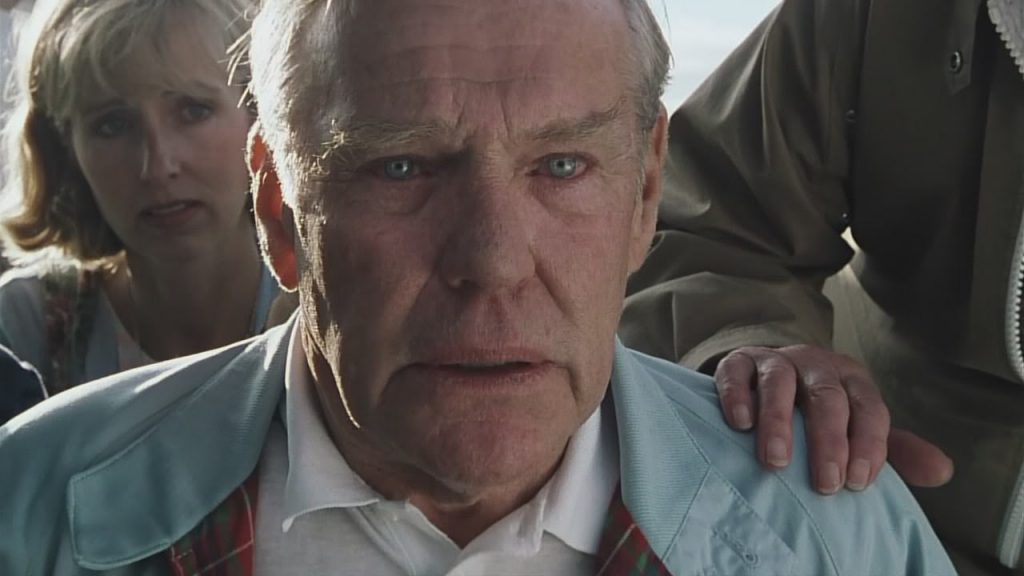

I finally gave in to years of pestering from friends and watched Saving Private Ryan. Perhaps my reputation as a cold, dead fish should have clued them up to the emotional arc falling flat with me, but in my defence, there was one specific reason for the emotional impetus to leave me unaffected: Spielberg’s saccharine bookending of the main narrative. Why did he feel it necessary to clobber the audience over the head with his cloying theme? Did he think his audience was too emotionally stunted to pick up on it without the self-indulgent cemetery set-piece? While this turned into a debate about why the bookending scene was necessary with an increasingly bemused friend, it started me thinking about narrative framing devices in film more generally.

Why are framed narratives so popular? Is it too cynical to think the technique is simply used to occasionally switch up from a standard linear type of storytelling? The frame to a story can do a lot of things – it can provide further context to the story, telling the audience how to view these events; it can suggest that the story is fiction or truth; it can give us exposition dumps efficiently without impacting the pacing of the main narrative; or even draw attention to the artifice of the medium.

Why are framed narratives so popular? Is it too cynical to think the technique is simply used to occasionally switch up from a standard linear type of storytelling? The frame to a story can do a lot of things – it can provide further context to the story, telling the audience how to view these events; it can suggest that the story is fiction or truth; it can give us exposition dumps efficiently without impacting the pacing of the main narrative; or even draw attention to the artifice of the medium.

Entirely fictional films tend to rely on different types of narrative framing than those supposedly ‘based on real events’. These so-called true stories tend to use text at the beginning and end of the film to set-up the narrative context and deliver quick commentary on where those ‘characters’ ended up (similar to Ridley Scott’s Black Hawk Down). These on-screen text pieces are often accompanied by real footage or photographs of the people the story is based on (if available). While this might be considered a cop-out, relying on text to tell the audience information the filmmakers couldn’t get across delicately through the narrative, but I generally don’t mind it as an approach. It is efficient at orienting me as a viewer so the story can get stuck into the action immediately. And when it comes to the text following the close of the narrative – this thoroughly appeals to my nosey nature (of course, that’s only true if I’ve actually enjoyed the film up to that point and care what happened to those people in real life).

So, let’s look into some of the more popular narrative framing devices used in film…

Story within a story

This is probably the most common and most obvious of narrative framing devices, something that even encompasses some of the other more specific types. A story within a story can be characters telling another story within the confines of the narrative or bookend the main narrative as being a story they are telling (Apocalypse Now or Interview with the Vampire – both films based on books with this same device), it could be that they go to a play or experience the telling of a story, it could be flashbacks or dreams. There are any number of variations on this narrative device.

Labelling this kind of framing device as a ‘story within a story’ can be a little misleading. This kind of framing does not require the stories to be truly different from each other. What do I mean by that? Take Saving Private Ryan – this is a story within a story while still having both be part of the same overall narrative. The bookending narrative is that of a soldier visiting the graves of those he served with during the war while the main narrative follows the soldiers who risked their lives to save his. As such, this example is really one and the same story, but the dislocation of time and p.o.v. sets it up as a story within a story.

A film like Stand By Me uses this device in multiple ways. The main narrative is told by a grown-up Gordy, reflecting on events of the past (while also giving us a summary of where they all ended up). But within the main narrative, there is another story being told that is already framed. Confused? It might seem convoluted when looked at this way, but it actually works very well. Gordy always wanted to be a writer, inventing stories and letting his imagination run wild. Around the campfire, Gordy tells the boys a tale to take their minds off their grisly mission, which is played out as a plot in its own right on-screen.

A film like Stand By Me uses this device in multiple ways. The main narrative is told by a grown-up Gordy, reflecting on events of the past (while also giving us a summary of where they all ended up). But within the main narrative, there is another story being told that is already framed. Confused? It might seem convoluted when looked at this way, but it actually works very well. Gordy always wanted to be a writer, inventing stories and letting his imagination run wild. Around the campfire, Gordy tells the boys a tale to take their minds off their grisly mission, which is played out as a plot in its own right on-screen.

Beginning at the end

There is an intense situation and the viewer is dropped into it without context. Boom. But don’t worry, the story will rewind imminently and take you on a journey that will end where it began (or at least around about then, usually working out the final conclusion shortly after the story re-joins the opening gambit). This kind of framing has been around for a long time, from classic films like All About Eve, Sunset Boulevard, and Double Indemnity to modern classics like Fight Club, Lantana, Pulp Fiction, American Beauty, and Inception. Then, of course, there’s Memento – a further twist on this set-up.

There is an intense situation and the viewer is dropped into it without context. Boom. But don’t worry, the story will rewind imminently and take you on a journey that will end where it began (or at least around about then, usually working out the final conclusion shortly after the story re-joins the opening gambit). This kind of framing has been around for a long time, from classic films like All About Eve, Sunset Boulevard, and Double Indemnity to modern classics like Fight Club, Lantana, Pulp Fiction, American Beauty, and Inception. Then, of course, there’s Memento – a further twist on this set-up.

This kind of device is a double-edged sword for the filmmakers. While it can immediately bring enormous tension to a story it potentially also gives the game away. Instead of the audience asking ‘what will happen’ it is all about ‘how’. So the onus is on creating an interesting journey full of other tensions. This is why it can be a particularly rewarding story style if done well – there are necessarily multiple tensions running through the narrative, some you know the outcomes of, others you don’t.

Let me read you a story…

Stories are escapes into other worlds. Some films like to take this idea quite literally. This device is a common technique used in classic Disney films (such as Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Robin Hood…), which is often represented with an actual storybook on-screen – before the action begins, we are given a fairytale-style opening and at the end, we see ‘The End’ written on the page, before the book is closed. While this does tend to be a more common technique in children’s films, it also pops up in comedy from time to time. Two classic live-action examples of this are The Princess Bride and The NeverEnding Story. Both have central narratives that are books comes to life.

Stories are escapes into other worlds. Some films like to take this idea quite literally. This device is a common technique used in classic Disney films (such as Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Robin Hood…), which is often represented with an actual storybook on-screen – before the action begins, we are given a fairytale-style opening and at the end, we see ‘The End’ written on the page, before the book is closed. While this does tend to be a more common technique in children’s films, it also pops up in comedy from time to time. Two classic live-action examples of this are The Princess Bride and The NeverEnding Story. Both have central narratives that are books comes to life.

It doesn’t always need to be quite so clear cut though. Take The Notebook as an example. This has elements of ‘story within a story’ as well as being a ‘storybook’ framed narrative. A further twist on the device used in the film is that the story is being read by one of the protagonists of the main narrative, reading it as written by the other protagonist. It is both a story dislocated in time as well as being a kind of flashback and the bringing to life of a story read by the characters on-screen.

I may not be telling you the truth

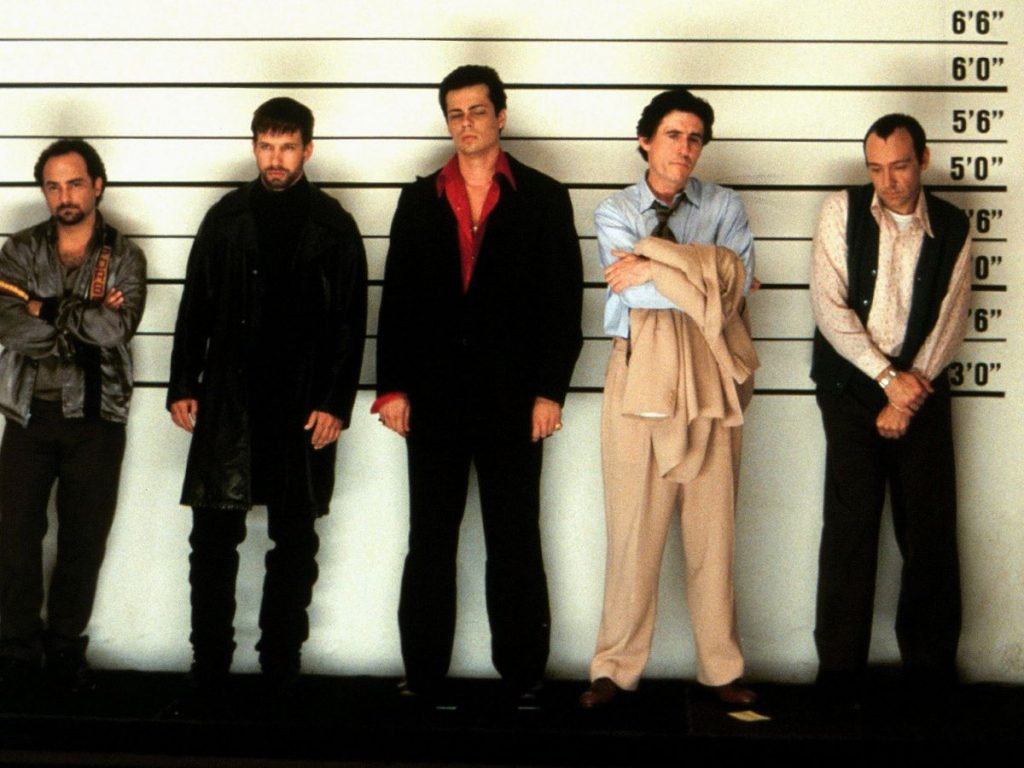

Unreliable narrators often go hand in hand with framed narrative films. It is difficult to get away with an unreliable narrator without alienating the audience – we tend to watch films in a way that makes us trust what we are seeing, assuming it is being presented as accurate (in terms of the fictional world). But framing the story as being narrated by someone with a particular agenda or perspective helps to mitigate the potential fallout of revealing that the narrative was not accurate and that the audience has been lied to all along. Perhaps the most well-known film that uses this narrative device is The Usual Suspects, though Fight Club is high up on that list as well.

Unreliable narrators often go hand in hand with framed narrative films. It is difficult to get away with an unreliable narrator without alienating the audience – we tend to watch films in a way that makes us trust what we are seeing, assuming it is being presented as accurate (in terms of the fictional world). But framing the story as being narrated by someone with a particular agenda or perspective helps to mitigate the potential fallout of revealing that the narrative was not accurate and that the audience has been lied to all along. Perhaps the most well-known film that uses this narrative device is The Usual Suspects, though Fight Club is high up on that list as well.

Again, Memento plays with this idea. Instead of being a wilfully unreliable narrator (which is usually how unreliable narrators play out), he is unable to provide an accurate recollection of events. The viewer is left to piece the truth together, much as Lenny does. Similarly in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, having deliberately played with their memories, every recollection is called into question. Tim Burton’s Big Fish is another unusual example, where the unreliable aspect is part of the character’s charm – the story of a man who embellishes his ordinary life with fantastical stories in order to find wonder in the ordinary.

When done well, narrative framing devices draw the viewer in and allow the filmmakers to manipulate their audience. They add interesting complexity to the structure of storytelling, providing multiple perspectives on events and playing with the trust of the audience. As long as the framing device is used to add to the narrative rather than batter us with emotional rhetoric (Spielberg!), they prove interesting and memorable elements in a lot of classic films.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe