It is a very worthy cause to include diverse roles and representation within film. Representation has long been an issue in the film industry, from race to age to gender to sexual orientation, any minority you can think of has often been underrepresented by both characters and actors. We have previously discussed the problematic prevalence of whitewashing in Hollywood, but the most recent controversy to rear its head is the casting of able-bodied actors in place of disabled actors to portray disabled characters.

This issue has flared up in the public consciousness after Alec Baldwin was announced to star in Blind, portraying a blind character, as indicated by the rather on-the-nose title. Is this just another cynical casting from Hollywood producers who think a film will only do well with a big name attached or an attempt by Baldwin to win an Oscar for his portrayal of a person with disabilities? After all, it has been found that ‘16% of Oscars for best actor had been awarded to those playing characters with a mental or physical disability‘. As noted by The Atlantic several years ago, ‘casting entails more than a search for diversity’. Whatever the likely pathetic excuse for this casting choice is, it is important to consider the casting in context and not immediately write off all casting choices as ‘ableist’.

This issue has flared up in the public consciousness after Alec Baldwin was announced to star in Blind, portraying a blind character, as indicated by the rather on-the-nose title. Is this just another cynical casting from Hollywood producers who think a film will only do well with a big name attached or an attempt by Baldwin to win an Oscar for his portrayal of a person with disabilities? After all, it has been found that ‘16% of Oscars for best actor had been awarded to those playing characters with a mental or physical disability‘. As noted by The Atlantic several years ago, ‘casting entails more than a search for diversity’. Whatever the likely pathetic excuse for this casting choice is, it is important to consider the casting in context and not immediately write off all casting choices as ‘ableist’.

Acting is just that: acting

Acting, by very definition, means pretending to be someone else. Whether that is simply pretending to be a lawyer without a law degree, an American when you are British, someone from another century, or a person with a disability when you are able-bodied, all acting involves re-inventing yourself as someone else for the duration of a film or play. Any argument that says only an actor who ‘accurately’ represents the character should be allowed to portray them has some obvious problems. No one alive has first-hand experience of living in Jane Austen’s time, but this doesn’t restrict us from producing adaptations of her work. This reasoning is obviously extreme, but the point illustrates that a unilateral imposition of a ‘no unrepresentative casting’ rule with no attention paid to context is absurd and untenable. There are lines of reasoning that can be discerned to justify a given casting.

When taking on any role, an actor will need to do research. What was it like to be a soldier in World War I? What was it like being a Victorian coal miner? We’d be naive to assume no insight was gained in an actor’s researching the life of a transgender or person with a disability. And where is the line when we have extant people of these backgrounds rather than unattainable historical groups? If it is okay to have a Brit play an Australian, what about a Thai actor playing someone Chinese? A key distinction to be made is, as ever, power dynamics. Groups who exercise less power and self-determination in society, if not outright persecution, can see their marginalisation furthered by media portrayals that may firstly stereotype them and then perpetuate their exclusion from public platforms, like the media. No one in the Regency period loses out from a shoddy casting call for Persuasion. Not only are characters with disabilities often solely defined by that trait, but these limiting roles don’t even provide a leg-up for members of that community.

At the very least, we want to see actors with disabilities in all kinds of roles, not just roles written with their disability in mind. In X-Men: Days of Future Past, for instance, there is nothing about the character of Dr. Trask that seems to require an actor with dwarfism. So why, then, did the role go to Peter Dinklage? Whether by virtue of his box office draw or his acting talent, he was simply deemed the best person for the job. If saying that only someone with a specific disability should be allowed to portray a not-specifically disabled character on-screen, does the opposite also follow? That is complicated by how disabilities can begin or develop.

Some characters necessitate able-bodied actors to represent a pre-disabled state

How do you represent a transitional state for these stories with a disabled actor? For instance, in The Theory of Everything, Eddie Redmayne’s portrayal of Stephen Hawking includes the degeneration of the man’s muscles and mobility. If a film focuses, for the most part, on a character in a wheelchair, it might still require a period where that character was able to walk. What then? There isn’t always a sibling who can play the pre-transition version of a transgender actor as they did for Laverne Cox’s character on Orange is the New Black.

Some argue that this is just another excuse for Hollywood to exclude disabled actors. If I were being cynical, I might agree, but I think there is more to it than that. Stories of those who suffer trauma or an illness that causes them to develop a disability and how they have dealt with that transition are important and worthy stories to tell, just as those of someone who may have been born with their disability.

Some argue that this is just another excuse for Hollywood to exclude disabled actors. If I were being cynical, I might agree, but I think there is more to it than that. Stories of those who suffer trauma or an illness that causes them to develop a disability and how they have dealt with that transition are important and worthy stories to tell, just as those of someone who may have been born with their disability.

One commentator noted another potential reason for why able-bodied actors portray disabled characters. Christopher Shinn conjectured that these portrayals ‘provide us with the comforting assurance that we are not witnessing the actual pain and struggle of real disabled human beings; it is all make believe.’ I fear that this is a step too far over the cynical line, but he may well have a point. A lot of our media is based around reassuring and coddling us, even when it claims to challenge and enlighten us.

Enough with the clichés already

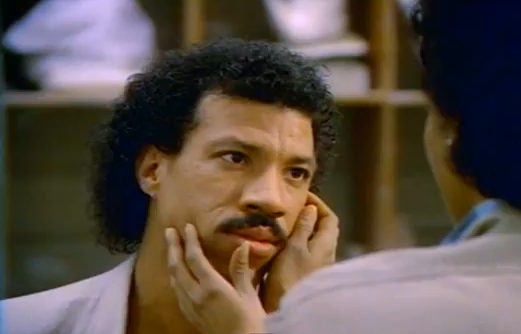

One of the biggest problems compounding this is not necessarily the casting, but the clichés written into the characters they portray. This is a notorious problem with the representation of blind characters, so I can understand viewers’ trepidation at Baldwin’s Blind. How many times do we need melodramatic scenes of a blind person feeling their loved one’s face (I immediately think of Lionel Richie’s video for his song ‘Hello’ – cringe city) as the music swells in the background? We seem to only end up with stories of blind people where they are overcoming the ‘obstacle’ of their disability rather than simply living their lives as ordinary people. Personally, what I’d like to see is stories of people with disabilities living a life where their disability is mostly just incidental to the story, much like Dr. Trask’s dwarfism was not central to his character.

One of the biggest problems compounding this is not necessarily the casting, but the clichés written into the characters they portray. This is a notorious problem with the representation of blind characters, so I can understand viewers’ trepidation at Baldwin’s Blind. How many times do we need melodramatic scenes of a blind person feeling their loved one’s face (I immediately think of Lionel Richie’s video for his song ‘Hello’ – cringe city) as the music swells in the background? We seem to only end up with stories of blind people where they are overcoming the ‘obstacle’ of their disability rather than simply living their lives as ordinary people. Personally, what I’d like to see is stories of people with disabilities living a life where their disability is mostly just incidental to the story, much like Dr. Trask’s dwarfism was not central to his character.

Self-fulfilling prophecy

While I’m not one to argue for quotas, nor do I believe that there should be any hard and fast rule about who can portray whom on film, there are undeniable issues with lack of diverse representation on-screen. Fewer roles and opportunities for diverse actors, specifically disabled actors in this instance, means fewer people with disabilities pursue acting careers and without the actors pursuing acting, there is less of a pool for casting directors to choose from. So how do we fix this? Which is the chicken, which the egg? It sadly just becomes self-perpetuating without active efforts to address this.

While I’m not one to argue for quotas, nor do I believe that there should be any hard and fast rule about who can portray whom on film, there are undeniable issues with lack of diverse representation on-screen. Fewer roles and opportunities for diverse actors, specifically disabled actors in this instance, means fewer people with disabilities pursue acting careers and without the actors pursuing acting, there is less of a pool for casting directors to choose from. So how do we fix this? Which is the chicken, which the egg? It sadly just becomes self-perpetuating without active efforts to address this.

Which is ultimately where this controversy stems from. An attempt to address the perennial under- and misrepresentation of disabled characters in our media. What we need to be wary of though is championing this cause without a sensible comprehension of the context of the industry at large and in an individual show or role. I don’t know if Alec Baldwin is the best actor for the role in Blind, but if the show depicts him with functioning vision, that potentially restricts the role from a blind actor. What is needed is a a well-rounded approach to representation because calling for wholly representative casting neither recognises nor solves the complexity of the issue. Hollywood ought to offer more characters with disabilities and that is going to involve casting able-bodied actors in some of those roles, due to acting ability or story-context in some instances. On top of that, there need to be more castings where roles not written with disabled actors in mind are open to them. In some cases, they can even make any minor edits to a script if needed given the casting choice. This is precisely what happened with Gaten Matarazzo’s cleidocranial dysotosis in Stranger Things, which causes his lisp in real life. So much of the lack of representation is down to systemic thoughtlessness rather than deliberate exclusion. We as a culture under-represent people because we don’t think about all the avenues that could be open to them. What we need are more actors and characters with disabilities in our media, but we must not let that imperative justify crass simplifications of how we need to address those issues.

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe

Pop Verse Pop Culture Universe