The streets throng with people outside Barbican’s bricked barricades. The day Suicide are holding their Punk Mass in London, not only is the Great City Race passing by but the London Underground’s enduring its first complete strike in 13 years. Faced with the introduction of potentially unlimited night shifts – with no extra pay – union members have shut down London’s subterranean circulatory system entirely, spilling its citizens out across the pavements. Many feel moved to point out all those who work worse hours and/or are paid far less – nurses and firemen, soldiers and bus drivers – but always from the viewpoint that everyone deserves to have it just as bad.

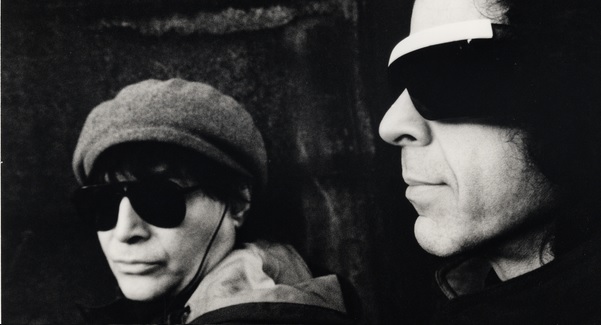

Under London’s scorching summer heat the streets are wired with a tension like the relentless hissing of Suicide’s early drum machines. A bare-bones configuration of vocals and electronics, Suicide’s arrival in late ‘70s, almost-bankrupt New York City was a shock no one had precedent for. Now the duo have a combined age of 144. They’ve made one album together in the last 23 years, and avowedly don’t rehearse.

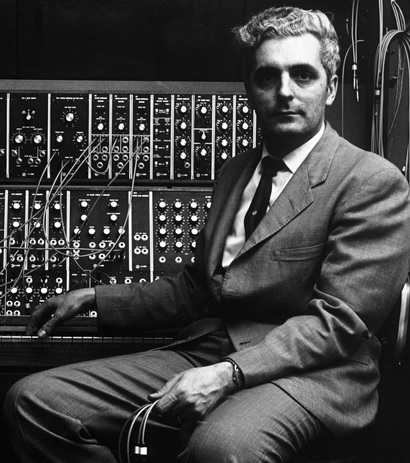

Tonight is part of Barbican’s Moog Concordance celebration of synths and a wall of rack-mounted Moog equipment twinkles and shines in the stage’s gloom, to be manned by Finlay Shakespeare. (Remember, that’s Moog as in Vogue, not Moog as in droog.) The lights dim and a chorus of 12 take to the stage, launching into a barrage of hellspawned bellyaching. It accelerates like a runaway ambulance ride through the city’s streets, reaching a simian furore. It’s terrifying, then hysterical, then cycles between the two. Each time you think it can’t go further, it does.

Safe to say, this probably isn’t going to be a greatest hits set.

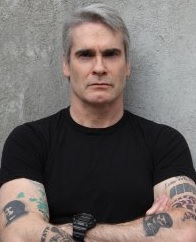

Rollins

Punk godhead, raconteur par excellence and onetime Black Flag frontman, Henry Rollins begins the show. Tearing another couple of pages from his intense journals, he recalls his first encounter with Suicide’s music and how he got to know vocalist Alan Vega. He describes the band’s ‘Frankie Teardrop’ (a kind of nightmarish reimagining of Bob Dylan’s ‘Ballad of Hollis Brown’, the story of a man who, unable to make ends meet, kills his young family and himself) as the heaviest song he’s ever heard, with the possible exception of ‘Strange Fruit’ (the same broad appreciation of intensity that fuels metal legend Phil Anselmo’s love of The Smiths). There are tales of the band’s legendary early days in New York (blood on the keyboard, facing down a CBGB’s audience) and he reads ‘Dead Man’ from Cripple Nation, the book of Vega’s writing published by Rollins’ own publishing house, 2.13.61.

Punk godhead, raconteur par excellence and onetime Black Flag frontman, Henry Rollins begins the show. Tearing another couple of pages from his intense journals, he recalls his first encounter with Suicide’s music and how he got to know vocalist Alan Vega. He describes the band’s ‘Frankie Teardrop’ (a kind of nightmarish reimagining of Bob Dylan’s ‘Ballad of Hollis Brown’, the story of a man who, unable to make ends meet, kills his young family and himself) as the heaviest song he’s ever heard, with the possible exception of ‘Strange Fruit’ (the same broad appreciation of intensity that fuels metal legend Phil Anselmo’s love of The Smiths). There are tales of the band’s legendary early days in New York (blood on the keyboard, facing down a CBGB’s audience) and he reads ‘Dead Man’ from Cripple Nation, the book of Vega’s writing published by Rollins’ own publishing house, 2.13.61.

Rev

Martin Rev, the musical component of Suicide’s pairing, panther-walks onto the stage in platform boots, wraparound shades and a shiny, sleeveless PVC jumpsuit. He proceeds to beat his Korg like it stole something from him, triggering absurd beats. Martin Rev is 67 and not fucking around. As The Velvet Underground mixed it with art-noise, as The Ramones mixed it with punk rock, and as Springsteen mixed it with good old fashioned rock and roll, so Suicide took the influence of girl-group R&B and mixed it with their austere electronic minimalism. The sumptuous harmonies of three backing singers tonight counterpoint Rev playing keyboard like a buzzsaw on sheet metal looking for transcendence. He twists and writhes on the spot, grinding his fist into the keys, guiding his singers and pushing the show to sensory overload.

Martin Rev, the musical component of Suicide’s pairing, panther-walks onto the stage in platform boots, wraparound shades and a shiny, sleeveless PVC jumpsuit. He proceeds to beat his Korg like it stole something from him, triggering absurd beats. Martin Rev is 67 and not fucking around. As The Velvet Underground mixed it with art-noise, as The Ramones mixed it with punk rock, and as Springsteen mixed it with good old fashioned rock and roll, so Suicide took the influence of girl-group R&B and mixed it with their austere electronic minimalism. The sumptuous harmonies of three backing singers tonight counterpoint Rev playing keyboard like a buzzsaw on sheet metal looking for transcendence. He twists and writhes on the spot, grinding his fist into the keys, guiding his singers and pushing the show to sensory overload.

Vega

Barely has Rev slunk from the stage and Alan Vega is led on. Vega is a terrifying presence on Suicide records – and his own, like the abrasive pulsations of 2010’s Sniper (with Marc Hurtado) or 1999’s glorious Righteous Lite (with Stephen Lironi, as The Revolutionary Corps of Teenage Jesus). He is tremulous, awestruck innocence and snarling disgust, snapping sharply between the two. He breaks down the twisted sides of life to explosive pop art, with genuinely unpredictable danger.

Barely has Rev slunk from the stage and Alan Vega is led on. Vega is a terrifying presence on Suicide records – and his own, like the abrasive pulsations of 2010’s Sniper (with Marc Hurtado) or 1999’s glorious Righteous Lite (with Stephen Lironi, as The Revolutionary Corps of Teenage Jesus). He is tremulous, awestruck innocence and snarling disgust, snapping sharply between the two. He breaks down the twisted sides of life to explosive pop art, with genuinely unpredictable danger.

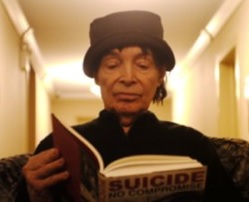

Sat on a throne, with a silver-topped cane and beanie hat, Vega has visibly aged. ‘I can barely walk!’ he barks. ‘Like the old days!’ He’s barely made a sound though when a thunderously fucking heavy industrial loop levels the room. He’s ably assisted by wife Liz Lamere and son Dante Vega, depth-charge bass and batteries of vocal samples, and dwarfed beneath towering video art of American flags writhing in the wind. He growls of visions and hallelujahs, stood staunchly on the stage, facing down age, fate and circumstance. It is a ridiculously exhilarating spectacle. The captain may be ailing but his vessel is still a fucking battleship, and it blows a venue open perhaps better than any I’ve seen bar Alec Empire.

Suicide

And then we have Rev and Vega united, the Suicide juggernaut itself. A chaotic stramash that takes in driving Krautrock, icy doo-wop and hammering techno. Rev has to coax and cajole Vega’s vocals (‘C’mon, daddy, tell me a story!’), often so muffled that the onslaught feels like a time-slipping fever dream. It shouldn’t work but it mostly does, and though they might not have to fight for recognition any more, Suicide are resolutely no museum piece. Even in the reverentially seated environs of the Barbican, the front of the stage is up and dancing, heckles are blurted out and security has to tackle stage invaders.

And then we have Rev and Vega united, the Suicide juggernaut itself. A chaotic stramash that takes in driving Krautrock, icy doo-wop and hammering techno. Rev has to coax and cajole Vega’s vocals (‘C’mon, daddy, tell me a story!’), often so muffled that the onslaught feels like a time-slipping fever dream. It shouldn’t work but it mostly does, and though they might not have to fight for recognition any more, Suicide are resolutely no museum piece. Even in the reverentially seated environs of the Barbican, the front of the stage is up and dancing, heckles are blurted out and security has to tackle stage invaders.

The wheels only really fall off when a greatest hits finale is attempted. For ‘Ghost Rider’, Rollins (who covered the song early in Rollins Band’s career) tries coaxing and provoking Vega to sing before cutting his losses and exiting the stage. ‘Dream Baby Dream’ leaves Primal Scream’s Bobby Gillespie (who absorbed, and arguably bettered, the song’s influence with XTRMNTR’s heart-shatteringly beautiful ‘Keep Your Dreams’) and Savages’ Jehnny Beth awkwardly just repeating the song’s title. Vega walks offstage into the arms of a minder, leaving Rev to pummel the beat into the floor.

So here’s what you get

A large part of why this still works is the same reason The Stooges’ 21st century albums work, or the obnoxious blast of adolescent fury that is Black Flag’s ‘reunion’ album What The… (of which Rollins was emphatically not a part). It revisits the same spirit without wishing to revere or recreate the band’s best-known work. It refuses to be sanitized.

At this point, Alan Vega can get applause just for standing up and walking across the stage – and he probably deserves it. So many times through the years he could’ve taken an easier path, edged onto the nostalgia circuit rather than just being ‘big in France’. If people wanted the legendary Suicide tonight – one of whose most notorious recordings was ‘23 Minutes Over Brussels’, named after the amount of time it takes their sonic assault to get booed offstage – well, they probably got closer than they think.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe