You know how the story goes. Girl meets boy. Girl (or boy) lies about who they are and/or what their intentions are. Over the course of their subterfuge, they fall madly in love. The truth is uncovered and the object of their affection is hurt and angry. But love conquers all and they live happily ever after.

In other words, Shakespeare has a lot to answer for.

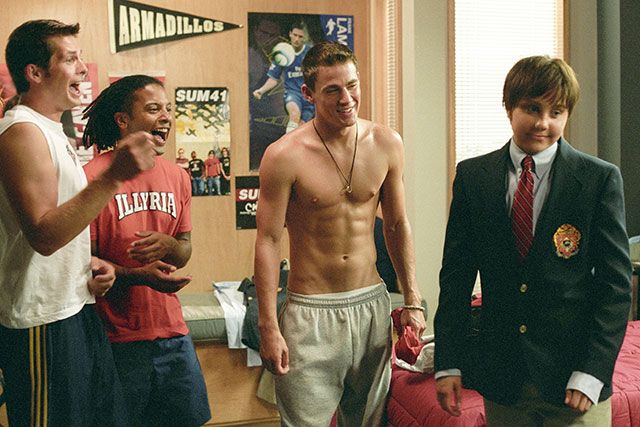

Nothing Shakespeare wrote was ever truly original, but his work has continued to have an enormous impact on our popular representations of romance. As You Like It, Twelfth Night, and The Taming of the Shrew feature characters pretending to be someone they’re not and winning their loves as a result. In truth, Shakespeare was writing in the much broader genre of New Comedy which he did not invent, but he nevertheless popularised the form and his works have a lasting impact on our culture. Teen films are often overlooked by critics and dismissed as insubstantial and predictable, but they do often turn to Shakespeare for inspiration. And if it’s good enough for Shakespeare… Twelfth Night is loosely re-imagined as She’s the Man and As You Like It is referenced in Never Been Kissed as a metaphor for the protagonist’s situation. Meanwhile, The Taming of the Shrew is vastly improved by the incredible 10 Things I Hate About You.

Nothing Shakespeare wrote was ever truly original, but his work has continued to have an enormous impact on our popular representations of romance. As You Like It, Twelfth Night, and The Taming of the Shrew feature characters pretending to be someone they’re not and winning their loves as a result. In truth, Shakespeare was writing in the much broader genre of New Comedy which he did not invent, but he nevertheless popularised the form and his works have a lasting impact on our culture. Teen films are often overlooked by critics and dismissed as insubstantial and predictable, but they do often turn to Shakespeare for inspiration. And if it’s good enough for Shakespeare… Twelfth Night is loosely re-imagined as She’s the Man and As You Like It is referenced in Never Been Kissed as a metaphor for the protagonist’s situation. Meanwhile, The Taming of the Shrew is vastly improved by the incredible 10 Things I Hate About You.

While the original folktale came before Shakespeare, the story of Cinderella that is closest to what we know today came from Charles Perrault in 1697 (this is the inspiration for the Disneyfied version) and the Brothers Grimm in 1812. In Cinderella’s transformation for the ball, she is presenting herself to be other than she is – a wealthy woman of high birth, not the servant girl who sleeps with the pigs. Her deception is rarely thought of negatively, given the abuse she has received from her step-family, but the deception is there all the same.

One of my personal favourite treatments of the Cinderella story is Ever After, which takes the deception elements to new levels. Instead of only appearing at the ball as a mysterious noblewoman, our ‘Cinderella’ has a prolonged period of deception as she develops a personal relationship with the Prince. On the one hand, this makes for a far more fulfilling story, where the audience can see their affections for each other blossoming (rather than some shallow ‘love at first sight’ nonsense), but on the other, her deception is far more morally questionable.

Hollywood has found that lies and manipulation over the course of an on-screen romance create great tension. You’ll be hard-pressed to find a romance film without at least some elements of deception on behalf of one or more of the protagonists. Often, instead of legitimate/necessary reasons for the deception occurring (such as being exiled with the threat of death if discovered), the reasons for the protagonist’s lies tend to be shallow and self-serving.

Hollywood has found that lies and manipulation over the course of an on-screen romance create great tension. You’ll be hard-pressed to find a romance film without at least some elements of deception on behalf of one or more of the protagonists. Often, instead of legitimate/necessary reasons for the deception occurring (such as being exiled with the threat of death if discovered), the reasons for the protagonist’s lies tend to be shallow and self-serving.

This occurred to me while watching one of my new favourite terrible but great films, Netflix’s A Christmas Prince. The main character is a reporter trying to get the scoop on the bachelor Prince and pretends to be the Princess’s new tutor as a way into the Prince’s private domain. This is hardly a life or death situation for her, but reporters are the scum of the earth… Her deception is forgiven as she debates whether or not to reveal the truth she has discovered and the ultimate unveiling of the story is perpetrated by others. But really, when it comes down to it, her choice to infiltrate the castle just for a glossy mag scoop is utterly despicable. (Let’s not even mention the terrible security around this fictional royal family…)

Reporters are no strangers to the lying method of romance. How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days features Kate Hudson as a magazine journalist who spends 10 days torturing a man in the name of a good story. Of course, she’d never get away with her behaviour if she a) weren’t so incredibly beautiful and b) it didn’t happen to coincide with the man’s own deceptive bet. What I liked about this approach (though, overall this film is really rather terrible – not that it has stopped me from watching it at least half a dozen times), is that both parties are equally dishonest. Do their lies somehow cancel each other out?

Reporters are no strangers to the lying method of romance. How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days features Kate Hudson as a magazine journalist who spends 10 days torturing a man in the name of a good story. Of course, she’d never get away with her behaviour if she a) weren’t so incredibly beautiful and b) it didn’t happen to coincide with the man’s own deceptive bet. What I liked about this approach (though, overall this film is really rather terrible – not that it has stopped me from watching it at least half a dozen times), is that both parties are equally dishonest. Do their lies somehow cancel each other out?

Despite the thoroughly morally objectionable nature of many of these stories, they are rarely called out for it. Interestingly, last year’s science fiction film Passengers is one of the few examples of such a love story hitting a bum note with audiences. What made this deception unforgivable? Where’s the line? Jim decides to ruin Aurora’s life for no other reason than he’s lonely and she’s attractive. You can mess someone around for a few weeks, but changing their lives in a way that they have no control over and no way to object and change the course? That’s too far. There should never be any coming back from that. And while the film initially frames his actions in a very negative light, it ultimately chickens out. Had the film been brave enough to acknowledge Jim’s behaviour as inexcusable, we would have had a far more interesting film.

Despite the thoroughly morally objectionable nature of many of these stories, they are rarely called out for it. Interestingly, last year’s science fiction film Passengers is one of the few examples of such a love story hitting a bum note with audiences. What made this deception unforgivable? Where’s the line? Jim decides to ruin Aurora’s life for no other reason than he’s lonely and she’s attractive. You can mess someone around for a few weeks, but changing their lives in a way that they have no control over and no way to object and change the course? That’s too far. There should never be any coming back from that. And while the film initially frames his actions in a very negative light, it ultimately chickens out. Had the film been brave enough to acknowledge Jim’s behaviour as inexcusable, we would have had a far more interesting film.

It’s no wonder that so many modern relationships fail. Our popular culture representations encourage us to lie and manipulate, but that it will all be alright if you really love each other. But I suppose that’s rather the point, isn’t it? These Hollywood films are all fantasy, whether they are modern reworkings of Shakespeare or Cinderella, or nonsense stories of single royals and hungry reporters… It’s worth remembering that honesty is the best policy.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe