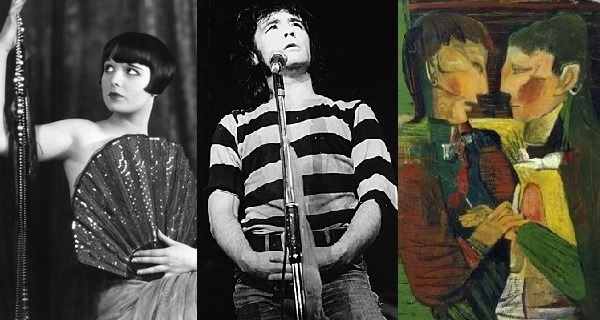

In 1929, stood silently on cinema screens, Louise Brooks was pure sex, in a black bob sharp enough to slit your throat. But the past is a different country, and it can be difficult getting a passport. We’re often given the impression that good art, no matter how long it takes, will be vindicated in time. Talent will out. Van Gogh, barely selling a painting in his lifetime, is now globally renowned. Even mere fragments of Sappho’s poetry remain in print, after two and a half millennia. This is the cream that rises to the top and forms the accepted canon.

The canon, however, is constantly reiterated, and it’s maintained by its gatekeepers: journalists, curators and critics; the moneymen and vested interests. Admittance is governed by the whim of those who direct our attention, and subject to the shifting tides of fashion. In time’s great river it’s easy to become sunk or washed up. Here are three such cases:

The Flapper

Louise Brooks left her tiny hometown of Cherryvale, Kansas to be a dancer in New York, landing in the Siegfried Follies revue that later hosted the legendary striptease artist Gypsy Rose Lee. She quickly became known for her risqué reputation of drinking and socialising. She had an affair with Charlie Chaplin and was repeatedly fired for her ‘superior attitude’ and arguing with other chorus girls – even being ejected from her hotel for ‘promiscuity’ – before her severe, doe-eyed aesthetic got her contracted by Paramount Studios. When cinema with sound arrived, studios took the opportunity to demand ‘contract concessions’, even from established stars, as it was unknown how audiences would take to actors once they were audible. Many careers were abruptly halted by unanticipated accents or grating tones, but Brooks was the only one to refuse the concessions outright, walking out to a job offer in Berlin.

It was director G.W. Pabst who cast her as Lulu in Pandora’s Box – a role she would render iconic. An innocent but unstoppable female sexuality that leaves a trail of destruction, including her own, in its wake, before falling into the clutches of Jack the Ripper. The performance was a sensation in Europe but, refusing to tame her behaviour amidst Weimar decadence, Brooks returned to the US, finding herself blackballed and no notice being paid to her European films, their having been eclipsed by the advent of the talkies. Her moment had been elided from history by the march of progress. Brooks was only rescued from penury and gin almost two decades later, when her neighbour put up posters to advertise a silent Louise Brooks film party at his apartment. He was startled to realise the reclusive neighbour now banging on his door with accusations of mockery was Brooks herself! Putting her in touch with a film archive, her still headstrong personality resurfacing added momentum to the critical reappraisal of her work.

It was director G.W. Pabst who cast her as Lulu in Pandora’s Box – a role she would render iconic. An innocent but unstoppable female sexuality that leaves a trail of destruction, including her own, in its wake, before falling into the clutches of Jack the Ripper. The performance was a sensation in Europe but, refusing to tame her behaviour amidst Weimar decadence, Brooks returned to the US, finding herself blackballed and no notice being paid to her European films, their having been eclipsed by the advent of the talkies. Her moment had been elided from history by the march of progress. Brooks was only rescued from penury and gin almost two decades later, when her neighbour put up posters to advertise a silent Louise Brooks film party at his apartment. He was startled to realise the reclusive neighbour now banging on his door with accusations of mockery was Brooks herself! Putting her in touch with a film archive, her still headstrong personality resurfacing added momentum to the critical reappraisal of her work.

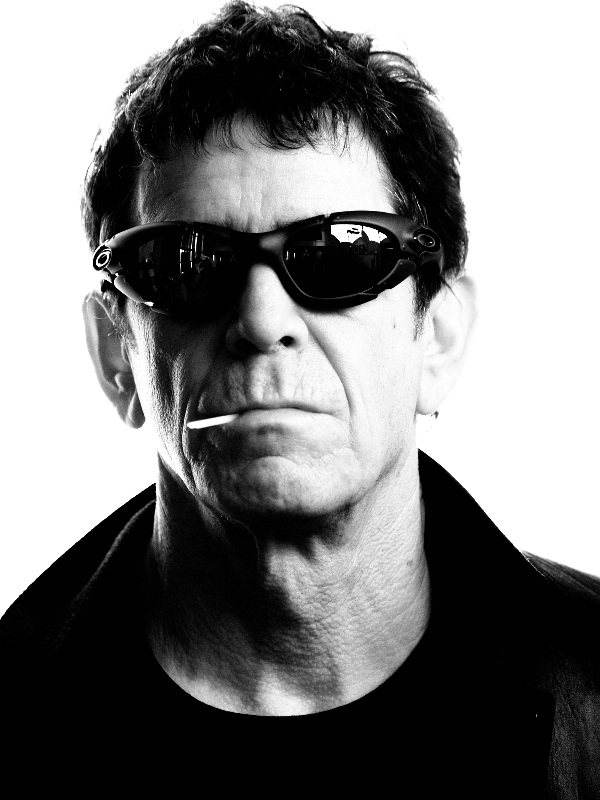

In this age of media saturation, we can travel through time with ease. A continuum of forgotten gems and neglected stars like these are at the ends of our fingertips in our omnidirectional postmodernity – with or without gatekeepers pointing the way. Follow the thread of Pandora’s Box, for example. It was adapted from two turn-of-the-century plays by Frank Wedekind – Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box – that had since become German theatre staples. While Brooks was filming, the plays were also being adapted as an opera by composer Alban Berg. Though he didn’t live to finish it, the opera has often been performed incomplete, and survives as the hunting sweep and loom of his Lulu Suite. The ‘Lulu plays’ were also the primary inspiration for Lulu, Lou Reed’s 2011 album with Metallica. I’ve sung the praises of Lulu in a previous article for this site but if you want to hear a 69-year-old man say ‘I swallow your sharpest cutter like a coloured man’s dick, blood spurting from me’ it remains your best port of call. Arterially dark and visceral, furiously raging and vulnerably, mournfully unresolved, Lulu has since become Lou’s final recorded work. I like to think he might’ve taken a little satisfaction in a work that provoked such notoriety and incomprehension becoming his musical headstone.

In this age of media saturation, we can travel through time with ease. A continuum of forgotten gems and neglected stars like these are at the ends of our fingertips in our omnidirectional postmodernity – with or without gatekeepers pointing the way. Follow the thread of Pandora’s Box, for example. It was adapted from two turn-of-the-century plays by Frank Wedekind – Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box – that had since become German theatre staples. While Brooks was filming, the plays were also being adapted as an opera by composer Alban Berg. Though he didn’t live to finish it, the opera has often been performed incomplete, and survives as the hunting sweep and loom of his Lulu Suite. The ‘Lulu plays’ were also the primary inspiration for Lulu, Lou Reed’s 2011 album with Metallica. I’ve sung the praises of Lulu in a previous article for this site but if you want to hear a 69-year-old man say ‘I swallow your sharpest cutter like a coloured man’s dick, blood spurting from me’ it remains your best port of call. Arterially dark and visceral, furiously raging and vulnerably, mournfully unresolved, Lulu has since become Lou’s final recorded work. I like to think he might’ve taken a little satisfaction in a work that provoked such notoriety and incomprehension becoming his musical headstone.

The Lovers

The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art earlier this year attempted a similar resurrection for two rock stars of British Modern Art. Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde met during their first week at Glasgow School of Art, in 1932. Quickly becoming inseparable, ‘the two Roberts’ (as they became known) moved in together but made it through Art School with virtually none of their acquaintances realising the two painters were also, in fact, a gay couple. So closely associated were they, that when one was awarded a grant to travel at the end of his degree, a faculty member gave the other the same amount from his own pocket, knowing they would just split it between themselves anyway.

The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art earlier this year attempted a similar resurrection for two rock stars of British Modern Art. Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde met during their first week at Glasgow School of Art, in 1932. Quickly becoming inseparable, ‘the two Roberts’ (as they became known) moved in together but made it through Art School with virtually none of their acquaintances realising the two painters were also, in fact, a gay couple. So closely associated were they, that when one was awarded a grant to travel at the end of his degree, a faculty member gave the other the same amount from his own pocket, knowing they would just split it between themselves anyway.

After forays in travel and military service, both arrived in the hard drinking Soho art scene of Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud, where the visually striking pair were huge successes, critically and socially. The rounded vibrancy of MacBryde’s still lifes and Colquhoun’s sharply angular figuration drew magazine coverage and gallery success. Almost as remarkable as the two Roberts’ art though, is the tragic arc of their story. Fashion moved on quickly, as it had arrived, leaving the heavy drinking pair reliant on friends. Colquhoun died, at 47, in MacBryde’s arms, having collapsed while working through the night on a potentially career-saving retrospective. MacBryde moved to Dublin, continuing to drink heavily, and four years later died after being struck by a car. When the two Roberts’ career renaissance came, they wouldn’t be around to see it.

After forays in travel and military service, both arrived in the hard drinking Soho art scene of Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud, where the visually striking pair were huge successes, critically and socially. The rounded vibrancy of MacBryde’s still lifes and Colquhoun’s sharply angular figuration drew magazine coverage and gallery success. Almost as remarkable as the two Roberts’ art though, is the tragic arc of their story. Fashion moved on quickly, as it had arrived, leaving the heavy drinking pair reliant on friends. Colquhoun died, at 47, in MacBryde’s arms, having collapsed while working through the night on a potentially career-saving retrospective. MacBryde moved to Dublin, continuing to drink heavily, and four years later died after being struck by a car. When the two Roberts’ career renaissance came, they wouldn’t be around to see it.

The Last of the Teenage Idols

And then there are those successes where you have to ask, How the fuck did that happen then? It’s a bewilderment you can see in the faces of Norwegian youths as – in 1974 now – they watch a diminutive, Dickensian, leather-jacketed 39-year-old Scotsman slick his hair back with beer, as his guitarist – dressed like a pansexual space alien in full-face clown make up – slowly cranks up the riff of ‘Framed’. This is the sensational Alex Harvey: Scotland’s greatest rock star.

Harvey certainly worked and waited long enough for his moment. From Glasgow’s notoriously deprived Gorbals area, Harvey was an early convert to the new craze of rock & roll. He toured rock and soul bands all over Scotland, supporting the likes of John Lee Hooker and Eddie Cochran. He did an apprenticeship of endless sets in Hamburg in the early ‘60s, and even won a 1957 newspaper competition to find the next Tommy Steele, before ending up in the London cast of hippie musical happening Hair. He released rock records and blues records, soul band records and solo records, but it was only with the recruitment of Glasgow prog band Tear Gas – 15 years younger than Alex – that The Sensational Alex Harvey Band was born.

Harvey was no stranger to modern art. Jacob Epstein’s towering, future-authoritarian Rock Drill sculpture adorns the SAHB album of the same name, while his second son Tyro takes his name from the Tyros of arch-Vorticist Wyndham Lewis (whose own Nazi-sympathy-tainted career has recently received a revaluation). And the SAHB were no straight ahead rock band. Even their more straightforward songs, like ‘Framed’ or ‘Faith Healer’, are loaded with a theatrical anguish, saturated with Alex’s shamanic charisma and thick Scots brogue. When they covered Jacques Brel – the Belgian singer-songwriter beloved of Scott Walker and Bowie – they didn’t just cover ‘Next’, Brel’s tale of virginity lost to an army-supplied prostitute, but did so as a tango of fevered hysteria, complete with string quartet.

Harvey was no stranger to modern art. Jacob Epstein’s towering, future-authoritarian Rock Drill sculpture adorns the SAHB album of the same name, while his second son Tyro takes his name from the Tyros of arch-Vorticist Wyndham Lewis (whose own Nazi-sympathy-tainted career has recently received a revaluation). And the SAHB were no straight ahead rock band. Even their more straightforward songs, like ‘Framed’ or ‘Faith Healer’, are loaded with a theatrical anguish, saturated with Alex’s shamanic charisma and thick Scots brogue. When they covered Jacques Brel – the Belgian singer-songwriter beloved of Scott Walker and Bowie – they didn’t just cover ‘Next’, Brel’s tale of virginity lost to an army-supplied prostitute, but did so as a tango of fevered hysteria, complete with string quartet.

The epic, tripartite bombast of ‘The Last Of The Teenage Idols’ casts back to the Tommy Steele contest for some hard-riffing rock & roll sung like Harvey’s on the edge of the world, before dropping into a doo-wop coda, while ‘Anthem’ is the bitter, ruefully melancholic and, yes, anthemic ballad of a wrongfully imprisoned man that often saw bagpipes and martial drums brought onstage.

SAHB made their name as an explosive live band. The band’s technical dexterity and sheer volume, Alex’s ringleader persona, and a raft of cheap and cheerful prop pieces conspired to win over any audience put in front of them. Years of paying dues on the live circuit also taught Alex the power of a good cover version. SAHB followed an old school approach to productivity – releasing 7 albums and a live record in their quick six-year existence, including plenty of covers. Tom Jones’s ‘Delilah’ and Del Shannon’s ‘Runaway’; ‘I Just Want To Make Love To You’ and even fellow theatrical rocker Alice Cooper’s ‘School’s Out’ – in which Harvey advises us not to “pish in the water supply”. First among equals in the SAHB covers catalogue though is ‘Tomorrow Belongs To Me’. Featured in Cabaret as a signifier of the rising Hitler Youth, by 1975 the German folk song was being adopted by neo-Nazis. Harvey’s seemingly straight and innocent, crooned version makes it wholly his own – that is, firmly not theirs.

SAHB made their name as an explosive live band. The band’s technical dexterity and sheer volume, Alex’s ringleader persona, and a raft of cheap and cheerful prop pieces conspired to win over any audience put in front of them. Years of paying dues on the live circuit also taught Alex the power of a good cover version. SAHB followed an old school approach to productivity – releasing 7 albums and a live record in their quick six-year existence, including plenty of covers. Tom Jones’s ‘Delilah’ and Del Shannon’s ‘Runaway’; ‘I Just Want To Make Love To You’ and even fellow theatrical rocker Alice Cooper’s ‘School’s Out’ – in which Harvey advises us not to “pish in the water supply”. First among equals in the SAHB covers catalogue though is ‘Tomorrow Belongs To Me’. Featured in Cabaret as a signifier of the rising Hitler Youth, by 1975 the German folk song was being adopted by neo-Nazis. Harvey’s seemingly straight and innocent, crooned version makes it wholly his own – that is, firmly not theirs.

Such pace and creativity can only burn for so long though. One of the few shown clemency by the punk new guard he was so fond of, the Sensational Alex Harvey Band nevertheless looked instantly outdated and ground to a halt in 1977. Harvey grew bogged down in alcoholism, debt and the physical pressures of aging, passing away five years later, a day shy of his 47th birthday. His guitarist, Zal, hung up his facial contortions to become a taxi driver. The SAHB back catalogue has only recently been resurrected by Sanctuary Records, who’ve performed similarly exemplary reissue exercises on the daunting back catalogue sprawls of Motörhead and The Fall.

Bands may be criticized for touring past their prime, but it’s still the surest way to keep your name on people’s lips. Art is big on legends but quick to forget, and not always justly. Great works remain out there, now only slightly hidden. Take a step outside the expert-approved pantheon and have a look around – all of recorded time awaits you.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe