Why do we still have ‘women’s fiction’ as a category in bookshops? Amazon, for instance, lists ‘Women Writers and Fiction Books’ as one of the major fiction categories, and ‘Women’s Popular Fiction’, ‘Women’s Literary Fiction’, and ‘Women’s Short Stories’ as further sub-categories. Why do we still think it is appropriate to label certain books ‘chick lit’? Women make up half the population, and yet, as Joanne Harris pointed out back in 2014, the publishing industry makes women out to be a minority. While fiction written by men about men’s daily lives is considered simply ‘fiction’, when written by and about women, it is given a sub-category label. This must stop.

By calling fiction of this kind ‘women’s fiction’, it perpetuates the myth that men won’t be interested in stories written by or about women. Where does this stereotype come from? After all, it is expected that women can and will enjoy books written by men, for men, about men… so why do we so readily accept the idea that interest in stories about certain genders can only go one way?

The importance of genre and bookshop categories

Categories are there to help readers. If you liked a book that was labeled ‘romance’, you are likely to go back to that section when looking for your next book. Agents, publishers, and marketers know this and use it when selling books. It’s useful. Certain genres have well-established genre tropes that readers expect to see when a book is placed in that category. And while I understand the usefulness of this system, the formulation of these categories can and does reflect ideology and bias.

To take a more in depth look, each category is defined by certain traits. Take science fiction and fantasy as examples. Science fiction features technology and science in its speculative worlds, whereas fantasy employs unknowable/purposefully inexplicable ‘magic’. Despite the contrast between nominally rational and irrational concepts in the stories, or the fact that one genre is notionally forward-looking, the other nostalgic, the two are more often than not grouped together. Does this reflect a poor understanding of the content on booksellers’ parts? No, it reflects the quite accurate assessment that many readers of science fiction also appreciate fantasy. Hence grouping them together optimises the exposure of a customer to potential purchases that appeal to them. From this utilitarian approach though, we can see that by simply grouping books together, assumptions are created and perpetuated about the implied reader.

To take a more in depth look, each category is defined by certain traits. Take science fiction and fantasy as examples. Science fiction features technology and science in its speculative worlds, whereas fantasy employs unknowable/purposefully inexplicable ‘magic’. Despite the contrast between nominally rational and irrational concepts in the stories, or the fact that one genre is notionally forward-looking, the other nostalgic, the two are more often than not grouped together. Does this reflect a poor understanding of the content on booksellers’ parts? No, it reflects the quite accurate assessment that many readers of science fiction also appreciate fantasy. Hence grouping them together optimises the exposure of a customer to potential purchases that appeal to them. From this utilitarian approach though, we can see that by simply grouping books together, assumptions are created and perpetuated about the implied reader.

So when we come to the contentious category in the bookstore, what does ‘women’s fiction’ actually mean? What is it saying about the implied reader? First off, women’s fiction is not romance. Not strictly, at least. The romance genre is an entirely separate shelving category. It may be marketed to women and proximal to the women’s fiction section but a distinction is being made. The key factors appear to be that romance is not necessarily written by women and delivers a highly conventional series of narrative tropes that the broader category of ‘women’s fiction’ does not need to adhere to. By comparison, is there something defining or consistent about this ‘genre’ of women’s fiction? The closest thing to a genre trope is the very broad observation that these books do focus on female protagonists who work through issues of everyday life. Therefore, the genre appears to be nothing more than realist fiction of either the literary or commercial bent with a female protagonist and writer.

Other than being written by women, about women, and marketed to women, there are no defining genre tropes to women’s fiction. A romance sub-plot isn’t a requirement, though it is common (then again, in what genre of book is a romance sub-plot uncommon?). They are often issue-led and explore issues from a focal character’s perspective, but the conclusion of the book can be positive or negative, the tone may vary wildly, and so forth. If there aren’t central tropes holding this genre together, it cannot be a genre at all. What we have is simply a literary ghetto for books, not based on their content or style, but based on the sexual demographic of their writer and protagonist.

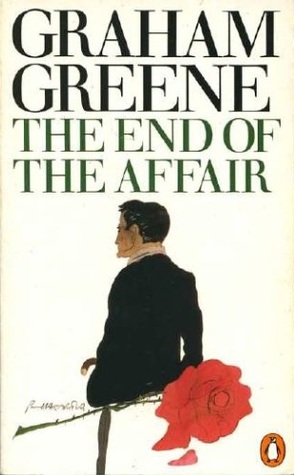

A Graham Greene case study

I’ve long been an enormous fan of Graham Greene’s writing. But when I look at much of his output, I have to wonder where the line of distinction is between his work and contemporary literary fiction that happens to be written by women. In many of his works, romance is a central theme – just look at The Heart of the Matter, The Quiet American, and The End of the Affair. These works are issue-led while also focusing on romantic relationships. The tone is similar to many titles that are classified as ‘women’s fiction’ but his works are noted as serious, literary, and marketed to both men and women.

I’ve long been an enormous fan of Graham Greene’s writing. But when I look at much of his output, I have to wonder where the line of distinction is between his work and contemporary literary fiction that happens to be written by women. In many of his works, romance is a central theme – just look at The Heart of the Matter, The Quiet American, and The End of the Affair. These works are issue-led while also focusing on romantic relationships. The tone is similar to many titles that are classified as ‘women’s fiction’ but his works are noted as serious, literary, and marketed to both men and women.

Greene was no stranger to being self-conscious about the genre labeling of his work. He even made a distinction between his ‘genre’ work, which he called ‘entertainments’ and his literary novels during his early career. Here was a man who was concerned about his literary reputation when writing in numerous different styles and genres. How about that – a writer being worried about being pigeonholed! Luckily for Greene, he was of the dangly genitalia variety, and so never suffered the way women still do when writing about anything. William Golding reportedly commented that Greene was ‘the ultimate chronicler of twentieth-century man’s consciousness and anxiety’ – something considered a lofty, literary pursuit. But if it were a woman writing about the female consciousness? Why, that would fall into that lesser category of ‘women’s fiction’!

Use your imagination

There is no need for books to be gendered in their marketing. The gender of the author and/or the protagonist doesn’t (or at least shouldn’t) make any difference to its appeal. No discerning reader restricts themselves to stories that repetitiously repeat their own perspective back at them. And even those readers that do can be enlightened and engaged by stories from perspectives they had not previously considered. This demographic pigeonholing is also contrary to any independent assessment of these books. Everything should rest on the kind of story (tone, plot, setting, etc) that is being explored. So instead of perpetuating the sexist bookshop category of ‘women’s fiction’, I suggest we use our imaginations, read outside of arbitrary boy-girl divisions, and define our books by the stories they tell rather than who wrote them.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe