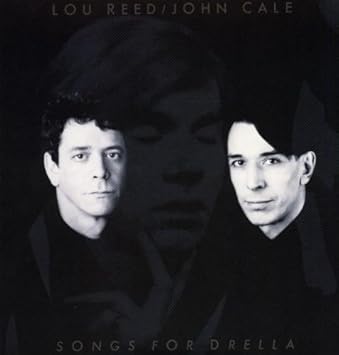

‘He said, “How many songs did you write?”

I’d written zero; I’d lie and say ten.

“You won’t be young forever. You should have written 15.

It’s work.”‘

– ‘Work’, Lou Reed & John Cale

In the later years of The Velvet Underground, Lou Reed began developing a form of portraiture in song, giving voices to those who might usually be left ignored or unheard.

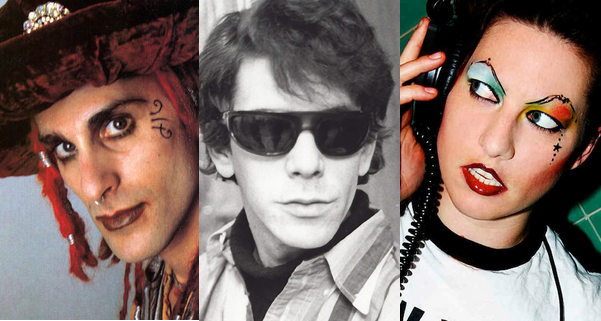

Holly Woodlawn

Andy Warhol’s studio, The Factory – where the VU spent much of their early years – was no stranger to portraits. Through film and fame, Warhol sought to elevate his associates to the status of ‘superstar’ – from Edie Sedgwick and Gerard Malanga, to the trans icons immortalised in Lou Reed’s ‘Walk on the Wild Side,’ Holly Woodlawn and Candy Darling. His screen prints were obsessed with – among other things – celebrity, immortalising iconic stars like Elizabeth Taylor and Marilyn Monroe. Visitors to The Factory – from Dennis Hopper to Salvador Dali – frequently found themselves left alone with their thoughts in front of a running camera, as part of Andy’s infamous ‘screen tests’, seeing how long their familiar facades would take to crumble. Andy’s art sought the egalitarian qualities in the elevated, and to raise the everyday and the excluded – the freaks and deviants, the weak and those discarded by ‘normal’ society – to the level of fine art.

The Factory was also no stranger to work ethic. Reed wrote the above lines for Songs for Drella, his audio biography of Warhol. (It takes its title from Andy’s drag name, looking half like Cinderella, half Dracula.) The song ‘Work’ reflects Andy’s approach of bringing mass production to fine art. Amidst the parties and the being seen, the sex and the drugs, The Factory was still a factory, and it had to produce product. As Andy adopted The Velvet Underground as his first musical project, for Lou that meant more songs. As The Velvet Underground’s career progressed, he found a simple technique for channelling his prolific songwriting. Songwriting is hard? Who says?

The Factory was also no stranger to work ethic. Reed wrote the above lines for Songs for Drella, his audio biography of Warhol. (It takes its title from Andy’s drag name, looking half like Cinderella, half Dracula.) The song ‘Work’ reflects Andy’s approach of bringing mass production to fine art. Amidst the parties and the being seen, the sex and the drugs, The Factory was still a factory, and it had to produce product. As Andy adopted The Velvet Underground as his first musical project, for Lou that meant more songs. As The Velvet Underground’s career progressed, he found a simple technique for channelling his prolific songwriting. Songwriting is hard? Who says?

Candy, Stephanie, Lisa and Caroline (1969-73)

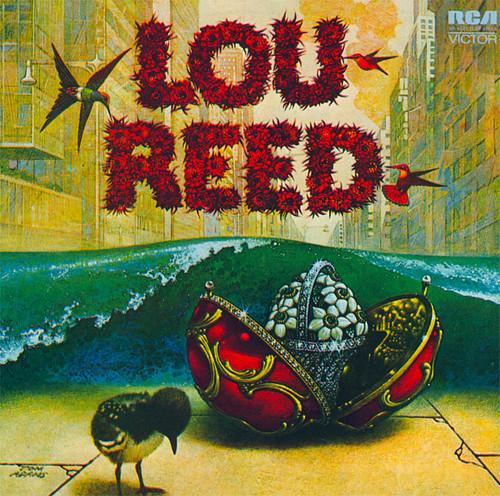

The appearance of ‘Candy Says‘ on The Velvet Underground’s eponymous third record inaugurates a thread that would run right through the dissolution of the band and into Lou’s first two solo records, Lou Reed and Berlin. The Factory scene was very much about ‘characters’, and by gathering clusters of impressionistic statements, Reed could quickly sketch fully fledged and compelling figures. The first thing Candy says – with a wistful shrug – is ‘I’ve come to hate my body / And all that it requires in this world’. If this was a line you overheard on the bus, you’d stay on those extra stops to see where this conversation’s going.

The appearance of ‘Candy Says‘ on The Velvet Underground’s eponymous third record inaugurates a thread that would run right through the dissolution of the band and into Lou’s first two solo records, Lou Reed and Berlin. The Factory scene was very much about ‘characters’, and by gathering clusters of impressionistic statements, Reed could quickly sketch fully fledged and compelling figures. The first thing Candy says – with a wistful shrug – is ‘I’ve come to hate my body / And all that it requires in this world’. If this was a line you overheard on the bus, you’d stay on those extra stops to see where this conversation’s going.

Candy is fretful and neurotic, existentially pondering what her potential could be if she could only get out of her own way, but the song isn’t judgemental. It keeps a respectful empathy as Candy confesses and confides. The delicate music of these songs almost seems to hush and lean forward, giving the speakers its full attention. These songs may not pass the Bechdel test – they are of course sung by a man and we don’t know who these women are talking to – but these female voices are talking about themselves and the songs are genuinely interested. They’re not who you might expect to meet as ‘girls in three-minute songs’.

‘Lisa Says‘ (cut for an abortive fifth Velvets record and resurrected on Lou Reed) tells us she’ll ‘do it with just about anyone’. She’s searching for solace in sex and action, but the line that her heart breaks ‘every time she makes it straight’ sets us wondering what it is about herself she could be running from. A large part of what makes this group of songs so compelling is that they leave unresolved. Wracked with emotion but getting on with their lives, they whisper their questions and fears into our ear, then slip off on their way. Lisa #2 is far more of a conversation, with the now-solo Lou equally confiding to the flirtatious Lisa that his insurmountable shyness means ‘those good times just seem to pass me by’.

‘Lisa Says‘ (cut for an abortive fifth Velvets record and resurrected on Lou Reed) tells us she’ll ‘do it with just about anyone’. She’s searching for solace in sex and action, but the line that her heart breaks ‘every time she makes it straight’ sets us wondering what it is about herself she could be running from. A large part of what makes this group of songs so compelling is that they leave unresolved. Wracked with emotion but getting on with their lives, they whisper their questions and fears into our ear, then slip off on their way. Lisa #2 is far more of a conversation, with the now-solo Lou equally confiding to the flirtatious Lisa that his insurmountable shyness means ‘those good times just seem to pass me by’.

Stephanie (another late Velvets outtake) has another killer opening line, wondering ‘Why she’s given half her life, to people she hates now’. Equal parts hapless absentmindedness and chilling isolation, Stephanie is another relatable and unresolved crisis, springing to life from the lyrics. Her ‘Alaska’ nickname and lack of fear of death are reincarnated, not once but twice, as Caroline, half of Berlin’s abusive speed freak love story. First cuckolding and promiscuous, later defiantly beaten and blankly self-harming, Caroline is a character of such complexity and depth that, rather than a one-shot portrait, she requires a full album to explore.

Stephanie (another late Velvets outtake) has another killer opening line, wondering ‘Why she’s given half her life, to people she hates now’. Equal parts hapless absentmindedness and chilling isolation, Stephanie is another relatable and unresolved crisis, springing to life from the lyrics. Her ‘Alaska’ nickname and lack of fear of death are reincarnated, not once but twice, as Caroline, half of Berlin’s abusive speed freak love story. First cuckolding and promiscuous, later defiantly beaten and blankly self-harming, Caroline is a character of such complexity and depth that, rather than a one-shot portrait, she requires a full album to explore.

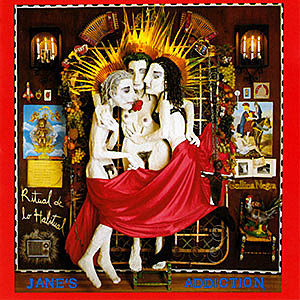

Jane (1987-88)

‘Jane Says’ is a song so good, Jane’s Addiction released it on their first and second records, in demo form, and in umpteen live renditions. A back-and-forth wash of breezy acoustic guitars, it originally appeared accompanied by bongo drums before donning its trademark rarest of rock instrumentation – steel drums! – courtesy of drummer Stephen Perkins. As an eavesdropping hook, Jane’s first proclamation – ‘I’m done with Sergio, he treats me like a ragdoll’ – is catnip. If Jane’s Addiction were trying to reintroduce rock and roll’s long-faded, free-spirited bohemia to late ‘80s LA, Jane’s every line contributes to that hazy aura of mystique. She’s hiding the TV, because she doesn’t owe Sergio nothing. She can’t find her wig, and feels naked without it. She’s going to save some money and move to Spain. And all of this is carried on the blissfully eternal junky mañana of the sunset singalong chorus: ‘I’m gonna kick tomorrow, Gonna kick tomorrow’.

‘Jane Says’ is a song so good, Jane’s Addiction released it on their first and second records, in demo form, and in umpteen live renditions. A back-and-forth wash of breezy acoustic guitars, it originally appeared accompanied by bongo drums before donning its trademark rarest of rock instrumentation – steel drums! – courtesy of drummer Stephen Perkins. As an eavesdropping hook, Jane’s first proclamation – ‘I’m done with Sergio, he treats me like a ragdoll’ – is catnip. If Jane’s Addiction were trying to reintroduce rock and roll’s long-faded, free-spirited bohemia to late ‘80s LA, Jane’s every line contributes to that hazy aura of mystique. She’s hiding the TV, because she doesn’t owe Sergio nothing. She can’t find her wig, and feels naked without it. She’s going to save some money and move to Spain. And all of this is carried on the blissfully eternal junky mañana of the sunset singalong chorus: ‘I’m gonna kick tomorrow, Gonna kick tomorrow’.

The irresolution between Jane’s dreams and the prospect that she might actually change nothing gives the lyrics their tension, and the song isn’t without Reed’s empathy either. Jane says ‘She’s never been in love / No, she don’t know what it is / She only knows if someone wants her’. Again, the song doesn’t judge or react, only listens. These songs put us right in front of confused and unguarded moments of intimate vulnerability. Jane is frustrated and emotional, prone to lashing out because ‘she just don’t know what else to do about it’. The song’s given extra weight by supposedly being drawn from a real person – frontman Perry Farrell’s former flatmate, Jane Bainter.

The irresolution between Jane’s dreams and the prospect that she might actually change nothing gives the lyrics their tension, and the song isn’t without Reed’s empathy either. Jane says ‘She’s never been in love / No, she don’t know what it is / She only knows if someone wants her’. Again, the song doesn’t judge or react, only listens. These songs put us right in front of confused and unguarded moments of intimate vulnerability. Jane is frustrated and emotional, prone to lashing out because ‘she just don’t know what else to do about it’. The song’s given extra weight by supposedly being drawn from a real person – frontman Perry Farrell’s former flatmate, Jane Bainter.

Blake (2008)

The strongest application of Reed’s ‘[name] says’ technique in recent years has come from Amanda (Fucking) Palmer. ‘Blake says no one ever really loved him / They just faked it to get money from the government’.

Sung by Palmer, ‘Blake Says’ gender-inverts the singer/subject of Reed’s work but also draws explicit reference to it. Blake ‘collects loose change for all tomorrow’s parties‘ (an early Velvets song sung by Warhol superstar Nico); ‘In his velvet mind … We’ll all go to Alaska when we die’. ‘Blake Says‘ inhabits a similar milieu to the Warholian world Reed portrayed, saturated with drugs (‘He takes his pills but never takes his medicine’), flitting relationships and isolation, but it’s updated for the 21st century (‘Blake like friends, but only for a minute, he / Prefers the things he orders from the internet’). Stephanie talking on a disconnected phone in Reed’s song is replaced with Blake having to actively avoid the connectivity of the modern world (‘Blake says he is sorry he got through to me, if it’s ok / He’ll call right back and talk to the machine’). Once again, the neutrality of the delivery means that Blake’s contradictory behaviour is portrayed in all its unresolved complexity. Palmer is like a ghost of Christmas future, letting us watch Blake but not interact or interfere; drawing the listener in but not directing them.

Sung by Palmer, ‘Blake Says’ gender-inverts the singer/subject of Reed’s work but also draws explicit reference to it. Blake ‘collects loose change for all tomorrow’s parties‘ (an early Velvets song sung by Warhol superstar Nico); ‘In his velvet mind … We’ll all go to Alaska when we die’. ‘Blake Says‘ inhabits a similar milieu to the Warholian world Reed portrayed, saturated with drugs (‘He takes his pills but never takes his medicine’), flitting relationships and isolation, but it’s updated for the 21st century (‘Blake like friends, but only for a minute, he / Prefers the things he orders from the internet’). Stephanie talking on a disconnected phone in Reed’s song is replaced with Blake having to actively avoid the connectivity of the modern world (‘Blake says he is sorry he got through to me, if it’s ok / He’ll call right back and talk to the machine’). Once again, the neutrality of the delivery means that Blake’s contradictory behaviour is portrayed in all its unresolved complexity. Palmer is like a ghost of Christmas future, letting us watch Blake but not interact or interfere; drawing the listener in but not directing them.

‘Name Says’ songs take time to focus on vulnerability, drawing attention to those who might slip through society’s cracks. They show the problems and the value in lives the mainstream might ignore but offer no easy solutions or resolution. They don’t tell you what to do, or if there’s anything that could be, only encourage empathy. Palmer’s mournfully meditative piano runs a tender thread back on tidal rolls of percussion, illustrating that whether you’re in early 1970s New York, late ’80s LA, or a millennial bedroom, regardless of how well they can be seen, the eccentric and the vulnerable are there. As Palmer notes, ‘It’s still cold in Alaska’, and a little empathy can go a long way. So listen to what they have to say.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe