“Always [she] explores relentlessly the eternal themes that obsess her: love, loss, madness, the nature of the father– daughter compact, and death – the Death Baby we carry with us from the moment of birth”

Then US poet laureate Maxine Kumin wrote those words about her friend and fellow poet Anne Sexton in 1981, seven years after Sexton’s suicide. She could easily have been writing about Lana Del Rey. Two albums and an EP in from her arrival with Born to Die, Del Rey has already built a world. There’s a point in a heavy night’s drinking when, having travailed the tumult and chaos of the night, you in the wee small hours reach the calms of the other side; a quiet moment of reflection and bravado. This is where the music of Del Rey lives.

Then US poet laureate Maxine Kumin wrote those words about her friend and fellow poet Anne Sexton in 1981, seven years after Sexton’s suicide. She could easily have been writing about Lana Del Rey. Two albums and an EP in from her arrival with Born to Die, Del Rey has already built a world. There’s a point in a heavy night’s drinking when, having travailed the tumult and chaos of the night, you in the wee small hours reach the calms of the other side; a quiet moment of reflection and bravado. This is where the music of Del Rey lives.

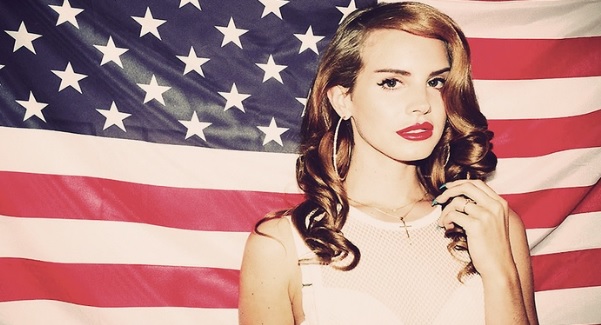

Lanaland is an LA noir landscape populated with sharply drawn, Carveresque relationships and American archetypes. Barflies and biker gangs; gang members and fading starlets; couples plotting smalltown escape and blue jeans, white shirt James Deans. It’s American through and through, but ironized and ambiguous– its creator falls “asleep in the American flag”. It evokes the same workaday atmosphere as Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Nebraska’ (itself drawn from Terrence Malick’s Badlands), with the same undercurrents of crime and sexual danger. Its kitsch Americana reaches its apotheosis in Del Rey’s three-act short film Tropico – a dreamlike journey through the American night, interleaved with poetry by Whitman, Ginsberg and John Mitchum. “Body Electric”’s claim that “Elvis is my daddy, Marilyn’s my mother, Jesus is my bestest friend” creates a Garden of Eden in which John Wayne is God to Lana’s Eve and Virgin Mary, before the fall turns the world into strippers and tattooed Latino gang members.

Lanaland is an LA noir landscape populated with sharply drawn, Carveresque relationships and American archetypes. Barflies and biker gangs; gang members and fading starlets; couples plotting smalltown escape and blue jeans, white shirt James Deans. It’s American through and through, but ironized and ambiguous– its creator falls “asleep in the American flag”. It evokes the same workaday atmosphere as Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Nebraska’ (itself drawn from Terrence Malick’s Badlands), with the same undercurrents of crime and sexual danger. Its kitsch Americana reaches its apotheosis in Del Rey’s three-act short film Tropico – a dreamlike journey through the American night, interleaved with poetry by Whitman, Ginsberg and John Mitchum. “Body Electric”’s claim that “Elvis is my daddy, Marilyn’s my mother, Jesus is my bestest friend” creates a Garden of Eden in which John Wayne is God to Lana’s Eve and Virgin Mary, before the fall turns the world into strippers and tattooed Latino gang members.

The music of this world is swooning, string-laden bombast, charged with all the melodrama of Mexican telenovelas. Del Rey does not do fast songs. Her distinctive deadpan delivery, hanging behind the beat, is as level delivering lines like “I’m churning out novels like beat poetry on amphetamines” as “My pussy tastes like Pepsi Cola”. Rarely has the word “ultraviolence” been sung with such calm, dead-eyed recognition. Everything about ‘Is This Happiness’ – a song about a couple trying to hold their relationship together while writing in Hollywood – answers its title with an emphatic no. The only flat-out upbeat song in the Del Rey songbook is a bizarrely tropical ode to smuggling cocaine in Florida.

The music of this world is swooning, string-laden bombast, charged with all the melodrama of Mexican telenovelas. Del Rey does not do fast songs. Her distinctive deadpan delivery, hanging behind the beat, is as level delivering lines like “I’m churning out novels like beat poetry on amphetamines” as “My pussy tastes like Pepsi Cola”. Rarely has the word “ultraviolence” been sung with such calm, dead-eyed recognition. Everything about ‘Is This Happiness’ – a song about a couple trying to hold their relationship together while writing in Hollywood – answers its title with an emphatic no. The only flat-out upbeat song in the Del Rey songbook is a bizarrely tropical ode to smuggling cocaine in Florida.

While Del Rey songs are sung in the first person, the protagonists vary enough to clearly be separate. Their similarities and overlap in actions and motivation though, invite biographical reading. Lines are blurred further by Del Rey’s efforts in interviews to offer a backstory as fantastical as Dylan in his press-manipulating heyday.

While Del Rey songs are sung in the first person, the protagonists vary enough to clearly be separate. Their similarities and overlap in actions and motivation though, invite biographical reading. Lines are blurred further by Del Rey’s efforts in interviews to offer a backstory as fantastical as Dylan in his press-manipulating heyday.

You’ve got your gun, I’ve got my dad

Father figures are ubiquitous in Lanaland. In a world where God is absent (“Me and God don’t get along”) or dead, the father is a God-like figure who’s gone on ahead, trailing wisdom and high expectations. An iconic figure of love to pledge allegiance to; who’s lived life to success and “made his life an art”. Mothers, in contrast, are virtually absent, while love interests are candidates to be a new “full-time daddy”.

If I get a little prettier, can I be your baby?

Men in Del Rey songs are invariably older, flawed but brilliant. They’re occupied by drinking and cocaine, motorbikes and tattoos; attracted to the “bad girls” that are “crazy” (but we’ll get to that). Women are fragile, seductive and desperate for love. The songs are strewn with the accoutrements of femininity: nail polish, lipstick, perfume; bikinis, big beauty queen hair and the recurring little red party dress – which Alex Petridis noted “Del Rey [puts] on or [takes] off with the frequency of a woman having a crisis in the changing rooms at TK Maxx”. And it’s not just the getting (un)dressed, but the being watched doing so.

Men in Del Rey songs are invariably older, flawed but brilliant. They’re occupied by drinking and cocaine, motorbikes and tattoos; attracted to the “bad girls” that are “crazy” (but we’ll get to that). Women are fragile, seductive and desperate for love. The songs are strewn with the accoutrements of femininity: nail polish, lipstick, perfume; bikinis, big beauty queen hair and the recurring little red party dress – which Alex Petridis noted “Del Rey [puts] on or [takes] off with the frequency of a woman having a crisis in the changing rooms at TK Maxx”. And it’s not just the getting (un)dressed, but the being watched doing so.

Del Rey’s most striking summation of womanhood is the “freshman generation of degenerate beauty queens” with “mascara running down [their] little Bambi eyes” in ‘This Is What Makes Us Girls’. A quintessential quality of sisterhood? “We don’t stick together ‘cause we put love first.” Kim Gordon (whose own songs had long been the high points of Sonic Youth records) wrote in her Girl in a Band autobiography, “Today we have someone like Lana Del Rey … who believes women can do whatever they want, which, in her world, tilts toward self-destruction, whether it’s sleeping with gross old men or being a transient biker queen.”

Del Rey’s women may just want to be loved and looked after like children, but their femininity is a performance. Lines like “I can be a china doll, if you want to see me fall” are all too aware of the powerful attraction their weakness wields. While they may be told to “Be a good baby and do what I want”, they exert a control through submission. “This Is What Makes Us Girls” yells “Get us while we’re hot”, but follows it immediately with a dare of “Come on and take a shot.” This isn’t coy but deliberate and direct, the overtly put-on little-girl voices of “Off to the Races” making the manipulation clear (and stronger for its blatancy). “I was an angel” she proclaims, “Looking to get fucked hard”. This is obsession and cold, hard seduction. The distancing of Del Rey’s delivery doesn’t make a case, just puts these lines before you like, Is it not so? Would you say no? Almost heroically dislikable in its honesty.

Del Rey’s women may just want to be loved and looked after like children, but their femininity is a performance. Lines like “I can be a china doll, if you want to see me fall” are all too aware of the powerful attraction their weakness wields. While they may be told to “Be a good baby and do what I want”, they exert a control through submission. “This Is What Makes Us Girls” yells “Get us while we’re hot”, but follows it immediately with a dare of “Come on and take a shot.” This isn’t coy but deliberate and direct, the overtly put-on little-girl voices of “Off to the Races” making the manipulation clear (and stronger for its blatancy). “I was an angel” she proclaims, “Looking to get fucked hard”. This is obsession and cold, hard seduction. The distancing of Del Rey’s delivery doesn’t make a case, just puts these lines before you like, Is it not so? Would you say no? Almost heroically dislikable in its honesty.

I’m fucking crazy

“Crazy” may be the most frequent word in Del Rey’s vocabulary. LDR’s women are bad girls and bad bitches, crazy messes and ride-or-dies, with Las Vegas pasts, crass LA manners and tar-black souls. But why so crazy?

Absent fathers and invisible mothers; God fled; decadence worn to the hollow, threadbare euphemisms of Friday nights, “party” and those who like to “have some fun”. Even success is meaningless, as “Old Money”’s sorrowful litany of luxury states. Ultraviolence, Del Rey’s second album, portrays success like a rainy Sunday afternoon, to be wearily dismissed. So what’s left to pray for, what Heaven left to hope?

Absent fathers and invisible mothers; God fled; decadence worn to the hollow, threadbare euphemisms of Friday nights, “party” and those who like to “have some fun”. Even success is meaningless, as “Old Money”’s sorrowful litany of luxury states. Ultraviolence, Del Rey’s second album, portrays success like a rainy Sunday afternoon, to be wearily dismissed. So what’s left to pray for, what Heaven left to hope?

Del Rey’s music looks to love as the most important thing, the solution for everything. Not because that’s likely but because it’s the only viable option left for “lost” people to get found. Not a victory march but a broken hallelujah. It’s a desperation Sexton would recognise:

Today is made of yesterday, each time I steal

toward rites I do not know, waiting for the lost

ingredient, as if salt or money or even lust

would keep us calm and prove us whole at last

This isn’t the starry-eyed excitement of first love. Del Rey sings with the air of someone who’s been there, done that, and found there wasn’t much to see. The awareness that it’s such a long shot is where the tragedy lies. An awareness that however self-destructive your behaviour, it’s still your best chance at satisfaction. Del Rey’s women may be uncertain of themselves but they’re striving for salvation. And in such high stakes, only total devotion like “You’re my cult leader, I love you forever” will do. LDR’s heroines aren’t “crazy” for not knowing what they’re doing; they’re crazy for knowing it too well.

This isn’t the starry-eyed excitement of first love. Del Rey sings with the air of someone who’s been there, done that, and found there wasn’t much to see. The awareness that it’s such a long shot is where the tragedy lies. An awareness that however self-destructive your behaviour, it’s still your best chance at satisfaction. Del Rey’s women may be uncertain of themselves but they’re striving for salvation. And in such high stakes, only total devotion like “You’re my cult leader, I love you forever” will do. LDR’s heroines aren’t “crazy” for not knowing what they’re doing; they’re crazy for knowing it too well.

I will love you till the end of time

Not only is love in Lanaland not first love, it’s often already past. Devotion is sung to past lovers, lost in the world. They die, walk out, disappear into “gang stuff”. And it’s not just the loss of past loves, but of innocence. “Fuck yeah, give it to me […] This is what I truly want, Is innocence lost” Del Rey sings, the scales dropping from her eyes, but that distancing delivery again gives hesitation. The hope of love is all the more desperate for having been proven fallible so many times before, awareness making hope harder to sustain.

I wish I were dead

Saying “I wish I were dead” in a song (like “Dark Paradise”, about a lover’s grief) is different from saying it in an interview. Especially when promoting Ultraviolence, a record that increasingly adopts the abandoned jazz singer mistress persona that both made and destroyed Amy Winehouse with Back to Black. Del Rey doing so prompted Frances Bean Cobain to tweet her that “The death of young musicians isn’t something to romanticize”. This wasn’t the first time LDR drew attention from Kurt Cobain’s relatives either – her cover of Nirvana’s “Heart-Shaped Box” led his widow Courtney Love to observe, “You do know that song is about my vagina right?” Kim Gordon’s book added, “If she really truly believes it’s beautiful when young musicians go out on a hot flame of drugs and depression, why doesn’t she just off herself?” Perhaps odd from a book that showers praise on Kurt, but then perhaps not for exactly the same reason.

Still very much of this mortal plane, Del Rey’s next move was a joint tour with none other than Courtney herself, and Honeymoon, the third chapter in the book of Del Rey, is expected in September. Have your little red party dress ready.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe