Man Booker prize-winning author Kazuo Ishiguro has got a new novel out, The Buried Giant, which is causing something of a furore in literary circles. The battle is on the much-contested grounds of genre and is proving a classic example of the cultural biases that genre fiction tends to show up.

The Buried Giant is a novel following an elderly couple in Arthurian (or post-Arthurian) Britain. It has dragons, ogres and knights. However in an interview with the New York Times, the author has been a little more tentative about calling his book, with its overtly fantastical elements, a fantasy novel:

The Buried Giant is a novel following an elderly couple in Arthurian (or post-Arthurian) Britain. It has dragons, ogres and knights. However in an interview with the New York Times, the author has been a little more tentative about calling his book, with its overtly fantastical elements, a fantasy novel:

‘Will readers follow me into this? Will they understand what I’m trying to do, or will they be prejudiced against the surface elements? Are they going to say this is fantasy?’

Ursula Le Guin laid siege

Appropriately for a fantasy novel, or not if The Buried Giant isn’t one, open war was then declared. In response to Ishiguro’s statements and implications, acclaimed author and tireless champion of science fiction and fantasy Ursula Le Guin laid siege, saying:

‘Well, yes, they probably will. Why not? It appears that the author takes the word for an insult.’

Ursula Le Guin proceeded to expose the prejudices prevalent in this treatment of fantasy fiction in her article on bookviewcafe.com. The conflation of types of content with knee-jerk assumptions of quality is used to dismiss certain genres of fiction regularly. This is not news to many readers who find fantasy and other genres in a literary ghetto.

Ursula Le Guin proceeded to expose the prejudices prevalent in this treatment of fantasy fiction in her article on bookviewcafe.com. The conflation of types of content with knee-jerk assumptions of quality is used to dismiss certain genres of fiction regularly. This is not news to many readers who find fantasy and other genres in a literary ghetto.

This is a ramshackle genre ghetto

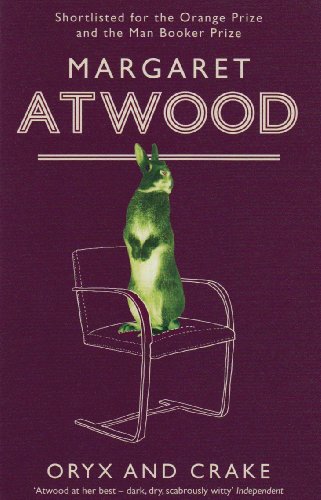

Indeed, Ishiguro’s reference to ‘surface elements’ is reminiscent of Margaret Atwood’s lamentable comments that she dealt in ‘speculative fiction’ rather than ‘science fiction’ when she was curiously taken aback by winning the Arthur C Clarke award in 1987.

We shouldn’t misconstrue this prejudice as simply the work of ‘those snobbish literary types’ though, as that kind of reductive mud-slinging has held back this debate for years. This is a ramshackle genre ghetto with many builders. The hostility and inaccessibility of various geek communities that laud fantasy and science fiction has been a major deterrent for people interested in these works. The ghetto might have been constructed by others, but some of those within have done much to perpetuate it.

We shouldn’t misconstrue this prejudice as simply the work of ‘those snobbish literary types’ though, as that kind of reductive mud-slinging has held back this debate for years. This is a ramshackle genre ghetto with many builders. The hostility and inaccessibility of various geek communities that laud fantasy and science fiction has been a major deterrent for people interested in these works. The ghetto might have been constructed by others, but some of those within have done much to perpetuate it.

This division of different spheres of writing (if they are so different) is a product of the book sellers and publishers too. Demographics must be categorised to be more easily targeted but this is not to the benefit of the reader who might be steered away from fiction because of its arbitrary shelving. Is Atwood’s Oryx and Crake such a departure from Brave New World that it needs to be in another section? Why is Philip K Dick’s counter factual history The Man in the High Castle so much less accessible than Rushdie’s fantastical retelling of the Indian independence Midnight’s Children?

Established authors have come out against the ghettoization of science fiction and fantasy

Hopefully, this will just be a minor setback in the discourse of genre discussions. More and more established authors have come out against the ghettoization of science fiction and fantasy in recent years.

Will Self has been a major proponent of science fiction, especially the works of J G Ballard, as a major driving force for literary innovation. Salman Rushdie has been quite unequivocating about the arbitrary distinction between fantasy and literary fiction, perhaps in response to several of his novel being patronisingly dubbed ‘magic realism’. He has previously said:

Will Self has been a major proponent of science fiction, especially the works of J G Ballard, as a major driving force for literary innovation. Salman Rushdie has been quite unequivocating about the arbitrary distinction between fantasy and literary fiction, perhaps in response to several of his novel being patronisingly dubbed ‘magic realism’. He has previously said:

‘The first premise of fiction is that it is not true. This story does not record events that took place. These people did not exist. These things did not happen […] Madame Bovary and a flying carpet are untrue in the same way.’

With any luck, this sort of enlightened thinking that seeks to open up the book shelves to all and sundry will get a bit more recognition from all quarters. Nevertheless, until that happens, try not to let the tired and disappointing suppositions of otherwise respectable authors limit what you read.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe