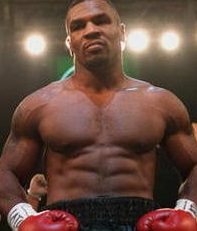

Mike Tyson. Iron Mike. The baddest man on the planet. Five foot ten of unstoppable, unfettered carnage. A disciplined machine of purpose and destruction. Effectively orphaned at 16, Tyson took up boxing in juvenile detention, falling under the wing of paternal boxing coach Cus D’Amato. He became the heavyweight champion of the world at twenty. Twelve of his first nineteen professional bouts were won by first round knockout, and so it continued. The fight that gave Tyson all three heavyweight titles (WBC, WBA, IBF) lasted 91 seconds. These were fights earning Tyson tens of millions of dollars, the subject of months of build-up, and his only focus was to get the job done. He could do it before some of the audience had even found their seats.

Mike Tyson. Iron Mike. The baddest man on the planet. Five foot ten of unstoppable, unfettered carnage. A disciplined machine of purpose and destruction. Effectively orphaned at 16, Tyson took up boxing in juvenile detention, falling under the wing of paternal boxing coach Cus D’Amato. He became the heavyweight champion of the world at twenty. Twelve of his first nineteen professional bouts were won by first round knockout, and so it continued. The fight that gave Tyson all three heavyweight titles (WBC, WBA, IBF) lasted 91 seconds. These were fights earning Tyson tens of millions of dollars, the subject of months of build-up, and his only focus was to get the job done. He could do it before some of the audience had even found their seats.

There were complexities to Tyson too. His focus on discipline but willingness to play the ‘savage’; his extreme sexual tastes and use of prostitutes; the tears shed at D’Amato’s passing. There was his conversion to Islam while serving three years for rape; his large prison tattoos of Mao and Guevara; his lifelong hobby of pigeon-fancying. He earned hundreds of millions of dollars boxing, and declared bankruptcy in 2003. He originally intended his Maori face tattoo to be love hearts. No matter how great his achievements, wealth and fame, deep down the fat, sensitive prepubescent stick-up artist from Brooklyn remained, a nagging and fearful insecurity.

There were complexities to Tyson too. His focus on discipline but willingness to play the ‘savage’; his extreme sexual tastes and use of prostitutes; the tears shed at D’Amato’s passing. There was his conversion to Islam while serving three years for rape; his large prison tattoos of Mao and Guevara; his lifelong hobby of pigeon-fancying. He earned hundreds of millions of dollars boxing, and declared bankruptcy in 2003. He originally intended his Maori face tattoo to be love hearts. No matter how great his achievements, wealth and fame, deep down the fat, sensitive prepubescent stick-up artist from Brooklyn remained, a nagging and fearful insecurity.

Stars used to be godlike figures, a contemporary mythology. The glamour and mystique of postwar Hollywood’s famous faces suggested life on another plane, a larger scale, into which everyday joes could only steal a peeked glimpse. Through turbulent personal lives, they spoke with authority, the scale of their complexities and achievements offering a look at a world ordinary folks simply wouldn’t understand. Nowadays though, we understand all too well. The galaxy of stars has been dimmed, by the light of the information age, to mere ‘celebs’; the familiarity and mundanity of easy, constant access lets us follow every paid appearance and petty endorsement of those famous for being famous. Mike Tyson was one of the last great stars, but now he’s been brought down to earth, seemingly ‘on the verge of dying’ from his addictions. But he may not be the last.

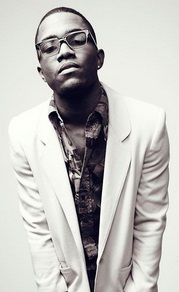

Angel Haze. Bars for days.

Angel Haze. A name sounding like very good drugs and a backstory PRs would kill for. Of mixed Native American and African American heritage, Haze was raised in a Pentecostal ‘cult’ (her word), forbidding her from hearing any secular music until she was 14. Haze built her standing through the modern model of issuing free download releases (in place of street mixtapes) ahead of her proper album release, Dirty Gold, due later this year. With a range from the romantic longing of ‘Gypsy Letters‘ to the possession nightmare ‘Wicked Moon‘, the Reservation EP gave Haze her choice of deal. The flipside to the information age’s ease of access, an artist can prove themselves before even releasing an album.

Angel Haze. A name sounding like very good drugs and a backstory PRs would kill for. Of mixed Native American and African American heritage, Haze was raised in a Pentecostal ‘cult’ (her word), forbidding her from hearing any secular music until she was 14. Haze built her standing through the modern model of issuing free download releases (in place of street mixtapes) ahead of her proper album release, Dirty Gold, due later this year. With a range from the romantic longing of ‘Gypsy Letters‘ to the possession nightmare ‘Wicked Moon‘, the Reservation EP gave Haze her choice of deal. The flipside to the information age’s ease of access, an artist can prove themselves before even releasing an album.

A Dr. King speech in the mouth of a freak.

Much as linguistics still uses gender to classify nouns, hip hop remains heavily codified with ideas of masculine and feminine. Sociological theories are plentiful. In a deprived environment, masculinity has greater value as a way of asserting your standing among others; a shorthand for strength and integrity. As many elements of hip hop fashion (baggy clothing, jumpsuits, unlaced trainers) have been brought back from prison, so has the notion of the prison bitch. As Ice-T observed in that manual of gangsta rap, his 1991 classic OG: Original Gangster, ‘some of y’all niggas is bitches too’. The misogynistic use of ‘bitch’ remains rife, but it isn’t necessarily gender-specific, femininity being broadly equated with weakness. Even Slaughterhouse’s Joe Budden, an artist capable of tracks as thunderous as the Tyson-namechecking ‘Inception’, has been repeatedly labelled an ‘emo rapper’ for daring to air vulnerability on record (one of his mottos being ‘music is what feelings sound like’).

Much as linguistics still uses gender to classify nouns, hip hop remains heavily codified with ideas of masculine and feminine. Sociological theories are plentiful. In a deprived environment, masculinity has greater value as a way of asserting your standing among others; a shorthand for strength and integrity. As many elements of hip hop fashion (baggy clothing, jumpsuits, unlaced trainers) have been brought back from prison, so has the notion of the prison bitch. As Ice-T observed in that manual of gangsta rap, his 1991 classic OG: Original Gangster, ‘some of y’all niggas is bitches too’. The misogynistic use of ‘bitch’ remains rife, but it isn’t necessarily gender-specific, femininity being broadly equated with weakness. Even Slaughterhouse’s Joe Budden, an artist capable of tracks as thunderous as the Tyson-namechecking ‘Inception’, has been repeatedly labelled an ‘emo rapper’ for daring to air vulnerability on record (one of his mottos being ‘music is what feelings sound like’).

This emphasis on gender coding’s led to the ludicrous trend of qualifying any remotely flattering statement between men with ‘no homo’ – as if anyone was asking – and the issue’s further complicated by hip hop’s typical ‘bad meaning good’ reclamation of ‘bitch’, as tough women to be reckoned with. There have been recent exceptions: up and coming A$AP Rocky stated that hip hop needs to ‘stop being so close-minded’ about homosexuality (only for his own sexuality to become the subject of speculation) and Odd Future, often criticized for their use of homophobic language, were found to have not one but two gay members when vocalist Frank Ocean came out. Rather than a rapper though, Frank is primarily a singer.

This emphasis on gender coding’s led to the ludicrous trend of qualifying any remotely flattering statement between men with ‘no homo’ – as if anyone was asking – and the issue’s further complicated by hip hop’s typical ‘bad meaning good’ reclamation of ‘bitch’, as tough women to be reckoned with. There have been recent exceptions: up and coming A$AP Rocky stated that hip hop needs to ‘stop being so close-minded’ about homosexuality (only for his own sexuality to become the subject of speculation) and Odd Future, often criticized for their use of homophobic language, were found to have not one but two gay members when vocalist Frank Ocean came out. Rather than a rapper though, Frank is primarily a singer.

There’s an expectation that female rappers will also be singers. Rap is primarily confident, competitive bragging; r&b singing’s traditionally dealt with more vulnerable emotions. So a precedent exists, but a feminine one. Female rappers are expected to be sexy; while male homosexuality is taken as a weakness, female bisexuality (such as that of Nicki Minaj) is effectively encouraged, as empowering under rap’s gender rules.

My tongue is the fucking rapture, bitch.

Angel Haze can sing, but she is ‘sure as hell not’ bisexual. Haze describes herself as pansexual, and released a track stating as much (in her remix of Macklemore’s ‘Same Love’) on virtually the same day as Morrissey released a similar statement, in the wake of his Autobiography, that he is ‘humasexual’. (And if you think the comparison’s unlikely, compare Angel’s ‘Stay draped in black ‘cause it matches my soul’, from her ‘Black Skinhead’ freestyle, with Moz’s Smiths line, ‘I wear black on the outside/’Cause black is how I feel on the inside’.)

Angel Haze can sing, but she is ‘sure as hell not’ bisexual. Haze describes herself as pansexual, and released a track stating as much (in her remix of Macklemore’s ‘Same Love’) on virtually the same day as Morrissey released a similar statement, in the wake of his Autobiography, that he is ‘humasexual’. (And if you think the comparison’s unlikely, compare Angel’s ‘Stay draped in black ‘cause it matches my soul’, from her ‘Black Skinhead’ freestyle, with Moz’s Smiths line, ‘I wear black on the outside/’Cause black is how I feel on the inside’.)

‘Same Love’ is part of Haze’s current #30Gold project, to drop 30 new beatjack/cover tracks in the run up to Dirty Gold’s release. The greatness of Haze can be summed up by #30Gold’s tracks 6 to 8. Macklemore’s ‘Same Love’ is a straight man’s voicing of support for gay rights, and interviewed for Noisey – dressed as Annie Hall reimagined as a tropical gun runner – Haze eloquently questions how much (or little) difference its success will actually make. Her own version is a beautiful, incendiary and fearlessly personal rebuking of homophobia, and a refusal of the labelling of sexuality. In contrast, Haze followed it with a raw rendition of Miley Cyrus’s ‘Wrecking Ball’, accompanied only by an acoustic guitar and showing the full force of her singing voice. Track 8, in contrast again, revisited Haze’s own ‘New York’ for a brutal shredding of any rap opposition (‘You will run, you will cry, you will need your mama, bitch!’).

‘Werkin Girls’, with the ironic disinterest of its ‘tundra’ verse and its Kruger-clawed, Lynchian masterpiece trip of a video, showed (much like Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s mesmerizing So Many Ways To Sleep Badly or Bret Easton Ellis’s spat with GLAAD earlier this year) that those thought to be the subject of it can be equally frustrated by the preciousness of political correctness. Lupe Fiasco stands as one of the last bastions on conscious hip hop viable in the mainstream, and while he tried to unpick hip hop’s gender issues on ‘Bitch Bad’, from his underrated Food & Liquor II, Angel felt ‘I had to embarrass Lupe Fiasco because he did it all wrong. He did the woman-shaming, ‘It’s your fault, bitch’ thing. The feminist in me wouldn’t let this live. For me, it was important to portray what he couldn’t.’ Haze’s own version is a similar narrative cycle of negative gender attitudes, but crucially with greater gender balance. The most devastating entry in Haze’s canon so far though is her rendition of Eminem’s ‘Cleaning Out My Closet’. Much as Em’s original trawled the personal issues of his past for closure, Haze uses the track to revisit the sexual abuse she suffered between the ages of 7 and 10. The result is an unflinching, excruciating reclamation of her own narrative and the clearest example of her trademark approach, converting pain into determination and authority. As she notes on ‘This Is Me’: ‘And if it’s pain that you were feeling, you release it till it stops/Or else it’ll get stronger and just beat you till you drop’. Haze is strong enough not just to show weakness, but to grow stronger from it.

‘Werkin Girls’, with the ironic disinterest of its ‘tundra’ verse and its Kruger-clawed, Lynchian masterpiece trip of a video, showed (much like Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s mesmerizing So Many Ways To Sleep Badly or Bret Easton Ellis’s spat with GLAAD earlier this year) that those thought to be the subject of it can be equally frustrated by the preciousness of political correctness. Lupe Fiasco stands as one of the last bastions on conscious hip hop viable in the mainstream, and while he tried to unpick hip hop’s gender issues on ‘Bitch Bad’, from his underrated Food & Liquor II, Angel felt ‘I had to embarrass Lupe Fiasco because he did it all wrong. He did the woman-shaming, ‘It’s your fault, bitch’ thing. The feminist in me wouldn’t let this live. For me, it was important to portray what he couldn’t.’ Haze’s own version is a similar narrative cycle of negative gender attitudes, but crucially with greater gender balance. The most devastating entry in Haze’s canon so far though is her rendition of Eminem’s ‘Cleaning Out My Closet’. Much as Em’s original trawled the personal issues of his past for closure, Haze uses the track to revisit the sexual abuse she suffered between the ages of 7 and 10. The result is an unflinching, excruciating reclamation of her own narrative and the clearest example of her trademark approach, converting pain into determination and authority. As she notes on ‘This Is Me’: ‘And if it’s pain that you were feeling, you release it till it stops/Or else it’ll get stronger and just beat you till you drop’. Haze is strong enough not just to show weakness, but to grow stronger from it.

In addition to unflinching lyricism and unstoppable flow, Haze – currently 22 – wields dextrous double-time skills and battle raps that dispatch legions of bitches. Like Odd Future, she adopts predominant attitudes to money, hoes and giving no fucks but subverts the clichés, as in the videos for Dirty Gold’s ‘No Bueno’ and ‘Echelon’. As #30Gold continues to gain headlines and build a dedicated fanbase, it’s opened to submissions of beats from fans. When #30Gold reaches completion and Dirty Gold finally drops, a star will have arrived. The world will just have to work out how to deal with it.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe