen a segment presented by the director and producer during a conference. This documentary on the life of astounding British traveller, writer, archaeologist and king-maker Gertrude Bell is a very interesting affair in its form alone. Letters from Baghdad recounts the story of the most powerful woman in the British Empire through her own words and those of her contemporaries. Every line in the film is taken from the extensively researched letters of Bell herself, her friends and colleagues, and the major players in the world of Middle Eastern politics in which Bell was so influential. Tilda Swinton’s voiceover as Bell and the performances of other actors reading correspondence in character are played over rare archive footage. We see things as they were in her time, from the Levant all the way to, Bell’s foremost legacy, Iraq.

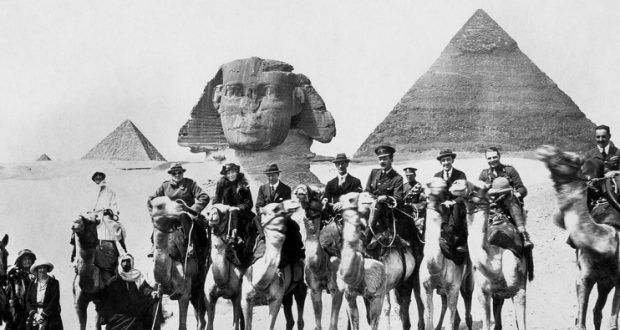

It is very refreshing to see a biographical film of such focus bereft of the vanity and cliché that usually accompanies such endeavours. The story has not be sanded down to fit a neat template. Visually, Bell is hardly in it and instead the visual focus is on the passion of her life: the Middle East. The footage is at once an embellishment – this film could easily have been a radio documentary – but it communicates the world which mesmerised the subject. There are street scenes of bustling tradesmen in Mosul, Baghdad, and Jerusalem. Footage of the digs and excavations of ancient ruins. Domestic scenes of Jewish, Sunni and Shia families. And of course, footage of the British swanning about during their occupation of the territory during and following World War I.

Letters from Baghdad champions cultural dialogue

Directors Zeva Oelbaum and Sabine Krayenbühl have a hard line to walk and manage this by simply surrendering to the complexity of both their subject and her environment. Gertrude herself is not an elusive subject but she was intimately complex, and by all the accounts of her peers, quite difficult due to her rigorous (nay, unachievable) social standards. You’ll be sure to admire Bell for her intelligence, dedication and humanity by the end but this is no hagiography and Letters from Baghdad frames her story very much in the twisted legacy of her works.

Directors Zeva Oelbaum and Sabine Krayenbühl have a hard line to walk and manage this by simply surrendering to the complexity of both their subject and her environment. Gertrude herself is not an elusive subject but she was intimately complex, and by all the accounts of her peers, quite difficult due to her rigorous (nay, unachievable) social standards. You’ll be sure to admire Bell for her intelligence, dedication and humanity by the end but this is no hagiography and Letters from Baghdad frames her story very much in the twisted legacy of her works.

Bell, for those who do not know, was an official of the British government who was renowned as an expert in the matters of the Arabic peoples. Her often brushed-over influence in the wake of World War I saw the creation of a new state, largely defined by her mapping of the region, under a king she chose. That country was Iraq. As messy as pulling apart the fractitious history of the Middle East is, untangling Britain’s Imperial impact is denser, and Bell’s relationship to the Empire denser still.

The British Empire is depicted without nostalgic glory or cartoonish evil. It is as Bell saw it: a mess of contradictions

It’s easy to see that Bell was not engaged in the patronising colonial condescension of her contemporaries: she had a genuine fondness and respect for the numerous ethnic and social units stretching from Turkey through to Mesopotamia. She was, however, ultimately interested in the business of the powerful. Bell was sympathetic to the interests of Arab independence but was working for their chief oppressor. As much as she criticised the roughshod and bungled approach of the British government, she was instrumental in stretching its influence to the point of installing a new monarch on a previously non-existent state. Bell’s ego and follies are as much on display here as her intellect and principles.

It’s easy to see that Bell was not engaged in the patronising colonial condescension of her contemporaries: she had a genuine fondness and respect for the numerous ethnic and social units stretching from Turkey through to Mesopotamia. She was, however, ultimately interested in the business of the powerful. Bell was sympathetic to the interests of Arab independence but was working for their chief oppressor. As much as she criticised the roughshod and bungled approach of the British government, she was instrumental in stretching its influence to the point of installing a new monarch on a previously non-existent state. Bell’s ego and follies are as much on display here as her intellect and principles.

For all the genuine insight into the state of these countries and peoples, and the marvellous footage of life in the region, the figure of Bell (eerily voiced by Swindon) remains the main appeal. She was canny and perceptive, her criticisms and commentary being as relevant today in their observations on the interactions between East and West. What left an impression most strongly by the end of the films was not her recounting of her political manoeuvring or her attempts to safeguard the Arabic cultural identity, but a still image of this forceful and slightly dour woman at play and having fun with a group of German archaeologists whom she had befriended. This film goes beyond an impressive view on a complex segment of world history through the lens of a key figures, it finds moments of intimacy and humanity amongst all the cold dead facts.

Verdict: A stunning film about a stunning figure who should not be forgotten.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe