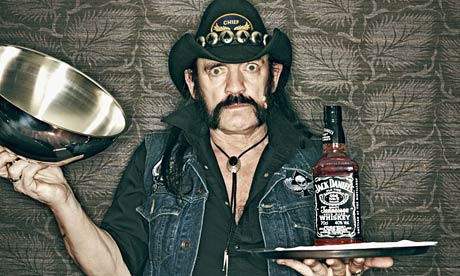

Lemmy Kilmister. Rock and roll icon. Former roadie for Jimi Hendrix. Leader, frontman and only remaining original member of Motörhead. The thunderous sturm und drang of Lemmy’s Rickenbacker has led the band through almost forty years of performance. He has the physique a (now admittedly aging) Norse god. While Keith Richards denied the lasting legend that he survived his prolonged heroin addiction by regularly travelling to a Swiss clinic to have his blood changed, Lemmy has admitted doctors advised him to avoid blood transfusions as he’d used amphetamine for so long, clean blood could be too great a shock for his system. Which is not to say Lemmy is blindly pro-drugs. Invited to share a platform at the Welsh Assembly with a Conservative AM, Lemmy voiced both his hatred of heroin and why it should be legalised.

Lemmy Kilmister. Rock and roll icon. Former roadie for Jimi Hendrix. Leader, frontman and only remaining original member of Motörhead. The thunderous sturm und drang of Lemmy’s Rickenbacker has led the band through almost forty years of performance. He has the physique a (now admittedly aging) Norse god. While Keith Richards denied the lasting legend that he survived his prolonged heroin addiction by regularly travelling to a Swiss clinic to have his blood changed, Lemmy has admitted doctors advised him to avoid blood transfusions as he’d used amphetamine for so long, clean blood could be too great a shock for his system. Which is not to say Lemmy is blindly pro-drugs. Invited to share a platform at the Welsh Assembly with a Conservative AM, Lemmy voiced both his hatred of heroin and why it should be legalised.

Motörhead’s motto (which is accurate) is Everything Louder Than Everything Else. Every show begins with Lemmy’s equivalent of ‘Hello, I’m Johnny Cash’: ‘We are Motörhead and we play rock and roll’. They’re a band worthy of the dictum John Peel ascribed The Fall’s greatness to: ‘They are always different; they are always the same’. They are loud. They are fast. Almost every album cover is a variation on their ‘war pig’ mascot. Arising around the dawns of both punk and the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, the band chose both paths (and so neither). Between rock, punk and metal, the Motörhead range over the years has taken in touches of thrash, rock and roll, blues, and heavier and slower, while maintaining the lyrical preoccupations befitting a rock band. But a man can’t write songs for forty years without needing some range.

Motörhead’s motto (which is accurate) is Everything Louder Than Everything Else. Every show begins with Lemmy’s equivalent of ‘Hello, I’m Johnny Cash’: ‘We are Motörhead and we play rock and roll’. They’re a band worthy of the dictum John Peel ascribed The Fall’s greatness to: ‘They are always different; they are always the same’. They are loud. They are fast. Almost every album cover is a variation on their ‘war pig’ mascot. Arising around the dawns of both punk and the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, the band chose both paths (and so neither). Between rock, punk and metal, the Motörhead range over the years has taken in touches of thrash, rock and roll, blues, and heavier and slower, while maintaining the lyrical preoccupations befitting a rock band. But a man can’t write songs for forty years without needing some range.

This autumn sees the release of Aftershock, Motörhead’s 21st studio album. Arriving on the heels of news that Lemmy (now 67) has diabetes/was fitted with a defibrillator/had to postpone tour dates due to an unexplained haematoma, it wears an appropriately battle-weary sleeve. As Lemmy and the boys commence another tour of duty, here’s a look back at an underappreciated facet of the Motörhead equation: the thread of socially conscious songs Lemmy has scattered through the band’s catalogue, putting the world to rights amidst the fast women, copious Jack Daniels and deafening, deafening noise. The top five:

This autumn sees the release of Aftershock, Motörhead’s 21st studio album. Arriving on the heels of news that Lemmy (now 67) has diabetes/was fitted with a defibrillator/had to postpone tour dates due to an unexplained haematoma, it wears an appropriately battle-weary sleeve. As Lemmy and the boys commence another tour of duty, here’s a look back at an underappreciated facet of the Motörhead equation: the thread of socially conscious songs Lemmy has scattered through the band’s catalogue, putting the world to rights amidst the fast women, copious Jack Daniels and deafening, deafening noise. The top five:

5. Lost in the Ozone (Bastards, 1993)

In 1992, a decade after their initial success dwindled, Motörhead signed to major label Epic and released an album called March Ör Die. It had glossier production. It had a single, with Ozzy and Slash, and everyone showing their sensitive, artistic sides. It was a failure.

1993, and back on an independent label, Motörhead upped the bludgeoning elements, dropped an album called Bastards and got back to business as usual. This plaintative effort paints Lemmy as the last, lonely survivor on a post-apocalyptic Earth, ravaged by the loss of its ozone layer (do you see the point he’s making here?). It also has that rare beast, a Lemmy bass solo, which is nice.

4. Don’t Let Daddy Kiss Me (Bastards, 1993)

This could easily have been one of those awkwardly over-earnest ‘issue’ songs rock bands can feel moved to record now and then, to prove they’re using their influence responsibly. Instead, Lemmy’s sincerity and bare bones delivery renders an incredibly uncomfortable and claustrophobic portrayal of child abuse. The guitar solo’s probably pushing it a bit though.

3. Just ‘Cos You Got The Power (b-side, 1987)

This swaggering, stalking epic is Lem’s indictment of money-crazed corporate swindlers, persecutive law enforcers, lying political classes and the powers that be in general, for their greed, abuse of power and generally lacking principles and humanity. As relevant in the ‘80s as it is today. And with some bananas soloing from Phil Campbell and Würzel, as well.

2. 1916 (1916, 1991)

Social conscience of Motörhead? Doesn’t Lemmy collect Nazi memorabilia?? Yes. Yes, he does. For the simple reason that he regards the world wars as interesting periods of history that shouldn’t be forgotten. While warfare may be stock subject matter for bands at the heavier end of the spectrum, here’s this. Lemmy, over synths, cello and martial drums – in the formal rhyme of the war poetry of Owen and Sassoon – recounting the tragic plight of an underage, forgotten soldier of the First World War.

Rather than heroic, Lemmy’s portrayal of soldiers is as sympathetic, undervalued and frequently betrayed figures of near-inconceivable endurance and sacrifice: ‘Food for the gun, That’s what you are when you’re soldiers’.

See also ‘March Or Die’ (March Ör Die, 1992), ‘Voices From The War’ (Hammered, 2002), ‘When The Eagle Screams’ (Motörizer, 2008).

1. No Voices In The Sky (1916, 1991)/Bad Religion (March Ör Die, 1992)/God Was Never On Your Side (Kiss Of Death, 2006)

You may have noticed a theme in the previous songs of unanswered prayers and God forsaking victims. Not a big fan of organised religion is Lem. Being the bastard son of a chaplain who walked out when he was three months old might be a factor, but opulent reserves of wealth, exploitation of the poor and arrogant moral hypocrisy don’t sit too well either. So, no God, no afterlife, no temperance of absolute death approaching. Lemmy faces implications squarely, and calls out televangelists while he’s at it. ‘Let the sword of reason shine’ indeed. Thus spake Kilmister.

And why does a Motörhead top five have seven songs? Overkill.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe