The public first became acquainted with the detail-oriented, abrasive detective in 1887. We were subjected to his arrogant use of deductive reasoning for four novels and 56 short stories, but that wasn’t enough for the hungry audiences – we wanted more. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, Sherlock Holmes is the ‘most portrayed movie character’. Why is it that we are still obsessed with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s detective?

Crime procedurals and other detective/mystery related TV shows and films are ever present. Some of the longest-running and most successful TV series have been crime procedurals, such as Law and Order, CSI, NCIS, NYPD Blue, etc. Clearly, the minds behind TV and film have other ideas along the same vein, so why keep coming back to a character originally written over 100 years ago? What draws us back to Sherlock Holmes?

There is something to be said for familiarity – audiences like to see more of something they already like. We could be a little more skeptical and argue pure laziness on behalf of the studio execs. I don’t presume to have any definitive answer to the question, but I have my theories. The first is the personality of the enigmatic detective: he is unattainable in his very limited desire for human connections outside Watson (and especially not romantic connections), his arrogant, abrasive nature, and his predilection for drugs. His logical, ordered mind is at odds with the cleanliness and order of his home in a way that suggests a kind of obsessiveness, almost autism.

The second key feature of his enduring popularity is not his success at solving cases but the way in which he reaches his conclusions – his deductive reasoning. Another successful TV detective was all about the how – Columbo (which is also set to be rebooted with Mark Ruffalo taking on Peter Falk’s iconic role). In Columbo, the audience knew how the crime happened from the very beginning, the fascinating aspect of each episode was how the detective would figure it out. Sherlock Holmes, no matter what guise he is presented to the audience in, gives the audience two things: a mystery to be solved and a fascinating trip through a mind working through a puzzle. Audiences are intrigued by the mystery and how the detective solves it at the same time.

The second key feature of his enduring popularity is not his success at solving cases but the way in which he reaches his conclusions – his deductive reasoning. Another successful TV detective was all about the how – Columbo (which is also set to be rebooted with Mark Ruffalo taking on Peter Falk’s iconic role). In Columbo, the audience knew how the crime happened from the very beginning, the fascinating aspect of each episode was how the detective would figure it out. Sherlock Holmes, no matter what guise he is presented to the audience in, gives the audience two things: a mystery to be solved and a fascinating trip through a mind working through a puzzle. Audiences are intrigued by the mystery and how the detective solves it at the same time.

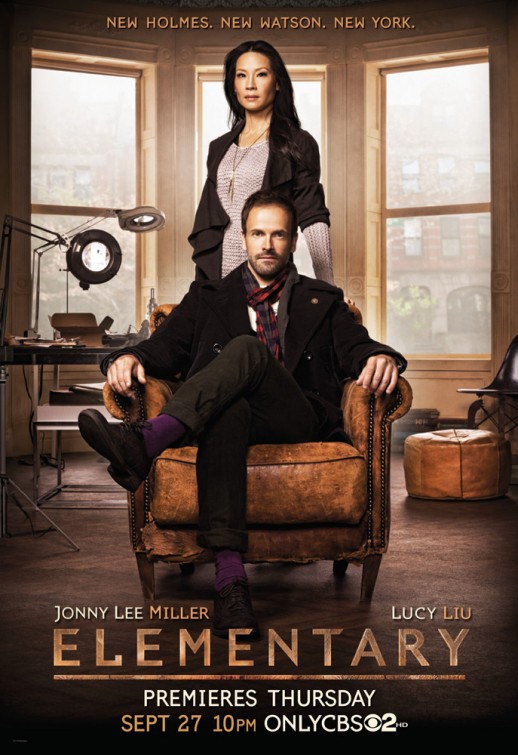

In recent years there have been three very successful adaptations of Sherlock Holmes on both the small and big screen: 1) Guy Ritchie’s Sherlock Holmes (2009) and it’s sequel Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (2011); 2) Sherlock (BBC, 2010–); and 3) Elementary (CBS, 2012–). I’ll be looking at how they interpreted the original source material and made it their own. (N.B. The nature of this article necessarily requires mild spoilers.)

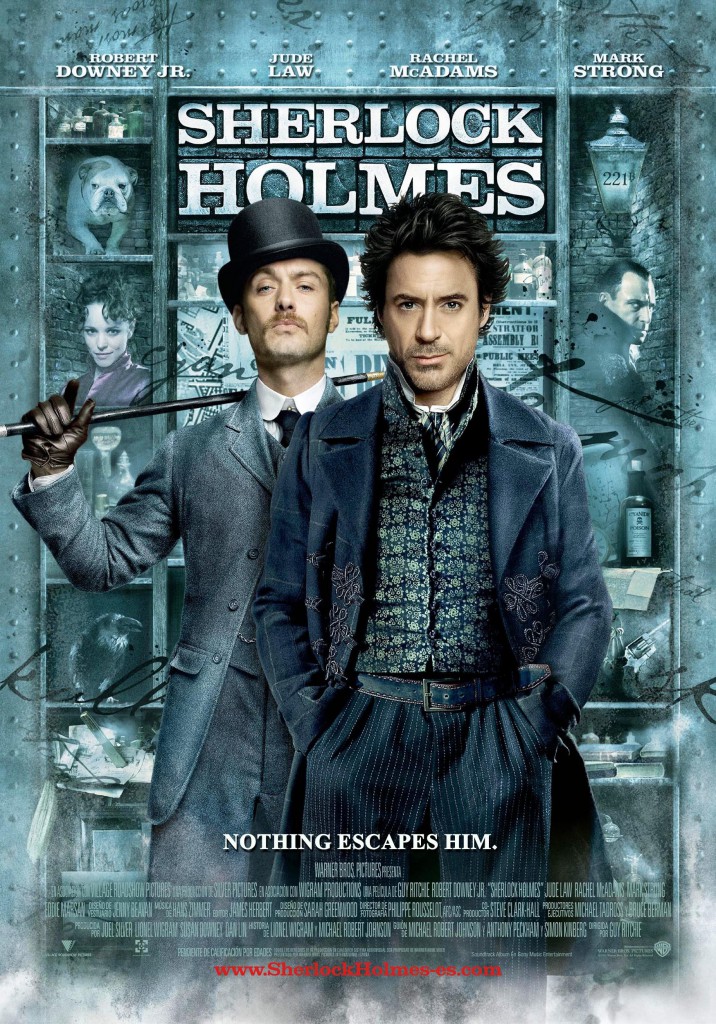

In Guy Ritchie’s adaptation, the story is still set in Victorian England as per its original source material. Robert Downy Jr stars as Holmes with Jude Law as Dr. Watson. Coming off the back of his successful portrayal of Iron Man, it seems that Downey Jr carried on playing the same part of the genius, billionaire, playboy philanthropist, only this time he lived in the 1800s. Even their ‘superpowers’ – brilliant minds – are basically the same. Ritchie did little to change up the original formula except add more comedy, action, and general bombast. Irene Adler is the only character to be strikingly different from the original, with much of her character completely invented for Ritchie’s version (although since her initial appearance in ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’, Adler has been used extensively in Sherlock Holmes productions with a much larger part to play).

In Guy Ritchie’s adaptation, the story is still set in Victorian England as per its original source material. Robert Downy Jr stars as Holmes with Jude Law as Dr. Watson. Coming off the back of his successful portrayal of Iron Man, it seems that Downey Jr carried on playing the same part of the genius, billionaire, playboy philanthropist, only this time he lived in the 1800s. Even their ‘superpowers’ – brilliant minds – are basically the same. Ritchie did little to change up the original formula except add more comedy, action, and general bombast. Irene Adler is the only character to be strikingly different from the original, with much of her character completely invented for Ritchie’s version (although since her initial appearance in ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’, Adler has been used extensively in Sherlock Holmes productions with a much larger part to play).

While Ritchie’s Sherlock films are fun, they teeter over the line into silliness. He chooses to use gimmicks, placing a high importance on Sherlock’s abilities with disguises to make the audience both laugh and remain in awe of Sherlock’s talents. Instead of being a brilliant, possibly autistic man, Holmes comes across more as a charismatic man unconcerned with social expectations (rather than being socially awkward he simply doesn’t care to conform).

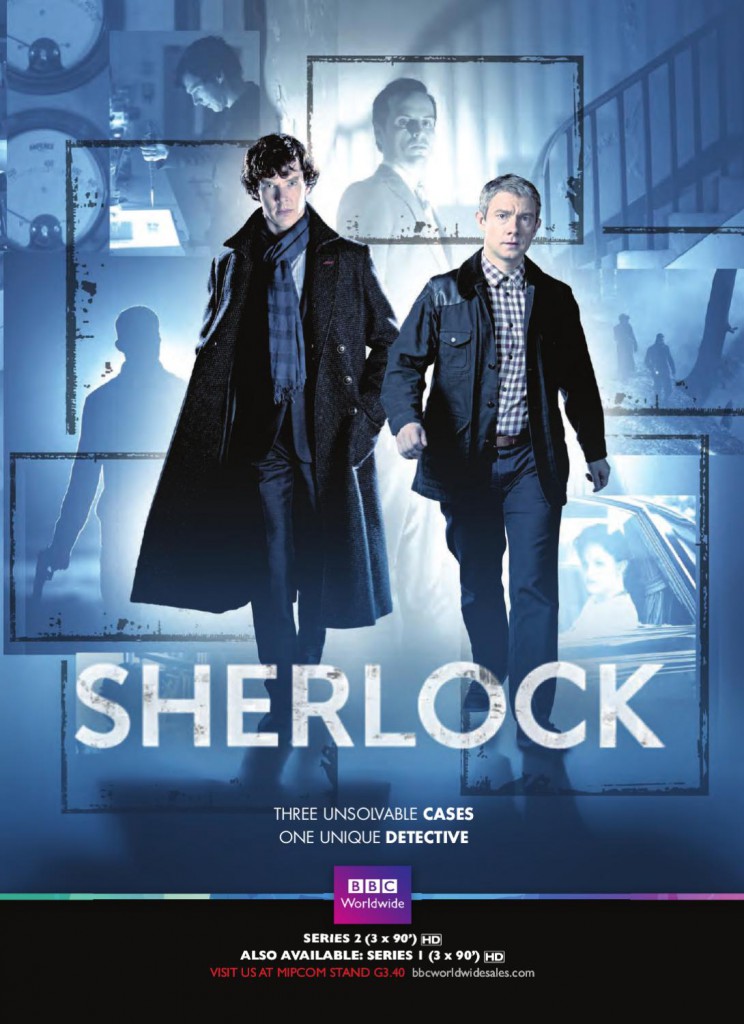

Arguably the most popular (and certainly the most critically acclaimed) adaptation in recent years, Mark Gatiss and Stephen Moffat created a modern-day version of the characters, though Sherlock himself remains remarkably unchanged. Watson has the most interesting story in the modern world, being a vet of Afghanistan, with his ‘publication’ of his doings with Sherlock taking the form of a blog. The relationship between Holmes and Watson grows in a natural and meaningful way, making their connection one of the strongest on-screen friendships I have seen in years, helping to create more emotional impact when dangerous situations occur.

Arguably the most popular (and certainly the most critically acclaimed) adaptation in recent years, Mark Gatiss and Stephen Moffat created a modern-day version of the characters, though Sherlock himself remains remarkably unchanged. Watson has the most interesting story in the modern world, being a vet of Afghanistan, with his ‘publication’ of his doings with Sherlock taking the form of a blog. The relationship between Holmes and Watson grows in a natural and meaningful way, making their connection one of the strongest on-screen friendships I have seen in years, helping to create more emotional impact when dangerous situations occur.

When it comes to the original material, the show’s creators have been good at incorporating the original material into the updated timeframe. For instance, Irene Adler makes her appearance in the episode entitled ‘A Scandal in Belgravia’ under similar circumstances to her original plot in ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’ (Holmes sent to retrieve incriminating photographs of a royal from her). Their ability to pick and choose just the right ingredient from the original material to include in their new stories (e.g. the hallucinogenic fog from ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’, the original death of Holmes and his subsequent return claiming to have ‘faked’ it for the benefit of his enemies, etc) provides a kind of authenticity while allowing for new, contemporary interpretations.

The series finds its biggest strength in its creation of well-rounded characters, which is a potential side effect of its longer film-length episodic structure. When it comes to mystery and/or detective-style stories, the emphasis is generally on the crime or mystery itself. Beyond elements of the detective’s own personality or backstory that allow him insight into the crime, there is often very little characterisation beyond the motivation for the killer to commit the crime. The characters in Sherlock are characterised in depth, far more than they ever were in the original material. They are each given their own sets of quirks, desires, and downfalls, ensuring that the audience has strong emotional ties with the protagonists as well as an interest in solving each of the cases.

Hot on the heels of success from across the pond, the US began developing its own modern remake of Sherlock Holmes. Unsurprisingly, creators of Sherlock were worried about copyright infringement on their predecessor. They had no need to be worries, however, as the two shows are markedly different. Again, the character of Holmes is left mostly un-tampered with. Instead of being a cocaine addict and occasional morphine user, he is a recovering heroin addict. However, this is in line with later stories of Doyle’s original, where Watson has helped Holmes kick the habit, though he claims the addiction is ‘not dead, but merely sleeping’.

Hot on the heels of success from across the pond, the US began developing its own modern remake of Sherlock Holmes. Unsurprisingly, creators of Sherlock were worried about copyright infringement on their predecessor. They had no need to be worries, however, as the two shows are markedly different. Again, the character of Holmes is left mostly un-tampered with. Instead of being a cocaine addict and occasional morphine user, he is a recovering heroin addict. However, this is in line with later stories of Doyle’s original, where Watson has helped Holmes kick the habit, though he claims the addiction is ‘not dead, but merely sleeping’.

The real stroke of genius in the series is with Watson: John Watson is now Joan Watson. Disgraced ex-surgeon and now sobriety companion living with Holmes for six-weeks after his exit from rehab. Much of the character-driven tension in the series relates to Watson, not Holmes, in that Watson is lost. She does not know what she wants to do with her life until she begins accompanying Sherlock on his investigations. Suddenly, she is invigorated and soon becomes Holmes’s apprentice. The ingenious gender-swap is, thankfully, not yet devolving into a mess of typical sexual tension between the protagonists. Showrunner Rob Doherty has said that a sexual relationship between Watson and Holmes is ‘off the table’.

Along with this update of Watson’s character, Mrs. Hudson, Holmes’s long-suffering housekeeper has also been updated. She is now a transgender ‘muse’, falling from one relationship to another, inspiring rich and creative men in their pursuits. Moriarty and Irene Adler have also been given a facelift, with them now being one and the same person. Irene being the guise in which she fell for Holmes and Moriarty being her criminal and brilliant alter ego.

***

Each of these new interpretations of Sherlock Holmes bring something to the table. But I’m still not sure why there is such a fascination with rebooting the same characters rather than creating new characters and scenarios in a similar vein – surely there is the potential for other brilliant detectives? Whatever the reason, it doesn’t look like Sherlock Holmes will be falling into obscurity any time soon, and if I’m honest, I’m not sorry.

However, I’m still amazed that one of the most beloved literary characters of all time was created by a man who believed in fairies and psychics. Oh well, I guess this is actually good news for all the weirdo writers out there – no matter how odd your personal convictions, if you’re writing’s good enough, audiences will focus solely at the merits of the piece of work itself.

However, I’m still amazed that one of the most beloved literary characters of all time was created by a man who believed in fairies and psychics. Oh well, I guess this is actually good news for all the weirdo writers out there – no matter how odd your personal convictions, if you’re writing’s good enough, audiences will focus solely at the merits of the piece of work itself.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe