Are we too nostalgic for the past? Why do the deaths of celebrities, even those who were the voices of generations long before our own, provoke such public exhibitions of mourning? In all art, we recycle and borrow from the past. We are all products of our time, our influences, our experiences. Whether overt or not, I have come to believe that even the most ‘forward-thinking’ and controversial artists produce work that is, to some extent, elegiac. Everything we create – and will create – laments and pays homage to the past in one way or another.

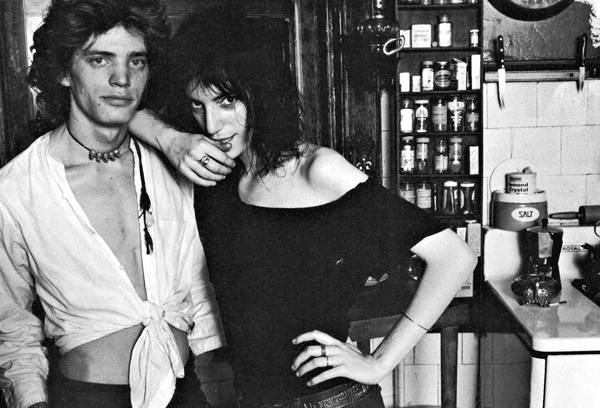

The blurb for Patti Smith’s biographical book, Just Kids, purports that it ‘begins as a love story and ends as an elegy.’ While this back cover copy is referring to Smith’s relationship with fellow artist Robert Mapplethorpe, which is the centre-piece of the book, I noticed a melancholy fixation with artists dead and gone both in Smith’s recollection of her past life and inspirations, as well as looking back on the friends from her own life she has lost along the way. And she is hardly alone in these musings, even within the text. She and her friends mourn celebrities they never knew, from long ago as well as their contemporaries, from her personal obsession with Rimbaud (which continues to this day – she recently purchased his reconstructed home) to a more general malaise at the loss of icons like Brian Jones, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix (though the latter two differed in that Patti had met both before their untimely deaths).

The blurb for Patti Smith’s biographical book, Just Kids, purports that it ‘begins as a love story and ends as an elegy.’ While this back cover copy is referring to Smith’s relationship with fellow artist Robert Mapplethorpe, which is the centre-piece of the book, I noticed a melancholy fixation with artists dead and gone both in Smith’s recollection of her past life and inspirations, as well as looking back on the friends from her own life she has lost along the way. And she is hardly alone in these musings, even within the text. She and her friends mourn celebrities they never knew, from long ago as well as their contemporaries, from her personal obsession with Rimbaud (which continues to this day – she recently purchased his reconstructed home) to a more general malaise at the loss of icons like Brian Jones, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix (though the latter two differed in that Patti had met both before their untimely deaths).

Modern media has both cultivated and maligned the ‘cult of celebrity’ and how it evokes a public ‘show’ of grief at the passing of every famous (or once-famous) name. But the endless news flashes overlook the fact that the statements from other famous people on the dead are hardly an important outcome of such a loss – what is important is the art that will be created in memory of, in imitation of and inspired by the departed artist.

Lost potential or OTT sentimentality?

The internet is a wonderful thing. We have access to so much information that would have otherwise been lost to the annals of time – or at least to anyone who wasn’t a historian in a specific area. What do I mean by this? Before the internet, it was much harder to discover old films, music, books, and so on. But now we have access to almost everything that was ever created and the issue becomes how do you wade through all of that content?

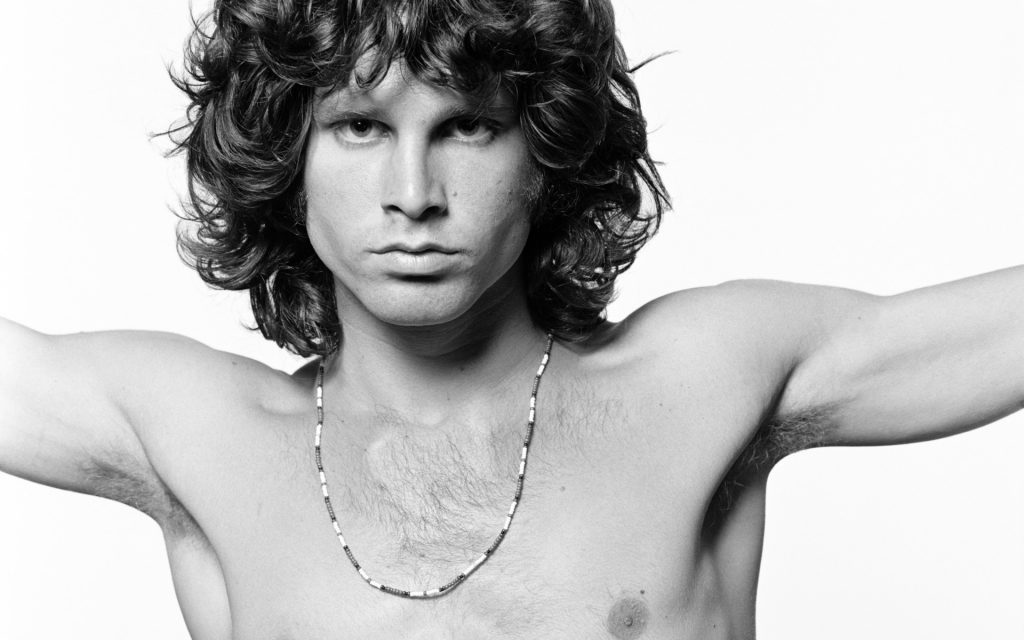

Whereas back in Smith’s day (at the risk of making sweeping generalisations and sounding overly nostalgic), the deaths that impacted the public most were often young people struck down in their prime, these days the sad deaths are more often from cancer or other long-term chronic illness. The drug overdoses and suicides are less common – though when they do occur, are still as devastating as they ever were (Amy Winehouse, Heath Ledger, Prince). Those who once mourned were the contemporaries of these great artists, mourning the loss of someone who gave voice to a generation – their generation. What would Janis Joplin had achieved if she lived on? Would The Doors still be going strong like The Rolling Stones if Jim Morrison hadn’t died so young? We will never know and this is what makes their death so painful.

Whereas back in Smith’s day (at the risk of making sweeping generalisations and sounding overly nostalgic), the deaths that impacted the public most were often young people struck down in their prime, these days the sad deaths are more often from cancer or other long-term chronic illness. The drug overdoses and suicides are less common – though when they do occur, are still as devastating as they ever were (Amy Winehouse, Heath Ledger, Prince). Those who once mourned were the contemporaries of these great artists, mourning the loss of someone who gave voice to a generation – their generation. What would Janis Joplin had achieved if she lived on? Would The Doors still be going strong like The Rolling Stones if Jim Morrison hadn’t died so young? We will never know and this is what makes their death so painful.

But now, we are starting to see the passing of legends and powerhouses that may have had their ups and downs, but have had a sustained and lasting impact on their area of creative arts. These are musicians like Bowie, actors like Alan Rickman, comedians like Rik Mayall, and more. But while the work they produced up to their death may have been solid, it is rarely at the level that established them as greats. This mourning has less to do with the loss of potential and more about admiration and due respect.

While I am not suggesting there is no reason to be emotionally affected by the death of anyone, whether you personally knew them or not, but the showmanship of public mourning that is so often associated with such losses has grown out of proportion. No longer is it about the loss of someone who voiced the feelings of a generation or even a sentimentalised view of a long creative and productive history. Instead, these deaths are used as a way to show off performed empathy and your cultural knowledge. Being saddened by the death of Bowie means you know and love his work, which in turn makes you a human of taste and wide cultural experience, right? In the age of the selfie and social media, public mourning is just another act devoid of real emotion, admiration, or artistic merit.

The fear of death

Our necessary mortality will always be at the heart of the human experience and expression. We fear death and cling to the possibility of finding not only eternal life but eternal youth. It is a common comment to make that artists create in order to live on after death. But can leaving a legacy really negate that innate fear of mortality? Reading Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Professor Yuval Noah Harari, I came across this note on Woody Allen’s perspective: ‘Woody Allen, who has made a fabulous career out of the fear of death, was once asked if he hoped to live on forever on the silver screen. Allen answered “I’d rather live on in my apartment.” He went on to add that “I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work. I want to achieve it by not dying.”’ He has a point, no?

Our necessary mortality will always be at the heart of the human experience and expression. We fear death and cling to the possibility of finding not only eternal life but eternal youth. It is a common comment to make that artists create in order to live on after death. But can leaving a legacy really negate that innate fear of mortality? Reading Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow by Professor Yuval Noah Harari, I came across this note on Woody Allen’s perspective: ‘Woody Allen, who has made a fabulous career out of the fear of death, was once asked if he hoped to live on forever on the silver screen. Allen answered “I’d rather live on in my apartment.” He went on to add that “I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work. I want to achieve it by not dying.”’ He has a point, no?

Is our public mourning of the loss of an artist our way of acknowledging both the mortality of the body and the immortality of art?

Imitation: the sincerest form of flattery

As creators of art, we are also natural consumers. You want to develop your skill, learn how to do something well? Seek out those who have gone before you, see what they did, learn from their mistakes, develop your own style. When you find something you like, why not appropriate it and make it into something new? As the story goes, when Prince first heard Kate Bush’s song ‘Cloudbusting’, he was obsessed. He loved it so much he attempted to write his own song in a similar style – the influences of it can be heard on his album Around the World in a Day with tracks like ‘Raspberry Beret’ and ‘Paisley Park’. No artist is too big, too small, well-known, gifted in their own style, etc to be inspired by others around them. Taking something you’ve seen before and putting your own spin on it is as legitimate a form of artistic creation and expression as anything else.

A common writing exercise involves writers either emulating a particular writer’s style or to use actual pieces of another writer’s work to springboard off from. If you have always loved Nabokov’s Lolita, why not attempt to write in that style and see what you learn? You will be amazed at what you pick up in the process – the writer’s ticks, the vocabulary, sentence structure, and more. But this can be problematic as well. If you spend too much of your time imitating others, you may stifle your individual voice. What makes you you? What do you have to say that is unique to you and in a style all your own?

Do we become too stuck in the past, always looking back, lost in nostalgia? Those voices that struck a chord with so many were often those concerned with innovation and exploration. If those same voices were obsessively focusing on the past, would they have been so vital? While being mindful of influences and inspirations from the past, we need to be careful that our elegiac nature does not stifle our creative growth.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe