How relevant is the singles chart these days? [*Note: The numbers used in this article refer to UK sales/streams only.] Now that streaming is counted along with sales (which is currently 150 streams to equal one ‘sale’), the charts have become even more skewed, disproportionally representing already established, massive pop acts. With big artists, they lead with perhaps one or two singles (unless, of course, you’re Beyonce, who doesn’t bother with lead singles at all anymore) before dropping the whole album. And what happens? No other artist gets a look-in. The chart will be dominated by track after track of the same artist, from the same album, for weeks on end.

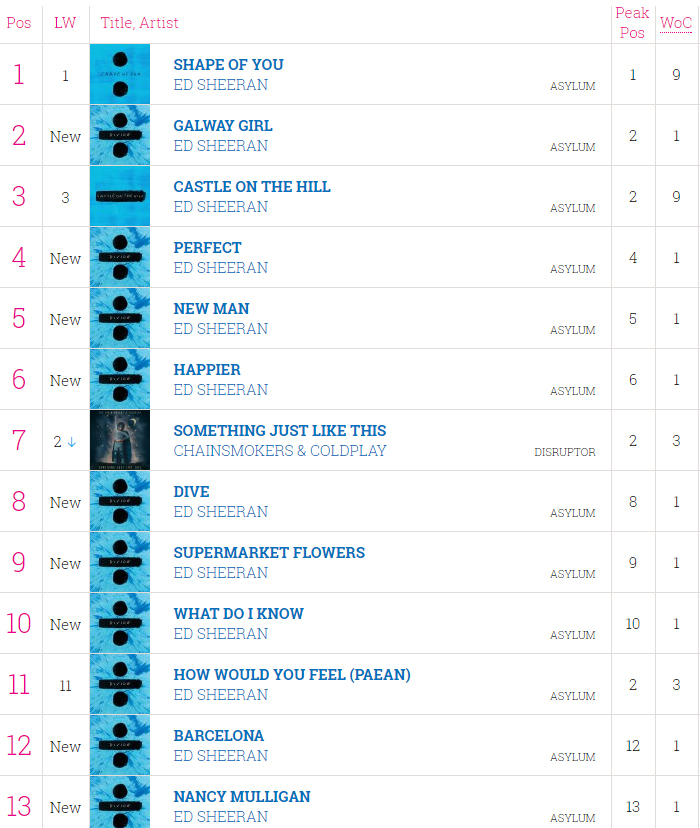

After his third album was released, Ed Sheeran found himself with an entire album in the UK singles chart (16 songs in the Top 40, with 79,000 album streams). Divided (‘÷’) became the fastest selling album by a male artist of all time. There was only one track by an artist other than Sheeran in the Top 10, and it was another obvious chart favourite (being performed by not one but TWO charting powerhouses):‘Something Just Like This’ by The Chainsmokers and Coldplay. This unprecedented level of chart domination has punters throwing their hands up in despair and demanding a change in how the charts are determined. But are their complaints justified?

After his third album was released, Ed Sheeran found himself with an entire album in the UK singles chart (16 songs in the Top 40, with 79,000 album streams). Divided (‘÷’) became the fastest selling album by a male artist of all time. There was only one track by an artist other than Sheeran in the Top 10, and it was another obvious chart favourite (being performed by not one but TWO charting powerhouses):‘Something Just Like This’ by The Chainsmokers and Coldplay. This unprecedented level of chart domination has punters throwing their hands up in despair and demanding a change in how the charts are determined. But are their complaints justified?

Now whether or not you’re a Sheeran fan (and I’m certainly *not* a fan of the latest album, it is the very definition of bland. Just http://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/22960-divide/read this review of the album, if you don’t believe me.), we can all understand the desire to play a new or favourite album on repeat. Sure, you’d have to listen to it 150 times before it is registered as a sale, but every single time you listen to that album or song, you are contributing to the charts, for better or worse.

With popular, well-established artists being listened to over and over (by those who have the time), the singles chart will continue to be skewed. How can a new artist hope to break into that? When charts were based solely on sales, singular or concentrated groups of uberfans could only significantly impact the charts if they had money to burn. But with streaming, each play of the song counts. They don’t even have to try to rig the system, their obsession simply fuels an already broken regime.

Not everyone likes to sit around listening to a single artist’s album. Sometimes variety is key – perhaps you want to find music that best speaks to a certain mood or time period, or even a particular style of music from a variety of artists. Streaming services have made themselves so desirable by the curation of content – and not just their own curation, but from the user community as well. In this way, arguably, discoverability of new artists is even better than it used to be. It is now unprecedentedly easy to ‘try out’ new artists. You can find them from a list of ‘related artists’ from an artist you already know and like, you might be listening to a curated playlist from the streaming service, or perhaps an artist you love has created a playlist of music they love. Finding music really has never been easier – but does that make it even harder to filter the crap from the gold?

Streaming has, supposedly, increased the staying power for singles. For instance, in 2016, Drake’s ‘One Dance’ topped the chart for a whopping 15 weeks, and Ed Sheeran’s ‘Shape of You’ has held the top position for 9 weeks so far this year. But if you bother to look waaaaaaay back in the chart history, you start to see that it was only in the 90’s and 2000’s where singles started having only one or two weeks at number 1, giving the chart a seemingly bigger variety. Was that really an indication of a better chart situation? Doesn’t it say something more about the quality of the singles, that none of them had the staying power to make it past that initial surge of uberfans lining up on release day to buy the new single?

Even long before streaming was an idea someone had, the singles charts were dominated for the most part by a few massive acts. Take the year 1965 as an example. There were a total of 26 number 1 singles over the course of the year. Of those 26, big bands took several spots each: The Rolling Stones and The Beatles with 3, and Elvis, The Hollies, and The Seekers with 2 each. Drake’s epic number 1 run was not the record holder, with Bryan Adams’ ‘(Everything I do) I do it for you’ topping the chart for 16 weeks back in 1991, and Wet Wet Wet’s 1994 single ‘Love is All Around’ matching Drake’s 15. Which begs the question, what’s changed? The complaints people are making about the charts being ‘taken over’ after the inclusion of streaming appears to be a matter of perception not borne out by the facts. This is how the popular music charts have always been.

In January, it was announced that streaming accounted for 80% of the UK singles market, prompting the change from 100 = 1 sale to 150. I disagree that this indicated an overestimation of the value of streams but rather reflects the changing nature of music consumption. Sure, I might still buy CDs, but I’m definitely in the minority. More and more of us find ourselves listening to music via streaming. That’s hardly going to change. Let’s stop griping about it and start thinking more about how many opportunities it gives the average music lover to find and explore new and different genres and artists.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe