With a new latter-day sequel trudging across cinema screens, we are provided with a great opportunity to review the iconic cyberpunk noir masterpiece Blade Runner. Established now with a pristine reputation, the film was initially released to critical derision and a ghastly performance at the box office. Director Ridley Scott, who has never admitted fault ever, stood by the film despite all the interference it had at release. The simple tale of a cop hunting down artificial humans in the ruins of LA has nonetheless rehabilitated itself with time. These days, uttering a dislike of the film is grounds for a summary execution in cinephile circles. But for the first-time viewer, there is one major question to be answered: which version should you watch?

There are nominally 6 different cuts of Blade Runner, each produced off the back of successive waves of studio interference and attempts to realise it as the creators intended. In terms of actual interest, three can be dismissed fairly promptly: the working cut, the more violent international cut, and the edited-for-TV cut. Besides some brief unique shots in the working cut, these don’t deviate substantially from the original theatrical release and the extra material is available in the later director’s versions. The three iconic versions are then the Domestic Cut, the Director’s Cut, and the Final Cut.

This was an especially iterative example of art being born of adversity

Of the three, the Domestic Cut is generally considered the weakest, though it has fans who will defend it tooth and nail from the revisionists. It was this version that inspired the savaging of film critics internationally and which drove customers away from movie theatres. The main points of contention rest on two factors: the voiceover and the ‘happy ending’. Fearing that this slow and reflective thriller would baffle audiences, the studio insisted that main star Harrison Ford provide a voiceover from protagonist Deckard’s perspective. Of course, being a noir thriller, this is hardly the most inappropriate direction to take. The grizzled gumshoe narrating his investigation is a staple of the genre and the loyalists very much view it in this light. The issues come with Ford’s delivery – some suspect he purposefully performed badly to scupper this feature, though he denies this – and the crass redundancy of the writing. The script meanders around with empty reflections and, at best, repeats information that can be gleaned from the film visually. As you can tell, I am not overly enamoured of this.

Of the three, the Domestic Cut is generally considered the weakest, though it has fans who will defend it tooth and nail from the revisionists. It was this version that inspired the savaging of film critics internationally and which drove customers away from movie theatres. The main points of contention rest on two factors: the voiceover and the ‘happy ending’. Fearing that this slow and reflective thriller would baffle audiences, the studio insisted that main star Harrison Ford provide a voiceover from protagonist Deckard’s perspective. Of course, being a noir thriller, this is hardly the most inappropriate direction to take. The grizzled gumshoe narrating his investigation is a staple of the genre and the loyalists very much view it in this light. The issues come with Ford’s delivery – some suspect he purposefully performed badly to scupper this feature, though he denies this – and the crass redundancy of the writing. The script meanders around with empty reflections and, at best, repeats information that can be gleaned from the film visually. As you can tell, I am not overly enamoured of this.

The ‘happy ending’ is the far more ridiculous of the studio-enforced changes though. Afraid that the ambiguous ending would deter audiences, the studio inserted brief sequences at the finale of Deckard and his lover Rachel fleeing the murky streets of LA to emerge into the resplendent sunlight of the countryside. Somewhat misjudged for a thoughtful noir story. The footage of the rolling hills beyond the boundaries of Los Angeles wasn’t even shot for the film: it’s unused footage of the hills that compose the opening of The Shining. The schmaltzy delivery of the characters from any of the darkness or uncertainty that mires the film’s world is an inappropriate and cack-handed feature.

The ending of the Original Cut makes it feel like the Disney version of Blade Runner

The erroneously titled Director’s Cut, by comparison, is the major transition between the studio version and what some consider the definitive version helmed by Scott. Released 10 years after the original, it was not in fact recut by the director himself but by film restorer Michael Arick, who did a rough cut with Scott’s notes which he refined after working with the director himself. Gone were the voiceovers and the happy ending. Inserted were additional lines from the enigmatic character Gaff and, more bizarrely, a unicorn dream sequence. Both contribute to arguably the biggest artistic departure from the themes of the original cut. Though all versions question the nature of existence and identity, with the simulacra humans seeking out a way to realise a full human lifespan, the director’s cut introduced the idea that Deckard was himself a replicant.

The erroneously titled Director’s Cut, by comparison, is the major transition between the studio version and what some consider the definitive version helmed by Scott. Released 10 years after the original, it was not in fact recut by the director himself but by film restorer Michael Arick, who did a rough cut with Scott’s notes which he refined after working with the director himself. Gone were the voiceovers and the happy ending. Inserted were additional lines from the enigmatic character Gaff and, more bizarrely, a unicorn dream sequence. Both contribute to arguably the biggest artistic departure from the themes of the original cut. Though all versions question the nature of existence and identity, with the simulacra humans seeking out a way to realise a full human lifespan, the director’s cut introduced the idea that Deckard was himself a replicant.

This is still contentious for some, who think the change does not integrate well into the film. Certainly, it is another deviation from the source material: Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep. Typical of Dick’s work, he was a drug-taking schizophrenic after all, the characters face various existential crises as they struggle to confront notions of what is or is not real. Excised from the film are plot threads concerning animal ownership as a status symbol with an industry of robotic replacements built around it, religions based on collective martyrdom experiences, and machines that can artificially induce emotions. Crucially, what is not questioned (beyond an elaborate bluff in the middle of the book) is whether or not Deckard is himself a replicant.

The conceit that people are not really people but false simulacra is key in Dick’s fiction

As a Philip K Dick enthusiast, I personally have no issues with the deviations. The film does a good job of adapting so many other aspects of the work – especially the rather stunted emotional range of the characters and their existential disinterest, so typical of Dick’s books – and more than carves out an identity of its own. Similarly, I think the change to make Deckard the subject of his own existential crisis works very well within the film and heightens the contrast between him and sympathetic antagonist Roy, the charismatic leader of the replicants. Nonetheless, some see the change as aberrant and not in keeping with the film’s narrative: that it is and should be about a real human confronted with the morality of ‘retiring’ replicants and coming to find value in their brief lives. They maintain that Scott, much like George Lucas and the Star Wars prequels, does not fundamentally understand the original material he worked on.

25 years after Blade Runner first hit screens in 1982, we received what Scott calls his definitive version of the film: the Final Cut. The footage was painstakingly restored from the original negatives and the mesmerising soundtrack by Vangelis enhanced to meet modern audio standards. In keeping with Scott’s take on the film, the unicorn stayed (in fact this version has the ‘full version’ of the dream intercut with Deckard), some of the more oblique insinuations of Deckard’s nature by Gaff were removed, the more violent scenes and alternate edits from the international version were added as well. Perhaps not substantially different from the 1992 Director’s Cut, it is the version most will now defer to and offers the best picture quality on screen.

25 years after Blade Runner first hit screens in 1982, we received what Scott calls his definitive version of the film: the Final Cut. The footage was painstakingly restored from the original negatives and the mesmerising soundtrack by Vangelis enhanced to meet modern audio standards. In keeping with Scott’s take on the film, the unicorn stayed (in fact this version has the ‘full version’ of the dream intercut with Deckard), some of the more oblique insinuations of Deckard’s nature by Gaff were removed, the more violent scenes and alternate edits from the international version were added as well. Perhaps not substantially different from the 1992 Director’s Cut, it is the version most will now defer to and offers the best picture quality on screen.

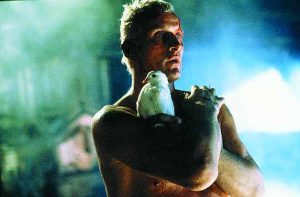

That is indeed the version I first saw and one I fell in love with. Blade Runner makes no apologies for the challenges it poses. It is slow, the simple plot is by no means told in the most simple fashion, and many of the characters are closed books who are determined not to reveal their true vulnerable nature. Glimpsed through the cigarette smoke that pervades every room, the dilapidated remnants of Los Angeles show us not a future of hope, but a bleak one that is old before its time. And yet for all its miserable milieu, there are people here – the fugitive replicants, striving to live just a little bit longer. Trying to experience just one more day eked out in the rainy and grimy metropolis. All the while Deckard, a Blade Runner brought reluctantly back into service, has to morosely do his job and ‘retire’ them all…

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe